Immunophenotyping and possible applications for poultry breeding (Full text available in English)

Immunophenotyping is a technique that gathers immune parameters not only after a challenge but also in the basal state and is, therefore, a source of indicators of immunocompetence. This summary presents strategies for measuring immunocompetence, lists the available tools for immunophenotyping, and discusses the possible applications for the genetic improvement of poultry.

Introduction

Some domestic animals are more resistant to disease, respond better to vaccination, or, more generally, show greater robustness throughout their lives. Understanding what determines this variability and having measurable indicators of it would make it possible to consider new selection criteria.

The development of effective breeding programmes for production traits and the application of strict health rules under mostly well-controlled rearing conditions have led to highly significant improvements in zootechnical performance over the last 30 years (Siegel, 2014). However, new considerations linked to animal welfare, consumer safety and the introduction of new directives in Europe have led to the elimination of the use of antibiotics as growth promoters and the limitation of medicated prophylaxis, as well as changes in rearing conditions, with the elimination of cages and more access to open range. Demand is therefore moving towards more efficient, sustainable, and responsible production, while meeting society's new expectations in terms of animal health and welfare. In addition, chronic or emerging pathologies exist in livestock farming and represent major economic losses that the industry is keen to reduce.

It is sometimes difficult to reconcile these different expectations. For example, during outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza, exit restrictions are put in place to control the epidemic. Genetic selection of poultry for higher growth rates has resulted in lower disease resistance or reduced immune response (van der Most et al., 2011).

Veterinary vaccines are essential for protecting animals and public health (Jorge & Dellagostin, 2017). They help minimise animal suffering, promote efficient food production, and reduce the need for antibiotics to treat animals. They help prevent the transmission and spread of contagious animal diseases, including zoonoses that can be transmitted from animal to human or between animals.

Some domestic animals are more resistant to disease, respond better to vaccination, or, more generally, show greater robustness throughout their lives. It is important to understand why in order to define good predictors for introducing new health criteria into breeding objectives to produce domestic animals that are more resistant overall to various pathologies and stresses, and that develop an effective immune response after vaccination.

Immunophenotyping (or measurement of immune variables) makes it possible not only to monitor changes in the immune response following an immune challenge (vaccination, infection) but also to assess the potential effects on immunity of other types of disturbance that animals may encounter in rearing, such as stress, climatic variations, or rearing conditions. In addition, immunophenotyping animals during their lifetime in rearing conditions, without any major disturbance being identified a priori, can provide information on their immune status and potentially their immunocompetence, i.e., their ability to trigger an effective immune response in response to pathogens.

This article looks at the strategies for measuring immunocompetence. The tools available for immunophenotyping in genetic studies in poultry are reviewed, and the conditions for considering applications for the genetic improvement of poultry are discussed.

In functional terms, the immune system is composed of an early-reacting innate immune system and a slow-reacting adaptive immune system.

Innate immunity is the first line of defence against infection.

- It includes physical and chemical barriers in the epithelial layer of organs such as the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract, which prevent the penetration of microbes.

- Innate immunity also enables damaged cells to be eliminated and tissue repair to begin.

- The innate immune system fights microorganisms by using cells such as macrophages, granulocytes (polymorphonuclear cells such as heterophils), thrombocytes, basophils, eosinophils, and natural killer cells.

- Pathogens are identified by these cells by using receptors that recognise molecular patterns characteristic of microorganisms. PRR (Pattern Recognition Receptor) is the term to describe these cell receptors that are capable of recognising molecular patterns unique to pathogens, known as PAMPs (Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns).

- When they detect a danger, the cells of the innate immune system react by producing or releasing molecules such as defensins, cytokines, and chemokines, which coordinate the recruitment and action of a series of specialised cell populations with phagocytic and lytic functions. These innate immune responses are mainly nonspecific to pathogens.

Adaptive immunity is necessary to defend against specific pathogens and creates an immune memory that protects against future exposure.

Several mechanisms come into play:

- Humoral immunity: the antigen (infectious agent) directly activates B lymphocytes, which have specific receptors. The activated B lymphocytes then become plasma cells that secrete specific antibodies to destroy the antigen.

- Cellular immunity: the antigen is presented to T lymphocytes by antigen-presenting cells (e.g., dendritic cells). These cells activate T lymphocytes that differentiate into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+) to destroy infected cells.

