Évaluer et interpréter l’efficience d’utilisation des aliments et des terres par les ruminants (Full text available in English)

Il existe de nombreux indicateurs pour évaluer l’efficience d’utilisation des aliments et des terres par les ruminants. Dans cet article, nous en présentons les principaux et synthétisons de nombreux travaux qui les ont mobilisés afin d’en permettre une meilleure interprétation.

Erratum

Version du 6 octobre 2025. La figure 4 a été corrigée : sur le graphique de droite, l’intitulé de la dernière étiquette de l’axe des abscisses est « Bovin viande IR » et non « Bovin Lait IR ». La version PDF a également été mise à jour.

Toutes nos excuses pour cette regrettable erreur.

Introduction

Après la seconde guerre mondiale, des politiques agricoles ont été mises en place afin d’augmenter les productions alimentaires. Conjointement avec les évolutions de la sélection génétique, de la mécanisation et de l’utilisation des intrants, elles ont induit, notamment en Europe, une augmentation importante (de l’ordre de plus 300 %) des rendements des cultures (Mazoyer & Roudart, 2002 ; Lang & Haesman, 2015 ; FAO, 2024). Il en a résulté un excédent céréalier dans les pays occidentaux et l’introduction de produits plus riches sur le plan nutritionnel dans l'alimentation des animaux. Parallèlement à ces changements, nous avons assisté à une intensification et une spécialisation territoriale (Roguet et al., 2015) des systèmes de productions animales dont la productivité a également augmenté, de l’ordre de +130 % (FAO, 2024).

Les aliments d'origine animale, c'est-à-dire la viande, le lait et les œufs, fournissent 18 % de l’énergie et 25 % des protéines consommées par l’Homme mondialement (Mottet et al., 2017). Ils sont, entre autres, reconnus pour leur haute densité énergétique, protéique, en vitamines, notamment en vitamine B12, qui n'est pas présente dans les aliments d'origine végétale, et en micronutriments tels que le fer, le zinc et le calcium. Les qualités de ceux-ci, telles que de hautes digestibilité et biodisponibilité et la richesse en acides aminés limitants correspondent aux besoins de l’alimentation humaine (Randolph et al., 2007 ; Dror & Allen, 2011 ; Gorissen et al., 2018 ; Day et al., 2022 ; Beal & Ortenzi, 2022 ; Costa-Catala et al., 2023).

Cependant, lorsqu’il consomme des produits agricoles comestibles par l’Homme, l’élevage représente un niveau trophique supplémentaire dans l’agroécosystème entre le végétal et l’Homme, induisant des pertes inéluctables. Alors qu’à l’échelle mondiale, 86 % des aliments consommés par les animaux d’élevage sont des fourrages et des coproduits industriels, non comestibles par l’Homme (Mottet et al., 2017), il est actuellement suggéré que plus de nourriture pourrait potentiellement être produite dans certaines zones agricoles actuellement exploitées pour la production animale si elles étaient converties en systèmes de culture alternatifs donnant la priorité aux cultures comestibles par l'Homme (van Zanten et al., 2016). De ce fait, les animaux sont actuellement souvent considérés comme l'une des principales causes de l'inefficience des systèmes alimentaires (Garnett et al., 2015 ; Poore & Nemecek, 2018).

De plus, dans le contexte d’une réduction des énergies fossiles, une croissance de l’utilisation des biomasses est observée et attendue pour d’autres utilisations. Par exemple, en France, alors que 36 Mt de matière sèche (MS) sont utilisées chaque année pour les bioénergies (méthanisation, biocarburants, bois, déchets de bois), 28 Mt MS/an supplémentaires seront nécessaires d’ici 2030 (SPGE, 2024). Aussi, l’Association européenne du biogaz a pour objectif de multiplier leur production par 30 d’ici 2050 (de Groot et al., 2022).

Néanmoins, en France et en Europe, des travaux sont réalisés avec pour objectif de prioriser les différents usages de la biomasse. Le secrétariat général à la planification écologique propose une forme de merit-order, dans lequel les alimentations humaine et animale font partie des usages à considérer en priorité, alors que la production d’électricité est classée comme développement à modérer. La « Food Waste Hierarchy » communiquée par l’Union européenne favorise également l’alimentation animale à la bioénergie (European Commission, 2020).

La forte augmentation de la population humaine, 9,8 milliards en 2050, l'accroissement attendu de la demande en produits animaux de 20 % (FAO, 2023) et l'épuisement ainsi que la pollution des ressources naturelles, couplés aux effets du changement climatique (Foresight, 2011) questionnent la capacité des systèmes agricoles actuels à garantir la future sécurité alimentaire. Ainsi, cette situation suscite actuellement un regain d'intérêt de la part des communautés politiques et scientifiques, pour la contribution des productions animales à la sécurité alimentaire. Dans le cadre de la compétition entre alimentation humaine et animale, sont principalement questionnées la disponibilité en aliments et la qualité de ces derniers. Des outils doivent être définis et mobilisés pour éclairer le débat et orienter les décisions.

L’objectif de cet article de synthèse est i) de présenter des indicateurs permettant de caractériser l’efficience d’utilisation des ressources alimentaires et des surfaces par les élevages bovins, ii) de synthétiser les performances de ces élevages et iii) d'analyser la relation entre ces indicateurs et les caractéristiques de ces élevages.

1. Indicateurs pour évaluer l’utilisation des ressources alimentaires et des surfaces par les systèmes d’élevage.

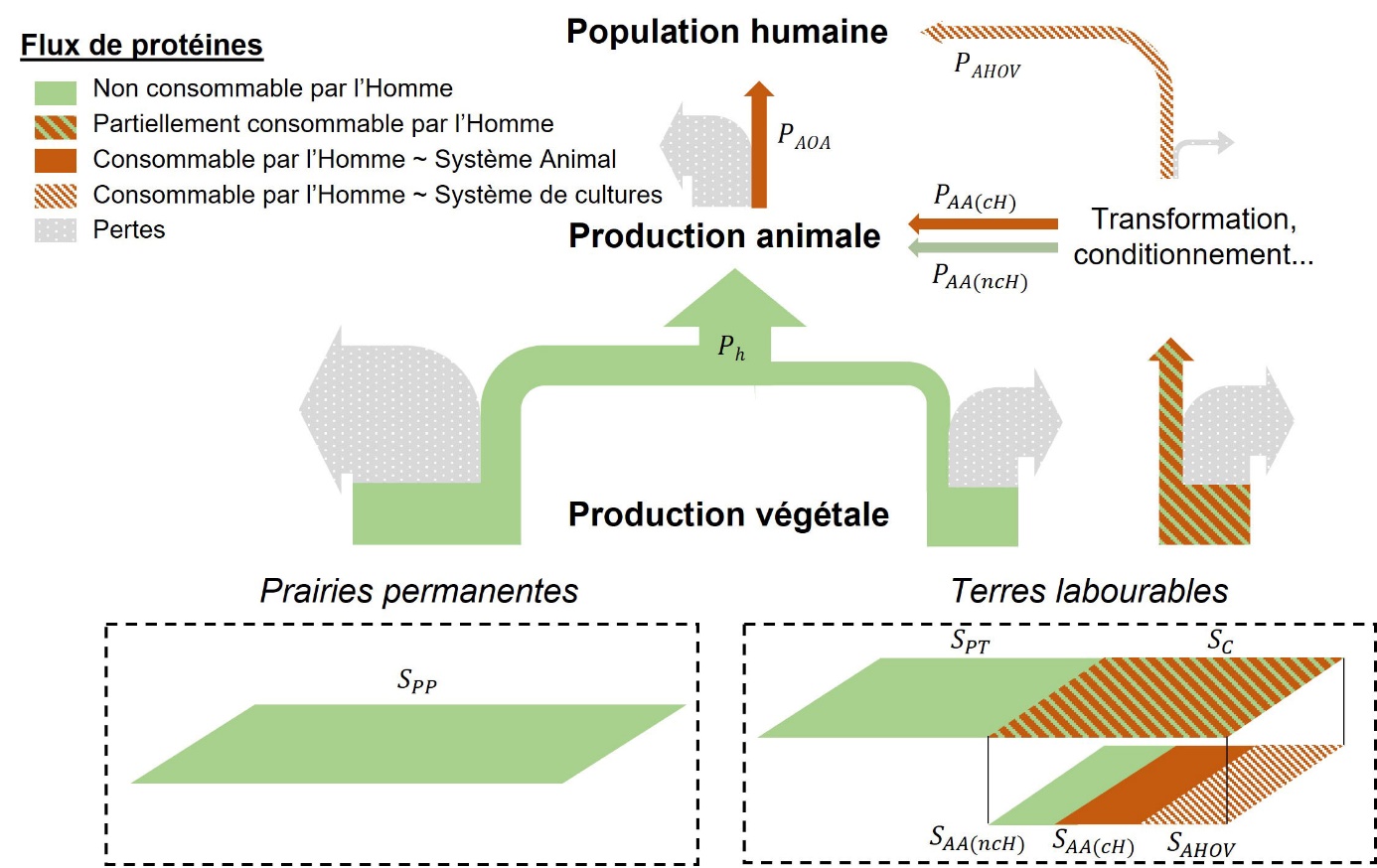

Les indicateurs présentés dans cette étude reposent sur le concept général d'efficience, soit le ratio entre une production et les ressources mobilisées pour atteindre cette production. Ils sont issus de la littérature et décrits en figure 1 et dans le tableau 1.