- T lymphocytes can also differentiate into helper T lymphocytes (CD4+) that stimulate B lymphocytes to produce a greater quantity of antibodies and memory cells.

1. Strategies for assessing immunocompetence

1.1 Concept and definition of immunocompetence

Immunocompetence represents "the ability of the body to produce an appropriate and effective immune response when exposed to a variety of pathogens" (Hine et al., 2014). It is " a measure of the ability of an organism to minimise the fitness costs of an infection via any means" (Owens & Wilson, 1999). It is therefore the set of immune functions that promote resistance or tolerance to disease and control inflammation during infectious diseases or other inflammatory stresses. Immunocompetence thus contributes to resilience, considered as an animal's ability to maintain its productivity in the face of various environmental, biotic, or abiotic challenges (Bishop, 2012).

More recently, the concept of immune resilience has emerged. It is defined as the ability to preserve or rapidly restore immunocompetence following pathogenic or other stress (Ahuja et al., 2023). Immunocompetence is thus a concept to be considered throughout an animal's life.

Integrated health management strategies that include a genetic approach to improving immunocompetence and immune resilience thus have the potential to help reduce both the incidence and severity of disease. This would improve animal health and welfare and reduce the need for drugs to prevent and treat infectious diseases.

1.2 Strategies for measuring immunocompetence

a. Direct strategy: resistance/tolerance to a particular pathogen

To assess immunocompetence, direct strategies target the resistance or tolerance of animals to specific pathogens. The strategy assumes that if an immune response is highly specific to a given antigen, then the ability to produce a functionally effective immune response could be largely a generic trait. Measurement of the immune response to one pathogen would therefore be likely to be representative of responses to other pathogens. However, this is not always the case. An animal's response to a given pathogen is not necessarily linked to its response to other pathogens, as has been demonstrated in Drosophila and crickets (Fellowes et al., 1999; Letendre et al., 2022). The response mechanisms sometimes differ and are negatively correlated. This was demonstrated in mice (Biozzi et al., 1975) that were selected to produce high (H) or low (L) quantities of antibodies in response to an injection of sheep erythrocytes. While H mice were more resistant to infection by Trypanosoma cruzi (Kierszenbaum & Howard, 1976) and Nematospiroides dubius (Jenkins & Carrington, 1981), they were more susceptible to Salmonella typhimurium (Plant & Glynn, 1982), Brucella (Cannat et al, 1978), Leishmania tropica (Hale & Howard, 1981), and mycobacterial infection (Lagrange et al., 1979). In dairy cattle, Thompson-Crispi et al (2012) reported an unfavourable genetic correlation between the cellular immune response (delayed hypersensitivity to Candida albicans) and humoral responses (antibodies produced following immunisation with hen egg white lysozyme).

Genetic selection for resistance to a pathogen could have counterproductive effects in the long term by exerting selection pressure that could lead to escape strategies by pathogens and reduce the effect of selection for disease resistance (Hulst et al., 2022). This direct strategy seems risky, and further research is needed to assess the long-term effects of selection for resistance to a specific disease on the susceptibility to other diseases.

b. Indirect strategy: measurement of a panel of immune variables

An indirect and supposedly global approach focuses on analysing the individual variability of a panel of immune parameters that would make it possible to predict responses to pathogens in general. Blood is a valuable source of information about the body's overall metabolism and the immune status of animals (Chaussabel, 2015). It is also relatively easy to access, making it the compartment of choice for this search for parameters indicating immunocompetence.

The variables measured must reflect the different types of immunity (Box 1) developed during infections by pathogens or during vaccination, i.e, innate or adaptive immunity (passively transmitted maternal antibodies, humoral and cellular responses).

Various methods have been proposed to measure immunocompetence indexes in cattle (Wilkie & Mallard, 1999; Reverter et al., 2021) or broilers (Sivaraman & Kumar, 2013). These methods are based in particular on measurements of cellular and humoral responses following vaccination. However, the response to vaccination does not reflect the full immune potential of the animals. In particular, it is not clear that a response to vaccination fully reflects what happens during an infection. Furthermore, these measurements (particularly of the cellular response to vaccination) are fairly complex to implement routinely.

Other variables, such as those described below, which reflect other aspects of immunity, could be used, in a complementary manner, to determine whether there are correlations between immunocompetence parameters and responses to different pathogens and the significance of such correlations.