Ces indicateurs considèrent deux principales ressources qui limitent la production animale, les aliments pour animaux et les terres agricoles, tandis que les produits sont l’énergie et les protéines contenues dans le lait, les œufs et la viande. Les charges (ex. surfaces agricoles) utilisées en amont de la ferme, par exemple pour la production d’aliments achetés, sont également prises en compte.

Quatre types d’indicateurs ont été identifiés et sont décrits dans le tableau 1 : l’efficience nette, la productivité nette, le land use, et le land use ratio. Dans le but de synthétiser les différents résultats obtenus pour les indicateurs identifiés des bases de données ont été rassemblées. Pour chaque base de données obtenue, le type de données (ferme expérimentale, ferme commerciale, cas-type…), le nombre de systèmes étudiés, le type d’élevage, la région et les indicateurs utilisés ont été synthétisés dans le tableau 2.

Figure 1 : Flux de protéines et surfaces associées dans un agroécosystème, avec les pertes entre niveaux tropiques dues aux pertes métaboliques et différentes pertes (lors des récoltes, au stockage…).

Indicateur | Auteur, année | Équation | Caractéristiques | |

Efficience brute | Efficience de transformation exprimée en matière sèche (MS), énergie ou protéine. | |||

Efficience nette | Wilkinson et al. (2011) | Si > 1 : producteur net de protéines. Si = 1 : transformateur. Si < 1 : consommateur net. | ||

Efficience nette + Qualité des protéines | Ertl et al. (2016a) | Comme l’efficience protéique nette mais avec prise en compte de la qualité de la protéine pour l’alimentation de l’Homme (DIAAS). | ||

Land Use | De Vries et al. (2010) | Surface utilisée (m²) par unité de produit (kg MS, Joule ou kg de protéine). | ||

Labourable | Nijdam et al. (2012) | Surface labourable (m²) utilisée par unité de produit (kg MS, Joule ou kg de protéine). | ||

Prairies permanentes | Surface de prairies permanentes utilisée (m²) par unité de produit (kg MS, Joule ou kg de protéine). | |||

Land Use Ratio (LUR) | van Zanten et al. (2016) | Rapport entre une production végétale potentielle et la production animale observée à partir des mêmes sols. | ||

LUR + Part comestible des aliments et qualité des protéines | Hennessy et al. (2021) | Utilisation des parts comestibles de la production végétale potentielle et des scores DIAAS des protéines. | ||

Productivité nette | Battheu-Noirfalise et al. (2023) | Productivité des surfaces non en compétition avec l’Homme du système d’élevage. | ||

Source | N | Type de données | Type de ferme | Région | Indicateurs |

Laisse et al. (2018) | 10 | Cas-types | Bovins lait et viande, ovins viande, porcins, poulets de chair, poules pondeuses. | France | Efficience brute et nette. |

Mosnier et al. (2021) | 16 | Bovins lait et viande. | Union européenne | Efficience nette, utilisation des terres. | |

DAEA, incl. Battheu-Noirfalise et al., 2023, 2024b) | 262 | Fermes commerciales | Bovins lait et viande. | Wallonie (Belgique) | Efficience brute et nette, utilisation des terres. Productivité nette. |

Projet AUTOPROT | 213 | Bovins lait. | Belgique (Wallonie), France (Lorraine), Luxembourg, Allemagne (Rhénanie-Palatinat et Sarre) | Efficience brute et nette, utilisation des terres. Productivité nette. | |

IDELE | 142 | Bovins viande. | France | Efficience brute et nette. | |

van Zanten et al. (2016) | 123 | Bovins lait. | France | Land use ratio. | |

Hennessy et al. (2021) | 3 | Cas-types | Bovins lait, porcins. | Irlande | Land use ratio. |

Allix et al. (2024) | 12 | Bovins lait. | France | Land use ratio. | |

Rouillé et al. (2023) | 498 | Fermes commerciales | Bovins, ovins, caprins lait. | France | Efficience brute et nette. |

2. L’efficience de conversion des aliments

2.1. L’efficience brute

L’efficience brute de conversion des aliments représente la quantité d’aliments d'origine animale (AOA) produite par rapport à la quantité totale d'aliments utilisée. Celle-ci peut être calculée par kg de produit ou en prenant en compte uniquement les composantes protéiques ou énergétiques des aliments produits et consommés.

L'amélioration de l’efficience brute de conversion des aliments en masse a été un axe majeur de la recherche et du développement en production animale. Différents leviers tels que la conduite d’élevage, l’alimentation, la sélection génétique, la nutrition ou la santé animale ont été mobilisés (Garnett et al., 2015), ce qui a permis des améliorations significatives en particulier pour les volailles.

Les ruminants, et en particulier les systèmes bovins allaitants, moins standardisés que les systèmes monogastriques (Gerber et al., 2015), présentent des efficiences brutes (EB) en masse très variables. Par exemple, Wilkinson (2011) a montré que les systèmes de production de viande bovine au Royaume-Uni consomment entre 7,5 (EB = 13 %) et 27,5 kg (EB = 4 %) d'aliments par kg de viande produite, en fonction du type d’animal mais également d’aliment considéré.

Ces différences se retrouvent quand on s’intéresse à l’efficience brute énergétique. Laisse et al. (2018) ont ainsi calculé des efficiences brutes énergétiques de 25 % pour les poulets de chair, 26 % pour le porc et seulement 4 % pour le bœuf. La différence entre les poulets de chair et les autres productions de viande s'accroît quand on considère la fraction protéique des aliments. En effet, l'efficience brute protéique atteint 54 % pour les poulets de chair, contre 40-42 % pour le porc et 8 % pour le bœuf. Cela peut conduire à l'idée simpliste que le remplacement de toute la viande de bœuf par de la viande de volaille permettrait de nourrir davantage de personnes. Aux États-Unis, cela représenterait 116 millions de personnes supplémentaires nourries (Shepon et al., 2016).

L’efficience brute de conversion de l'alimentation en protéines atteint 27 % pour les systèmes de poules pondeuses et 19-24 % pour les systèmes de vaches laitières (Laisse et al., 2018).

2.2. L’efficience nette

Par rapport aux monogastriques qui présentent uniquement une digestion enzymatique, les ruminants ont la capacité de mieux valoriser l'herbe et d'autres aliments riches en fibres non comestibles par l’Homme grâce à la prédigestion microbienne spécifique qui s’opère dans leur rumen. La première apparition d'une efficience de conversion des aliments « comestibles par l'Homme » est proposée par Steinfeld et al. (1997), qui estime qu'au niveau mondial, les animaux utilisent 1,4 fois plus d'aliments comestibles par l'Homme que la quantité d'AOA qu'ils produisent. Wilkinson (2011) formalise l'indicateur de « ratio de conversion des aliments comestibles » et décrit les performances d'une diversité de productions animales au Royaume-Uni. L'efficience nette de conversion des aliments est proposée ultérieurement (Ertl et al., 2015 ; Laisse et al., 2018) et est utilisée dans le présent article. Elle représente l’inverse de l’indicateur présenté par Wilkinson (2011), la quantité d’AOA produite est divisée par la quantité d'aliments comestibles par l'Homme utilisée.