2. Immunophenotyping of poultry: what measurement options are suitable for genetic studies?

For measurements to be suitable for genetic studies, it is important to be able to collect them from a large number of individuals and, ideally, on the evolution of the animals throughout their lives. A large number of samples requires rigorous management and a great deal of expertise when it comes to taking samples (Samour, 2009) (blood tubes with suitable anticoagulants: usually heparin tubes for functional analyses and tubes with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for haematological measurements, animal identification, traceability of samples), preparing blood tubes in the laboratory (preparation of plasmas, aliquots, and storage), and carrying out the various measurements. Storage time and conditions must be appropriately adapted for all measured variables. Repeatable and standardised protocols are also essential to obtain robust data. The practical feasibility and cost of the measurements are also important criteria for these studies.

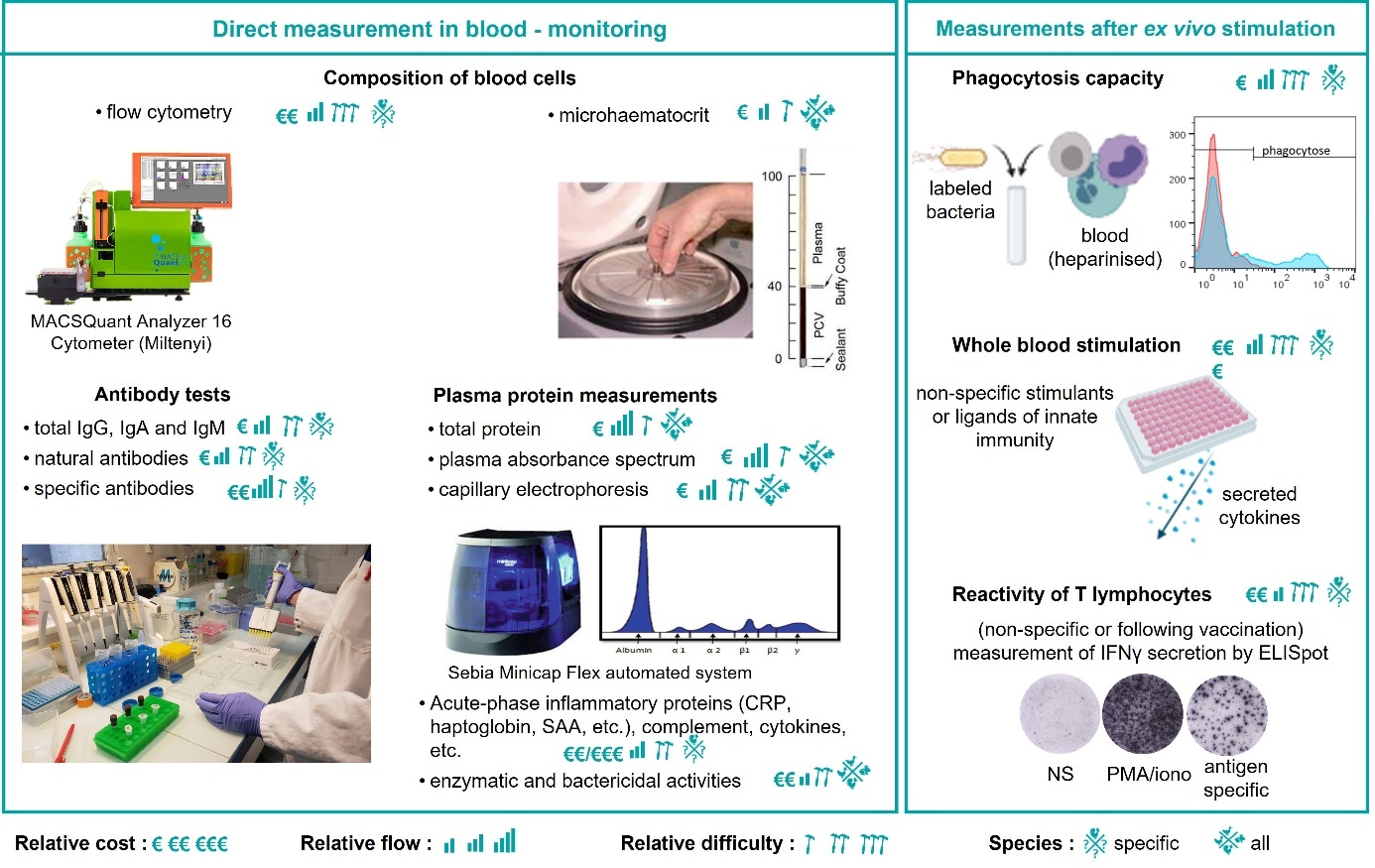

Depending on the species under consideration, there are more or fewer tools available to measure variables in the laboratory. For some species, this limits the possibilities of analysis or parameter precision. Proposed here is a list and descriptions of the immune variables that can be measured in chickens, mainly in the blood (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Immunophenotyping in chickens.

2.1. Direct measurement in blood - monitoring

a. Analysis of blood cell composition

Analysis of blood cell composition is used in human and veterinary medicine to assess an individual's immune and health status (Samour, 2009). Granulocytes, monocytes, and natural killer cells are involved in the detection and immediate elimination of pathogens, as well as in the transmission of signals to other cells. B and T lymphocytes develop a highly specific response to a particular antigen and create an immunological memory with the ability to respond very quickly and effectively to pathogens on a second encounter. Changes in the counts or proportions of an individual's leukocytes may be indicative of viral, bacterial or parasitic infections, toxin-induced immunosuppression, stress, or acute inflammation (Fairbrother & O'Loughlin, 1990; Maxwell & Robertson, 1998; Samour, 2009).

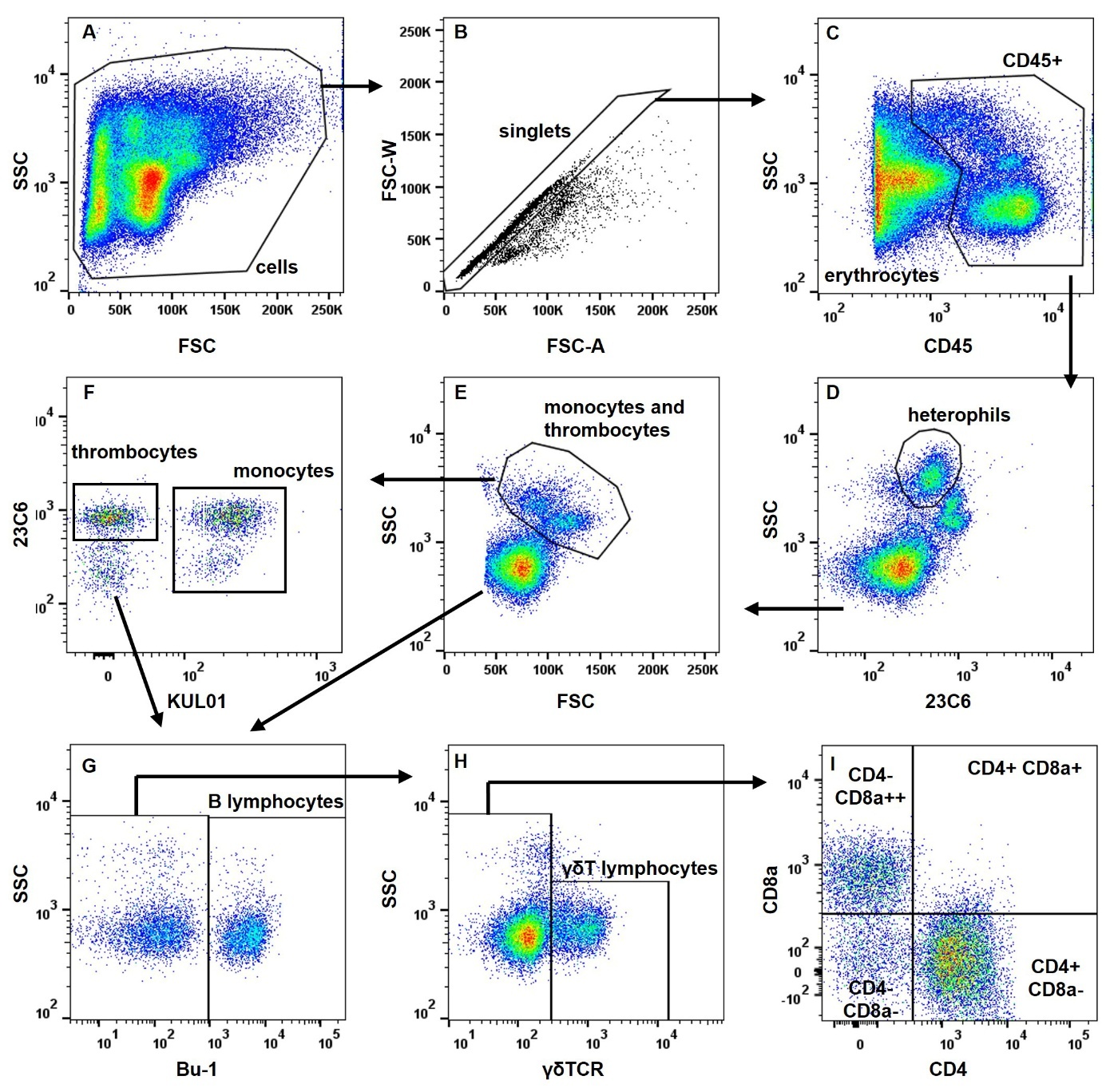

Automated blood counts using haemacytometers are a rapid and accurate technique used in mammals. However, these systems do not distinguish between erythrocytes, thrombocytes, and leukocytes in birds, as all these cells are nucleated. The use of antibodies specific to blood cell populations is therefore necessary for automated flow cytometry analysis in avian species. The availability of these antibodies varies greatly from species to species. In chickens, several strategies have been developed (Fair et al., 2008; Seliger et al., 2012; Bílková et al., 2017). Figure 2 illustrates the counting and identification of blood cells using relatively high-throughput flow cytometry. Depending on the age and lineage of the animals, differences may be observed in the expression of certain markers, and the blood cell identification strategy must be adapted.

Figure 2. Analysis of blood cell composition in chickens using flow cytometry.

Based on these analyses, certain calculated ratios can be used as markers of stress, such as the heterophil/lymphocyte ratio (Lentfer et al., 2015), or the balance between humoral and cellular immunity, such as the CD4/CD8 ratio. Indeed, a balance towards CD4+ T cells would represent an antibody-dominated response and a balance towards CD8+ T cells a cell-mediated response. In humans, a low CD4/CD8 ratio is associated with impaired immune function, immune senescence and chronic inflammation (McBride & Striker, 2017).

In addition to absolute count data and the percentage of each cell type, expression levels of certain markers may also be parameters to consider when assessing immunocompetence, as they are indicative of cell activation status, for example, CD8α expression by γδT lymphocytes (Pieper et al., 2011).