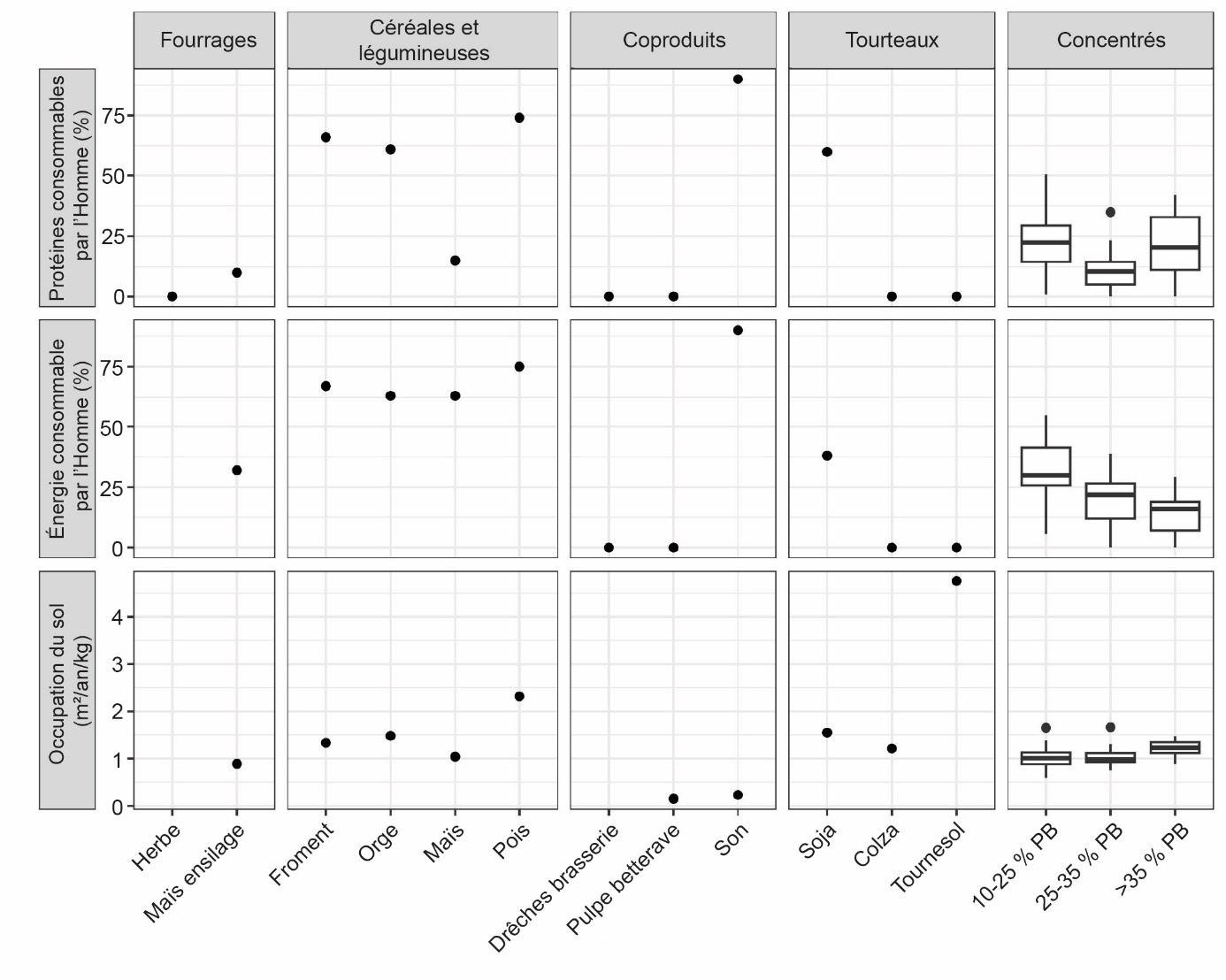

Pour calculer ce ratio, la fraction comestible par l'Homme de chaque aliment est estimée comme étant la proportion du produit qui peut actuellement être valorisée en tant qu'aliment pour l'Homme (figure 2). Étant donné que les cultures alimentaires sont séparées en différentes fractions (par exemple, les grains de blé moulus sont séparés en farine, en son de blé et en gluten), les quantités de protéines et d’énergie directement comestibles par l'Homme représentent les proportions pondérées de protéines et d'énergie qui se trouvent dans chacune des fractions comestibles par l'Homme (figure 2). Pour de nombreux aliments pour animaux, les fractions énergétiques et protéiques comestibles par l'Homme sont très similaires. Toutefois, certains d'entre eux présentent des différences plus importantes. Par exemple, le maïs est en grande partie valorisé pour son amidon, tandis que les sous-produits riches en protéines (corn gluten feed et corn gluten meal) ne sont actuellement pas comestibles par l'Homme (Laisse et al., 2018).

Figure 2 : Proportions de protéines et d'énergie et utilisation des terres pour différents aliments pour bétail, sur base de Laisse et al. (2018) et de la base de données ECOALIM pour l’occupation du sol, pour les aliments de base et 203 recettes de concentrés (Projet AUTOPROT).

Sur cette base, dans le cadre du projet Interreg AUTOPROT (037-4-09-092), 210 formules de concentrés commercialisées en Wallonie (Belgique), Lorraine (France), Luxembourg, Rhénanie-Palatinat et en Sarre (Allemagne) ont été étudiées. La part de protéines en compétition avec l’Homme dans les concentrés avec une teneur inférieure à 25 % de protéines dépend principalement de la proportion de céréales. Pour les concentrés à haute teneur en protéines, la part de tourteau de colza, qui n’est pas considérée en compétition, et celle de tourteau de soja dans l’aliment concentré expliquent la variabilité observée (figure 2).

Pour des systèmes d’élevage de type français, l’estimation de l'efficience protéique nette était supérieure à un pour les systèmes bovins laitiers (1,01-2,57), le porc et les poules pondeuses (1,02), c’est-à-dire qu’ils produisent plus de protéines consommables par l’Homme qu’ils n’en consomment, alors qu’elle était inférieure à un pour les systèmes bovins viande (0,67-0,71) et les poulets de chair (0,88) (Laisse et al., 2018). Les ovins viande ont affiché des performances supérieures (1,28) ou inférieures (0,34) en fonction du système de production. L'estimation de l’efficience énergétique nette était systématiquement plus faible et seuls les systèmes laitiers extensifs à l’herbe affichaient une valeur supérieure à un (Laisse et al., 2018). En termes de systèmes laitiers, les bovins montrent des performances moyennes supérieures aux brebis et chèvres (Rouillé et al., 2023). En analysant les systèmes bovins viande européens, Mosnier et al. (2021) ont également souligné l'importance de prendre en compte les différentes phases de la vie des animaux de boucherie. En effet, les systèmes naisseurs qui utilisent beaucoup d’herbe présentent généralement une efficience nette élevée, tandis que les engraisseurs peuvent afficher des performances plus faibles en raison d'une utilisation plus importante d'aliments en compétition avec l’Homme, tels que les céréales. Les systèmes naisseurs doivent donc être combinés avec des systèmes d’engraissement, ce qui les rend consommateurs nets de protéines végétales consommables par l’homme dans la plupart des cas (Mosnier et al., 2021).

Par ailleurs, la fraction comestible par l'Homme des aliments pour animaux n'est ni fixe ni généralisable car elle dépend du contexte et des technologies disponibles dans le secteur agroalimentaire du pays en question (Laisse et al., 2018). Par exemple, Ertl et al. (2015) considèrent que 30 % des protéines présentes dans le tourteau de colza peuvent être extraites et valorisées en alimentation humaine. Cependant, Laisse et al. (2018) considèrent que la fraction protéique du colza comestible par l'Homme est nulle car ce procédé d’extraction n’est pas mis en œuvre en France. Ils décrivent différents scénarios en termes de fraction comestible pour l'Homme des aliments pour animaux. En effet, dans le futur, des taux d'extraction élevés dus à de nouveaux procédés technologiques et à des changements dans les habitudes de consommation pourraient conduire à des fractions comestibles plus élevées (Ertl et al., 2015). Avec ces scénarios, Laisse et al. (2018) ont constaté une réduction de l'efficacité protéique nette de 16 à 40 % pour les ruminants et de 36 à 51 % pour les monogastriques.