Cross-reactions between antibodies directed against different markers of chicken immune cells, such as CD4 or CD8, and cells of other avian species have been reported but need to be confirmed (Lu et al., 2023). In any case, these antibodies would not allow identifications as complete and precise as those possible in chickens. For ducks, an analysis of the various blood leukocytes was established by flow cytometry by using a combination of newly generated monoclonal antibodies and antibodies that cross-react with chicken (Jax et al., 2023). In turkeys, it is possible to use antibodies cross-reacting with chickens (Lindenwald et al., 2019).

For species for which there are no specific antibodies on the market or crossing with other species, certain flow cytometry analysis strategies based on cell size and structure (using a fluorescent dye to stain organelles) have been proposed (Uchiyama et al., 2005). Finally, the production of stained blood smears may be the only solution for identifying different cell types, but this is a more laborious and less accurate technique that requires specialist expertise. The emergence and availability of artificial intelligence algorithms for image analysis could considerably help the routine analysis of these slides (Sparavigna, 2017).

Other parameters are assessed when blood formulae are produced, in particular various characteristics of the red blood cells (e.g., volume, haemoglobin content). Some of these measurements are easy to perform, such as assessing haematocrit (the fraction of red cells in blood) after centrifuging microhaematocrit tubes.

b. Measurement of antibody levels

Three classes of immunoglobulins (Ig) (IgA, IgM and IgY) exist and can be measured in chickens. The presence of antibodies homologous to mammalian IgE and IgD has also been suspected (Carlander et al., 1999), but there are no antibodies specific to these classes of Ig for measuring them. IgM is the first antibody expressed during the immune response. It acts as a receptor on the surface of B lymphocytes and plays an important role in activating the complement system. IgA has an immune defence role in mucous membranes. Avian IgY is genetically and structurally different from its mammalian counterpart, IgG, but functionally plays similar biological roles. IgY and IgG are major immunoglobulins that provide defence against infectious agents and appear in the bloodstream in high concentrations following exposure to an antigen.

Different types of antibodies can be measured using ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) tests or according to their activity, for example, their ability to agglutinate antigen-coated particles (haemagglutination), to neutralise viruses or to promote phagocytosis (opsonisation).