2.3. Le rôle de la qualité des protéines

Afin de représenter la différence de qualité et de digestibilité des protéines, le score de digestibilité des acides aminés indispensables (DIAAS) a été proposé par la FAO (2013) comme méthode de référence. Ce score représente la teneur du premier acide aminé indispensable limitant dans la protéine testée par rapport à la teneur du même acide aminé dans une protéine de référence qui correspond aux besoins d’un enfant de six mois à trois ans et est basé sur la digestibilité iléale réelle des acides aminés indispensables (Rutherfurd et al., 2015).

Initialement, il était suggéré de tronquer les valeurs de DIAAS à 100 % car les valeurs supérieures représentent un surplus par rapport aux besoins nutritionnels humains et ne sont donc pas valorisées par le corps humain si l’aliment constitue le seul composant de l’assiette (FAO & WHO, 1991). Ultérieurement, il a été argumenté de considérer les valeurs non tronquées car, dans les régimes mixtes, un aliment à base de protéines de haute qualité peut compléter un autre aliment déficitaire en acides aminés indispensables (Rutherfurd et al., 2015). La FAO (2013) suggère d'utiliser les besoins en acides aminés pour un enfant de six mois à trois ans comme protéine de référence. La prise en compte du DIAAS dans le calcul de l'efficience nette multiplie les valeurs de l'efficacité nette de 1,7 à 2,4 pour la production de lait, de 1,6 pour la production d'œufs et de 1,4 à 1,9 pour la production de viande (Ertl et al., 2016a, 2016b ; Laisse et al., 2018).

Les efficiences obtenues dans les différentes sources, selon les différentes variantes présentées ci-dessus sont synthétisées en figure 3. La figure 3B représente l’efficience nette de systèmes avec un double troupeau bovin, en fonction de la proportion de vaches allaitantes et laitières. Les efficiences protéiques nettes pour les différents types d’élevages bovins viande (figure 3C) et lait (figure 3D) sont également illustrées.

Figure 3 : Efficiences brutes et nettes de conversion des protéines et de l’énergie des aliments pour différents types de fermes bovines (Source : Projets ERADAL et AUTOPROT).

3. Utilisation des surfaces

La disponibilité en terres agricoles, et en particulier en terres labourables, est considérée comme le facteur le plus limitant pour nourrir la planète en 2050 (Bruinsma, 2009). L'utilisation totale des terres représente l’ensemble des surfaces agricoles utilisées (sur et en dehors de l’exploitation) par unité de produits animaux (p. ex. par kg de protéine produite).

Dans une revue de 16 études d'analyse du cycle de vie (ACV), De Vries et De Boer (2010) ont mis en évidence des surfaces nécessaires pour la production de produits animaux allant de 1,1 à 2,0 m²/kg pour le lait, 4,5 à 6,2 m²/kg pour les œufs, 8,1 à 9,9 m²/kg pour la viande de poulet, 8,9 à 12,1 m²/kg pour la viande de porc et enfin de 27 à 491 m²/kg pour la viande de bœuf. Cependant, toutes les terres n'ont pas la même valeur agricole. En particulier, il existe une forte différence entre la valorisation potentielle des prairies permanentes et celle des terres labourables (Wirsenius, 2003). Dans une autre étude, Nijdam et al. (2012) ont calculé la part des prairies et ont montré que, bien que la production de viande de bœuf provenant de systèmes pastoraux extensifs affiche l'utilisation de terres la plus élevée, celles-ci peuvent être entièrement composées de prairies permanentes.

Historiquement, les prairies permanentes correspondaient aux terres non labourables, aux sols superficiels et/ou à forte teneur en pierres, aux parcelles peu accessibles et/ou très pentues. Cependant, avec la spécialisation des systèmes de production et des territoires, certaines terres cultivables ont été transformées en prairies qui sont devenues permanentes. On estime aujourd'hui, sur la base des conditions pédoclimatiques, que certaines prairies permanentes pourraient être cultivées (IIASA/FAO, 2012). Plus précisément, Mottet et al. (2017) ont estimé qu'à l'échelle mondiale, 35 % des deux milliards d'hectares de prairies utilisés par le bétail pourraient être convertis en terres cultivées. Toutefois, ce changement d'utilisation des terres pourrait entraîner des émissions de GES en libérant le carbone stocké dans le sol, des pertes de biodiversité et d'autres services écosystémiques (Foley et al., 2005).

3.1. Land use ratio

Les indicateurs d’utilisation des terres, totales, labourables ou de prairies permanentes donnent une idée de l'efficience de l'utilisation des terres pour différentes productions animales. Toutefois, il n'est pas certain que les terres labourables utilisées par les animaux puissent produire plus d'aliments sur la base d’une rotation optimisant la présence de cultures consommables par l’Homme, que la production actuelle d’AOA.

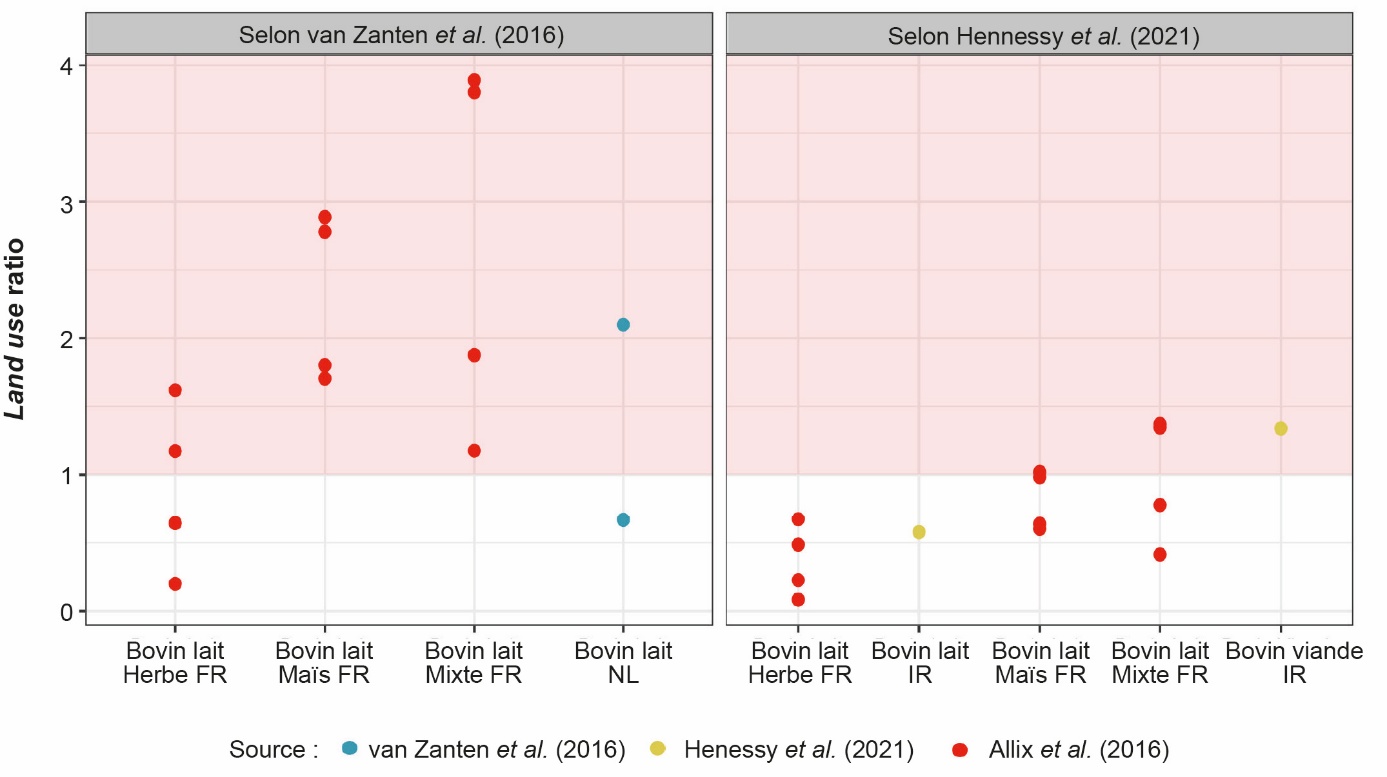

Pour répondre à cette question, van Zanten et al. (2016) ont proposé le land use ratio (LUR), qui compare le potentiel de production de protéines végétales sur les terres utilisées par l’élevage aux productions protéiques par l’élevage. Les prairies sur sol sablonneux sont considérées comme cultivables avec un potentiel de production de 56 t/ha de pommes de terre ou 7,3 t/ha de froment. Deux systèmes d'élevage aux Pays-Bas, un en poules pondeuses et l’autre en vaches laitières sur sol sablonneux, présentaient un LUR supérieur à un, indiquant qu’un système de culture produirait plus de protéines par unité de surface que les systèmes d’élevage actuellement en place. Le système laitier sur sol tourbeux, moins propice aux cultures, présentait, quant à lui, un LUR inférieur à un.

Hennessy et al. (2021) ont proposé un LUR basé sur les protéines comestibles multipliées par le score DIAAS pour les systèmes d'élevage de bovins laitiers, de bovins allaitants et de porcs en Irlande. Ils ont modélisé l'influence de la part de prairies permanentes cultivables sur leur résultat. Sur cette base, lorsque la part de prairies cultivables passe de 0 à 100 %, le LUR passe de 0,25 à 1,35 pour les systèmes bovins laitiers et de 0,28 à 3,77 pour les systèmes bovins allaitants. Les systèmes porcins ne seraient que légèrement affectés en raison de leur faible utilisation des prairies. Ils illustrent également l'importance de la rotation des cultures utilisée pour la comparaison. En effet, en utilisant une rotation de cultures riches en protéines (céréales, protéagineux), le LUR sera plus élevé qu’en utilisant des cultures pauvres en protéines (pommes de terre, betteraves sucrières). Le potentiel offert par des systèmes de cultures est également associé à de fortes incertitudes quant à sa viabilité à long terme (par exemple, maintien de la fertilité des sols, lutte contre les ravageurs) et à la variabilité des rendements escomptés en fonction du contexte biophysique et des systèmes de gestion des exploitations.

Allix et al., (2024) ont calculé le LUR selon les deux méthodes pour 12 systèmes laitiers français (quatre herbagers, quatre mixtes et quatre maïs). Comme illustré à la figure 4, le LUR obtenu est inférieur pour les systèmes herbagers et généralement supérieur avec la méthode de van Zanten et al. (2016). Cette étude, qui, contrairement aux deux études précédentes, considère que les prairies permanentes sont non cultivables, montre néanmoins que le résultat dépend fortement des hypothèses posées, notamment sur le potentiel des terres utilisées par les ruminants en termes de productions végétales et sur la prise en compte ou non des différences de qualité nutritionnelle des produits animaux et végétaux.

3.2. Productivité nette

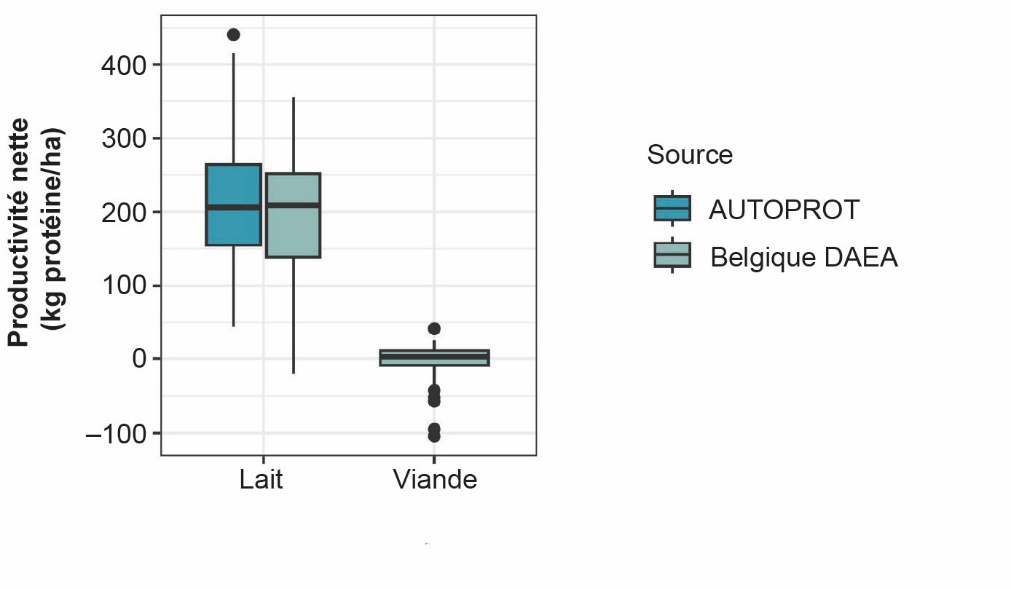

La productivité nette a été proposée pour représenter plus précisément la contribution des systèmes d’élevage à la disponibilité en aliment en intégrant l’utilisation d’aliments en compétition avec l’alimentation humaine et l’utilisation des terres agricoles (Battheu-Noirfalise et al., 2023). Cet indicateur est égal à la différence entre la quantité d’AOA produite et les aliments en compétition avec l’alimentation humaine utilisés, divisée par les surfaces utilisées par l’élevage ne permettant pas de produire des aliments comestibles par l’Homme. Cette surface « non comestible » correspond à l’ensemble des prairies permanentes et à la part des terres labourables associée aux fractions (coproduits) des cultures non valorisables par l’Homme. La valeur de productivité nette est positive lorsque le système est producteur de protéines consommables par l’Homme et négative sinon. Les systèmes laitiers obtiennent une productivité nette positive avec environ 200 kg de protéines produites par ha non consommables par l’Homme. Les systèmes bovins viandes obtiennent une productivité située autour de zéro (figure 5). Battheu-Noirfalise et al. (2024b) observe de –8 kg protéines/ha pour les systèmes basés sur le maïs et de l’intraconsommation à 22 kg protéines/ha pour les systèmes basés sur l’herbe.

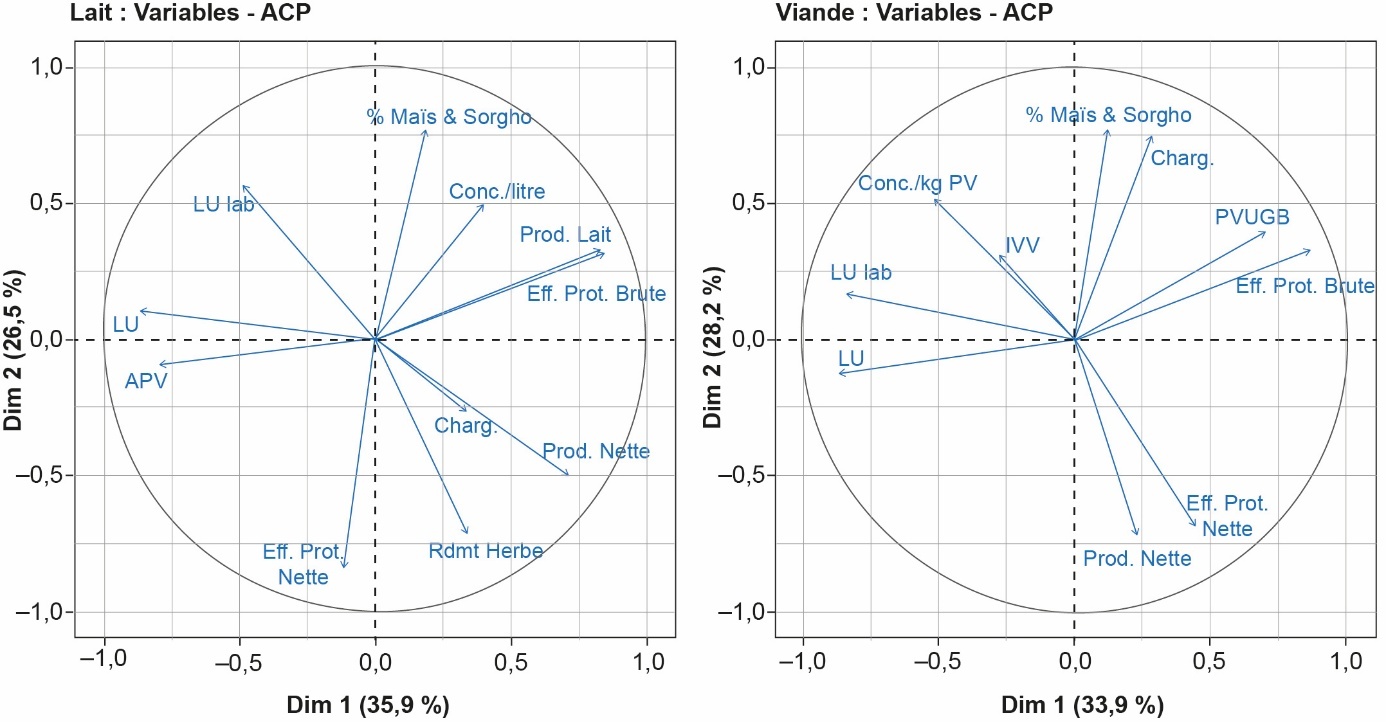

Figure 6 : Analyse en composantes principales réalisée sur les performances techniques d’exploitations laitières à gauche (sources données : DAEA et AUTOPROT) ou d’exploitations allaitantes à droite (sources données : DAEA).