Measurement of total antibody levels to the three different subtypes can reflect overall humoral immunity (Kramer et al., 2003). Natural antibodies are present in a healthy individual without the need for prior exposure to an exogenous antigen and considered a humoral part of innate immunity. They have a wide repertoire of specificity and act as a first line of defence against infections (Palma et al., 2018). In laying hens, high levels of natural antibodies have been associated with a higher probability of survival during the laying period (Star et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2011; Wondmeneh et al., 2015) and protection against infection by Escherichia coli (Berghof et al., 2019). Pathogen-specific antibodies are measured to monitor humoral responses following infections or vaccinations. Numerous ELISA kits are marketed by various suppliers, with varied possibilities depending on the poultry species.

c. Measurement of plasma proteins or enzymatic and bactericidal activities

Serum or total plasma protein levels can be measured using a variety of methods. As refractometry can be biased by lipemia, other methods such as the biuret method or the BiCinchoninic acid assay method are preferable. A decrease in total protein may indicate chronic haemorrhaging, poor intestinal absorption, liver or kidney failure, or immunosuppression. Conversely, dehydration or an inflammatory condition may result in an increase in total protein. The reproductive activity of females also leads to an increase in total protein (Harr, 2009).

Serum or plasma protein electrophoresis separates protein components into six main fractions based on their size and electrical charge (albumin, α1-, α2-, β1-, β2-, and γ-globulins). A capillary electrophoresis machine can be used to obtain a relatively high throughput with a small sample volume. The α-globulin fractions are comprised of acute-phase inflammatory proteins such as α-lipoprotein, α1-antitypsin, α2-macroglobulin, and haptoglobin. The β-globulin fractions include fibrinogen, β-lipoprotein, transferrin, and complement proteins. Increases in α- and β-globulin levels have been described during parasitic, bacterial, and fungal infections (Harr, 2009; Hamzic et al., 2015). The γ-globulin fraction mainly contains immunoglobulins. Plasma protein electrophoreses have the advantage of being used for all poultry species, as no specific reagents are required. However, the interpretation of the profiles may differ among species.

A more precise examination of specific molecules for the different functions they perform during the immune response (innate and acquired) can also be informative. These molecules circulate in the basal state and are over-expressed during chronic inflammation and infection or after vaccination (Janmohammadi et al., 2020). Measurements of acute-phase inflammatory proteins (C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A protein, haptoglobin; O'Reilly & Eckersall, 2014), certain complement components, and cytokines are therefore a potential source of immunocompetence parameters.

The activities of some of these molecules can also be measured as enzymatic activities: lysozyme, peroxidase, and reactive oxygen species (Oke et al., 2024). Measuring bactericidal activity could also reveal the activity of antimicrobial peptides (Cuperus et al., 2013).

d. Blood transcriptome or proteome

Unbiased approaches measuring the blood transcriptome or proteome can also be considered as a source of biomarkers of immunocompetence (Burgess, 2004; Désert et al., 2016). These analyses are very comprehensive but very costly to carry out on a very large scale.

2.2. Variables measured after ex vivo stimulation

One type of measurement of immune variables is based on the analysis of cell responses following ex vivo stimulation. These measurements generally require the use of fresh cells. Although this is sometimes technically possible, freezing cells is not indicated because the variability of the phenotype measured could be affected by the quality of the freezing and lead to a very strong experimental bias. Therefore, these measurements require intensive laboratory work within a limited timeframe.

a. Phagocytosis capacity

The immune system uses the process of phagocytosis to destroy cells infected by pathogens. Relatively rapid methods exist for assessing the overall phagocytosis capacity of blood cells by evaluating the internalisation of the dye neutral red (Song et al., 2022). Flow cytometry can also be used to measure the phagocytosis of particles or bacteria labelled with a fluorochrome. In avian species, this must be combined with labelling with an anti-CD45 antibody. The phagocytosis activities of different cell types identified by their size and structure can then be measured (Naghizadeh et al., 2019).