4. Performances et paramètres techniques des élevages

Dans le but de mieux comprendre la variabilité des performances observées, une synthèse des corrélations entre des paramètres de gestion et les indicateurs d’efficience, d’utilisation des terres et de productivité, calculées séparément pour les différentes bases de données mobilisées, est présentée dans le tableau 3. Les graphiques des variables résultants de l’analyse en composantes principales sont présentés en figure 6. Les efficiences brutes (protéiques et énergétiques) sont fortement corrélées à la productivité par vache pour les élevages laitiers et au gain de poids par UGB pour les élevages viande, et donc, dans les deux cas à la part de maïs dans la ration. L’efficience brute est également corrélée négativement à l’âge au premier vêlage et à l’intervalle vêlage-vêlage. En effet, plus l’âge au premier vêlage est faible et plus l’intervalle vêlage-vêlage est court, moins les périodes improductives, et donc inefficientes, des animaux sont importantes. Les efficiences nettes (protéiques et énergétiques) sont négativement corrélées à l’utilisation de concentrés (par litre ou par kg de poids vif) et à la part de maïs dans la ration, et positivement corrélées à la part de pâturage pour les exploitations laitières. Ces observations étayent les observations réalisées par Laisse et al. (2018), avec un système bovin lait herbager moins productif mais présentant une efficience nette plus élevée que le système laitier basé sur le maïs.

L’utilisation des terres, pour lesquelles on vise un score bas et donc des corrélations à interpréter de manière opposée, est corrélée à l’âge au premier vêlage et corrélée négativement à la productivité laitière et de viande. L’utilisation des terres labourables, en revanche, est corrélée positivement à l’utilisation de maïs et de concentrés.

La productivité nette est corrélée positivement à la productivité laitière et au rendement en herbe, et corrélée négativement à l’âge au premier vêlage et à l’utilisation de maïs et, pour les élevages viande, de concentrés. Battheu-Noirfalise et al. (2023) ont également observé une corrélation avec la teneur en protéines des concentrés utilisés dans les systèmes laitiers.

Pour les exploitations laitières, la productivité nette est corrélée négativement avec l’utilisation des terres arables et corrélée avec l’efficience nette, comme observé par Battheu-Noirfalise et al. (2023). Pour les fermes allaitantes, la productivité nette est fortement corrélée avec l’efficience nette et ces deux variables sont corrélées négativement avec l’utilisation des terres arables.

Bovins lait | Bovins viande | |||||||||||

Concentrés (kg/litre de lait) | Production laitière par vache par an | Âge au premier vêlage | Chargement | % Maïs dans les fourrages | % Pâturage | Production d'herbe (kg/ha) | Intervalle vêlage–vêlage | Poids vif produit par UGB | Chargement | Concentrés (kg/kg PV) | % Maïs dans les fourrages | |

Efficience protéique brute | – | + + + | – – | 0 | + + | – – | 0 | – – – | + + + | + | + | + + |

Efficience énergétique brute | 0 | + + + | – – | + | + + | – – | – – | + + | + | + | + + | |

Efficience protéique nette | – – | – | + | 0 | – – | + + | + | – | 0 | – | – – | – |

Efficience nette | – | – – | + | – – | – – – | + + + | 0 | – | 0 | – – – | – – | |

Land use (kg protéines/m²) | – | – – | + + | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | – | + | – | |

Land use terres labourables | + | – | + | 0 | + + | – | 0 | – | 0 | + + | 0 | |

Productivité nette | 0 | + + | – – | + | – | + + | – | 0 | – | – – | – – | |

5. Indicateurs, interprétations et perspectives

L’interprétation d’indicateurs tels que l’efficience nette peut être simple. Dans ce cas, on considère qu’un système d’élevage est producteur net de protéines s’il a une efficience supérieure à un. Néanmoins, cet indicateur ne renseigne que partiellement sur les performances du système. Ainsi, avoir une efficience fortement supérieure à un n’implique pas toujours une meilleure contribution à la sécurité alimentaire qu’une valeur plus faible car cet indicateur n’intègre pas le niveau de production de l’élevage par unité de surface, qui peut être très faible. L’indicateur de productivité nette, prenant en compte la production et les surfaces utilisées ne souffre pas de ce défaut, une productivité nette de 300 kg de protéines par hectare non en compétition avec l’Homme, contribuera, par construction, plus à la production de protéines pour l’Homme qu’une ferme qui produit 100 kg de protéines par hectare. Les niveaux atteints de cet indicateur doivent également toutefois être relativisés. En effet, le contexte pédoclimatique détermine largement le potentiel de production et selon la mise en œuvre (élément de comparaison), il ne renseigne pas nécessairement sur les marges de progression des systèmes. En comparant à une production végétale optimale, le LUR, prend, théoriquement, mieux en compte les marges de progression que les autres indicateurs. Cependant, les hypothèses de rendement utilisées dans le calcul du LUR restent théoriques. Pour le LUR, le fait de comparer des systèmes à un optimum végétal pose également question. N’y aurait-il pas un autre optimum que le tout végétal ? Qu’en est-il d’alternatives animales ou même de systèmes en polyculture-élevage visant à optimiser les synergies animal-végétal qui maximiseraient la production d’alimentation à destination de l’Homme sur les mêmes surfaces ?

Les indicateurs décrits dans cette contribution ont pour objectif de quantifier l’efficience et des niveaux de productions atteints sur la base des ressources végétales et des sols. Toutefois de nombreux autres critères doivent actuellement être pris en compte pour répondre aux enjeux actuels tels que les impacts et/ou services environnementaux ou encore les performances économiques et sociales. En particulier, les émissions de méthane sont une autre critique importante faite à l’égard des élevages de ruminants. Des solutions doivent donc être trouvées pour combiner production alimentaire et réduction des émissions de gaz à effet de serres (GES). Ineichen et al. (2024) proposent de combiner la production nette et les émissions de GES dans un seul indicateur. Pour 87 fermes suisses, la production nette de protéines par kg éqCO2 s’élève en moyenne à 16,8 g protéines brutes/kg éqCO2 et est fortement corrélée négativement à l’utilisation de concentrés.

Par ailleurs, sur base de modélisations, Mertens et al. (2023) et Kearney et al. (2022) évaluent des indicateurs de durabilité, incluant la rentabilité, les émissions de méthane et l’efficience nette de la production de viande à partir de veaux laitiers, montrant l’intérêt de ces systèmes d’un point de vue environnemental et les compromis à trouver entre rentabilité et utilisation des terres arables.

Cependant une convergence des différents indicateurs vers des valeurs favorables aux différents critères de la durabilité n’est pas assurée et des compromis doivent certainement être trouvés afin de définir des pistes d’évolution à mettre en œuvre. Un tel exercice a déjà été mené avec un panel multi-acteurs à l’aide d’un outil d’aide à la décision (Battheu-Noirfalise et al., 2024a) pour des systèmes laitiers.

Conclusion

Cette synthèse rassemble les nombreux indicateurs et des jeux de données conséquents permettant de caractériser les systèmes d’élevage de ruminants actuels et leur capacité à être producteurs nets d’aliments à destination de l’Homme. Les performances des systèmes sont analysées en fonction du type d’élevage, de leur assolement et des paramètres de gestion. L’étude démontre des marges d’amélioration notamment en basant l’élevage sur l’herbe et en réduisant l’utilisation de maïs et de concentré. Cette synthèse centrée sur la France et quelques pays limitrophes, ainsi que d'autres articles internationaux, démontre l'intérêt des systèmes d'élevage de ruminants pour valoriser les biomasses non comestibles par l’Homme. Dans un futur, où la demande en aliments est vouée à augmenter et l’éventualité de la mobilisation potentielle des ressources végétales vers d’autres fins (p. ex. énergie, fibres…), les questions primordiales qui touchent les ruminants seront centrées sur l'optimisation de l’utilisation des aliments non consommables par l’Homme et des surfaces non cultivables, sans oublier les autres services rendus par l’élevage. Ceci nécessite de repenser la place et les pratiques optimales d'élevage dans les agroécosystèmes.

Contributions des auteurs

Alexandre Mertens : conceptualisation, curation des données, visualisation, rédaction - version originelle ; Caroline Battheu-Noirfalise : conceptualisation, ressources, validation, rédaction - version originelle ; Pauline Madrange : rédaction - révision et correction ; Michaël Mathot : conceptualisation, rédaction - révision et correction ; Alice Berchoux : ressources ; René Baumont : conceptualisation, ressources, rédaction - révision et correction.

Remerciements

Les auteurs remercient les partenaires des projets AUTOPROT, Sustainbeef et ERADAL, du GIS Élevage demain et Avenir Élevage et des réseaux d’élevage Inosys pour le partage des données. Cette recherche est partiellement financée par le Fonds pour la formation à la recherche dans l'industrie et dans l'agriculture (FRIA).

Notes

- 1. Cet article a fait l'objet d'une présentation aux 27e journées Rencontres autour des Recherches sur les Ruminants, les 4-5 décembre 2024 à Paris (Mertens et al., 2024)

Références

- Allix, M., Rouillé, B., & Baumont, R. (2024). Land-use efficiency of grass-based versus maize-based dairy cattle to protein production in France. In C.W. Klootwijk, M. Bruinenberg, M. Cougnon, N.J. Hoekstra, R. Ripoll-Bosch, S. Schelfhout, R.L.M. Schils, T. Vanden Nest, N. van Eekeren, W. Voskamp-Harkema & A. van den Pol-van Dasselaar (Eds.), Grassland Science in Europe Vol. 29 – Why grasslands? (pp. 46-48). Proceedings of the 30th General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation. https://www.europeangrassland.org/fileadmin/documents/Infos/Printed_Matter/Proceedings/EGF2024.pdf

- Battheu-Noirfalise, C., Mertens, A., Froidmont, E., Mathot, M., Rouillé, B., & Stilmant, D. (2023). Net productivity, a new metric to evaluate the contribution to food security of livestock systems: the case of specialised dairy farms. Agronomy for Sustainable. Development, 43, 54. doi:10.1007/s13593-023-00901-z

- Battheu-Noirfalise, C., Mertens, A., Faivre, A., Charles C., Dogot, T., Stilmant, D., Beckers, Y., & Froidmont E. (2024a). Classifying and explaining Walloon dairy farms in terms of sustainable food security using a multiple criteria decision making method. Agricultural Systems, 221, 104112. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2024.104112

- Battheu-Noirfalise, C., Mertens, A., Soyeurt, H., Stilmant, D., Froidmont, E., & Beckers, Y. (2024b). Influence of crop-livestock integration on direct and indirect contributions of beef systems to food security. Agricultural Systems, 220, 104067. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2024.104067

- Beal, T. & Ortenzi, F. (2022). Priority micronutrient density in foods. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.806566

- Bruinsma, J. (2009). The resource outlook to 2050: By how much do land, water and crop yields need to increase by 2050? (Expert meeting on how to feed the world in 2050). FAO. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/07929068-7a29-45c4-ae00-ed416774ca0b/content

- Costa-Catala, J., Toro-Funes, N., Comas-Basté, O., Hernández-Macias, S., Sánchez-Pérez, S., Latorre-Moratalla, M. L., Veciana-Nogués, M. T., Castell-Garralda, V., & Vidal-Carou, M. C. (2023). Comparative assessment of the nutritional profile of meat products and their plant-based analogues. Nutrients, 15(12), 2807. doi:10.3390/nu15122807

- Day, L., Cakebread, J. A. & Loveday, S. M. (2022). Food proteins from animals and plants: Differences in the nutritional and functional properties. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 119, 428-442. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.12.020

- de Groot, S., Kersjes, J., Natonek, V., Roefs, B., & Scavizzi, S. (2022). The growing competition between the bioenergy industry and the feed industry (Technical report). Wageningen University & Research. https://fefac.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/22_DOC_106.pdf

- de Vries, M., & de Boer, I. J. M. (2010). Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. Livestock Science, 128, 1-11. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2009.11.007

- Dror, D. K., & Allen, L. H. (2011). The Importance of milk and other animal-source foods for children in low-income countries. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 32(3), 227-243. doi:10.1177/156482651103200307

- Ertl, P., Klocker, H., Hörtenhuber, S., Knaus, W., & Zollitsch, W. (2015). The net contribution of dairy production to human food supply: The case of Austrian dairy farms. Agricultural Systems, 137, 119-125. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2015.04.004

- Ertl, P., Knaus, W., & Zollitsch, W. (2016a). An approach to including protein quality when assessing the net contribution of livestock to human food supply. Animal, 10(11), 1883-1889. doi:10.1017/S1751731116000902

- Ertl, P., Steinwidder, A., Schönauer, M., Krimberger, K., Knaus, W., & Zollitsch, W. (2016b). Net food production of different livestock: A national analysis for Austria including relative occupation of different land categories. Die Bodenkultur: Journal of Land Management, Food and Environment, 67(2), 91-103. https://doi.org/10.1515/boku-2016-0009

- European Commission. (2020). Brief on food waste in the European Union (Technical report). European Commission. https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/publication/brief-food-waste-european-union_en

- FAO. (2013). Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition: Report of an FAO Expert Consultation (Food and nutrition paper 92). FAO. https://www.fao.org/ag/humannutrition/35978-02317b979a686a57aa4593304ffc17f06.pdf

- FAO. (2023). Pathways towards lower emissions – A global assessment of the greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation options from livestock agrifood systems. FAO. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/b3f21d6d-bd6d-4e66-b8ca-63ce376560b5

- FAO. (2024). FAOSTAT. Consulted on 2024-04-26 at https://www.fao.org/faostat/fr/?data/QC/visualize#data/QCL/visualize

- FAO. & WHO. (1991). Protein quality evaluation: Report of the joint FAO/WHO expert consultation (Food and nutrition paper 51). FAO. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/t0501e

- Foley, J. A., DeFries, R., Asner, G. P., Barford, C., Bonan, G., Carpenter, S. R., Chapin, F. S., Coe, M. T., Daily, G. C., Gibbs, H. K., Helkowski, J. H., Holloway, T., Howard, E. A., Kucharik, C. J., Monfreda, C., Patz, J. A., Prentice, I. C., Ramankutty, N., & Snyder, P. (2005). Global consequences of land use. Science, 309(5734), 570-574. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1111772

- Foresight. (2011). Future of Food and Farming: Final Project Report. The Government Office for Science. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/future-of-food-and-farming

- Garnett, T., Röös, E., & Little, D. (2015). Lean, green, mean, obscene…? What is efficiency? And is it sustainable? Food Climate Research Network, University of Oxford. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.4733.2323

- Gerber, P. J., Mottet, A., Opio, C. I., Falcucci, A., & Teillard, F. (2015). Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Science, 109, 2-12. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.05.013

- Gorissen, S. H. M., Crombag, J. J. R., Senden, J. M. G., Waterval, W. A. H., Bierau, J., Verdijk, L. B., & van Loon, L. J. C. (2018). Protein content and amino acid composition of commercially available plant-based protein isolates. Amino Acids, 50, 1685-1695. doi:10.1007/s00726-018-2640-5

- Hennessy, D. P., Shalloo, L., van Zanten, H. H. E., Schop, M., &De Boer, I. J. M. (2021). The net contribution of livestock to the supply of human edible protein: the case of Ireland. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 159(5‑6), 463-471. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859621000642

- IIASA/FAO. (2012). Global agro-ecological zones (GAEZ ver 3.0). https://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/13290/1/GAEZ_Model_Documentation.pdf

- Ineichen, S., Elmiger, N., Flachsmann, T., Grenz, J., & Reidy, B. (2024). Greenhouse gas emissions and feed-food competition on Swiss dairy farms, In C.W. Klootwijk, M. Bruinenberg, M. Cougnon, N.J. Hoekstra, R. Ripoll-Bosch, S. Schelfhout, R.L.M. Schils, T. Vanden Nest, N. van Eekeren, W. Voskamp-Harkema & A. van den Pol-van Dasselaar (Eds.), Grassland Science in Europe Vol. 29 – Why grasslands? (pp. 52-54). Proceedings of the 30th General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation. https://www.europeangrassland.org/fileadmin/documents/Infos/Printed_Matter/Proceedings/EGF2024.pdf

- Kearney, M., O’Riordan, E. G., McGee, M., Breen, J., & Crosson, P. (2022). Farm-level modelling of bioeconomic, greenhouse gas emissions and feed-food performance of pasture-based dairy-beef systems, Agricultural Systems, 203, 103530, https://doi.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103530

- Laisse, S., Baumont, R., Dusart, L., Gaudré, D., Rouillé, B., Benoit, M., Veysset, P., Rémond, D., & Peyraud, J. -L. (2018). L’efficience nette de conversion des aliments par les animaux d’élevage : une nouvelle approche pour évaluer la contribution de l’élevage à l’alimentation humaine. INRA Productions Animales. 31, 269-288. doi:10.20870/productions-animales.2018.31.3.2355

- Lang, T., & Haesman, M. (2015). Food Wars: the global battle for mouths, minds and markets (2e éd.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315754116

- Mazoyer, M., & Roudart, L. (2002). Histoire des agricultures du monde : du néolithique à la crise contemporaine (Nouvelle édition). Éditions du Seuil.

- Mertens, A., Kokemohr, L., Braun, E., Legein, L., Mosnier, C., Pirlo, G., Veysset, P., Hennart, S., Mathot, M., & Stilmant, D. (2023). Exploring rotational grazing and crossbreeding as options for beef production to reduce GHG emissions and feed-food competition through farm-level bio-economic modeling. Animals, 13(6), 1020. doi:10.3390/ani13061020

- Mertens, A., Battheu-Noirfalise, C., Madrange, P, Mathot, M., Berchoux, A., Baumont, R. (2024). Évaluer et interpréter l’efficience d’utilisation des aliments et des terres par les ruminants [Conférence]. 27e Rencontres autour des Recherches sur les Ruminants, Paris.

- Mosnier, C., Jarousse, A., Madrange, P., Balouzat, J., Guillier, M., Pirlo, G., Mertens, A., ORiordan, E., Pahmeyer, C., Hennart, S., Legein, L., Crosson, P., Kearney, M., Dimon, P., Bertozzi, C., Reding, E., Iacurto, M., Breen, J., Carè, S., & Veysset, P. (2021). Evaluation of the contribution of 16 European beef production systems to food security. Agricultural Systems, 190, 103088. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103088

- Mottet, A., de Haan, C., Falcucci, A., Tempio, G., Opio, C., & Gerber, P. (2017). Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Global Food Security, 14, 1-8. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.001

- Nijdam, D., Rood, T., & Westhoek, H. (2012). The price of protein: review of land use and carbon footprints from life cycle assessments of animal food products and their substitutes. Food Policy, 37(6), 760-770. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.08.002

- Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216

- Randolph, T. F., Schelling, E., Grace, D., Nicholson, C. F., Leroy, J. L., Cole, D. C., Demment, M. W., Omore, A., Zinsstag, J., & Ruel, M. (2007). Invited Review: Role of livestock in human nutrition and health for poverty reduction in developing countries. Journal of Animal Science, 85(11), 2788-2800. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0467

- Roguet, C., Gaigné, C., Chatellier, V., Cariou, S., Carlier, M., Chenu, R., Daniel, K., & Perrot, C. (2015). Spécialisation territoriale et concentration des productions animales européennes : état des lieux et facteurs explicatifs. INRA Productions Animales, 28(1), 5-22. https://doi.org/10.20870/productions-animales.2015.28.1.3007

- Rouillé, B., Jost, J., Fança, B., Bluet, B., Jacqueroud, M. P., Seegers, J., Charroin, T. & Le Cozler, Y. (2023). Evaluating net energy and protein feed conversion efficiency for dairy ruminant systems in France. Livestock Science, 269, 105170. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2023.105170

- Rutherfurd, S. M., Fanning, A. C., Miller, B. J., & Moughan, P. J. (2015). Protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores and digestible indispensable amino acid scores differentially describe protein quality in growing male rats. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(2), 372-379. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.195438

- Shepon, A., Eshel, G., Noor, E., & Milo, R. (2016). Energy and protein feed-to-food conversion efficiencies in the US and potential food security gains from dietary changes. Environmental Research Letters, 11(10), 105002. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/10/105002

- SPGE. (2024). Bouclage biomasse : enjeux et orientations. https://www.info.gouv.fr/upload/media/content/0001/10/00d496ed6c39499c18e94e799f0803c87649b3f5.pdf

- Steinfeld, H., Haan, C. d., & Blackburn, H. (1997). Livestock - Environment Interactions: Issues and Options. European Commission Directorate-General for Development, Development Policy Sustainable Development and Natural Resources.

- van Zanten, H. H. E., Meerburg, B. G., Bikker, P., Herrero, M., & de Boer, I. J. M. (2016). Opinion paper: the role of livestock in a sustainable diet: a land-use perspective. Animal, 10(4), 547-549. doi:10.1017/S1751731115002694

- Wilkinson, J. M. (2011). Re-defining efficiency of feed use by livestock. Animal, 5(7), 1014-1022. doi:10.1017/S175173111100005X

- Wirsenius, S. (2003). The biomass metabolism of the food system: a model‐based survey of the global and regional turnover of food biomass. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 7(1), 47-80. https://doi.org/10.1162/108819803766729195

Résumé

Alors que les aliments d'origine animale représentent 25 % des protéines consommées par l'Homme dans le monde et sont reconnus pour leur qualité nutritionnelle, l'élevage est régulièrement critiqué pour son inefficience. En particulier, l’utilisation d’aliments comestibles par l’Homme et de terres cultivables pour produire de l’alimentation à destination de l’animal posent question. De nombreux indicateurs ont été développés afin d’objectiver l’apport des élevages à la fourniture d’alimentation humaine : l’efficience nette de conversion des protéines et de l’énergie, l’utilisation des terres arables, le land use ratio et la productivité nette. Ces indicateurs, qui existent avec plusieurs variantes, sont décrits, analysés et évalués sur base d’une compilation de différentes bases de données d’élevages bovins lait et viande. L’analyse démontre l'intérêt de nombreux systèmes ruminants et permet d’identifier des marges d’améliorations, notamment en basant les systèmes sur l’herbe et en réduisant l’utilisation des matières premières directement utilisables en alimentation humaine.

Pièces jointes

Pas de document complémentaire pour cet article##plugins.generic.statArticle.title##

Vues: 3588

Vues: 3588

Téléchargements

PDF: 132

PDF: 132

XML: 84

XML: 84

Articles les plus lus par le même auteur ou la même autrice

- Élisabeth BAÉZA-CAMPONE, Vincent CHATELLIER, Catherine HURTAUD, Anne FARRUGGIA, René BAUMONT, Avant-propos : Conséquences de la crise sanitaire de la Covid-19 sur les productions animales , INRAE Productions Animales: Vol. 34 No 4 (2021)

- René BAUMONT, Hommage à Daniel Sauvant, enseignant et chercheur en nutrition animale , INRAE Productions Animales: Vol. 35 No 3 (2022)

- Emmanuelle CARAMELLE-HOLTZ, Sylvie ANDRÉ, Anne-Charlotte DOCKES, René BAUMONT, Les rencontres autour des recherches sur les ruminants : 30 ans de partenariat entre INRAE et l’Institut de l’Élevage , INRAE Productions Animales: Vol. 38 No 2 (2025)

- René BAUMONT, Jean-Louis PEYRAUD, Avant-propos , INRAE Productions Animales: Vol. 28 No 1 (2015)

- René BAUMONT, Jean-Marc PEREZ, Editorial , INRAE Productions Animales: Vol. 25 No 1 (2012)