b. Whole blood stimulation

The reactivity of blood cells to different stimuli is considered a measure of immunocompetence. A wide range of stimuli can be used, such as whole bacteria and viruses or specific agonists of different innate immunity receptors (Duffy et al., 2014; Reid et al., 2021; Lesueur et al., 2022). In humans, many questions remain as to the nature of this interindividual variation in the immune response, but these tests could provide a better understanding of the differences in individual susceptibility to infectious diseases, the development of chronic inflammatory diseases, or autoimmunity (Müller et al., 2024). The same applies to farm animals. The adaptation of whole blood stimulation to poultry is based on the possibility of measuring the cytokine signature following stimulation. In chickens, there are ELISA tests that measure cytokines individually and even in multiplex assays. The Milliplex assay, for example, enables simultaneous quantification of all of the following analytes: alpha and gamma interferons (IFN), interleukins 2, 6, 10, 16, and 21, macrophage inflammatory proteins 1β and 3a, RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), CSF-1 (colony stimulating factor-1) and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor).

c. T cell activity

The activity of T cells in the circulation (non-destructive sampling) or in the spleen or lymph nodes (destructive sampling) can be determined by measuring their ability to proliferate or secrete cytokines produced in response to exposure to a mitogen or antigen. ELISpot assays for IFNγ are particularly sensitive and indicated for assessing cellular response to vaccination (Hao et al., 2021).

3. What applications can be envisaged for the genetic improvement of poultry?

3.1 Immunophenotyping: a source of immunocompetence indicators

Poultry immunophenotyping is used to measure the immune response induced by infection or vaccination. Of the many immune variables that can be measured, while some are described as being modulated during these immune challenges, none necessarily measures the effectiveness of the immune response. However, by comparing clinical and immunological parameters within a host population, it is possible to identify robust immunological protection criteria.

A 'good' response to vaccination is not necessarily determined by a large quantity of antibodies produced. If seropositivity thresholds are established, the correlation with vaccine efficacy is not so simple. For example, for intracellular pathogens such as parasites in the genus Eimeria, the antibody response is not a reliable indicator of protection against the pathogen. The reference test for assessing the protective efficacy of vaccines is still to look at their response following an infection (presence and transmission of the pathogen, clinical signs, and performance) (Soutter et al., 2020). The duration of onset and persistence of immunity are also important, although the relevance of these variables varies according to the target population (for example, while the duration of onset is more important in broilers, which are slaughtered very young, a persistent response is beneficial over a longer period in laying hens).

In the event of infection, immune responses should also be assessed in terms of how effectively they protect an individual. From an immunological point of view, more is not necessarily better. The maximum immune response is not necessary in all cases. Sometimes, the damage caused by a runaway immune system is significant. This is the case, for example, when hens are infected with the influenza virus, but not ducks (Burggraaf et al., 2014). The search for protection indicators (at the level of the individual and the flock or even the territory) remains a challenge to measuring effective responses to vaccinations and infections. In this context, immunophenotyping data are important sources of potential indicators (Hamzic et al., 2015).

Immunophenotyping of animals in their basal state could be used to assess their immunocompetence. It is no longer a question of determining indicators of responses but rather predictors of these responses. Acquiring knowledge of immunophenotyping data on animals before and after various disturbances is still crucial for determining parameters indicative of immunocompetence. Target and optimum values for these immune parameters still need to be defined before they can be used effectively in genetic selection.

3.2. Individual variability of immune parameters and genetic determinism

To determine whether immunocompetence parameters can be exploited in selection programmes, it is necessary to understand and determine what the characteristics of a healthy immune system are, what the factors of variation - genetic and environmental - are in the immune parameters measured, and what the significance of their variation is.

In different species, including poultry, there is considerable variability in responses to vaccination, infection, or other abiotic stresses. There is also considerable individual variability in basal state immune parameters. In hens, the effects of sex (Minozzi et al., 2007; Jax et al., 2023), age (Song et al., 2021; Jax et al., 2023), and rearing method are often reported (Hofmann et al., 2020; Song et al., 2022; Sarrigeorgiou et al., 2023). Although significant, these effects are generally moderate. For example, broilers reared on the ground showed 10–15% more IgG or lysozyme activity than those reared in cages (Song et al., 2022). The effects of the microbiota on immune variables are also being studied by using models of disruption by antibiotics (Schokker et al., 2017; Lecoeur et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022) or by association analyses (Aruwa et al., 2021; Borey et al., 2022).

The effects of genetics are assessed by comparing different breeds or by selecting divergent lines for immune traits, and they are assessed at the level of individual variability within populations (heritability measurements to assess the part attributed to genetics in the variability of immune parameters, searching for regions of the genome that influence a trait to identify the genes involved).

a. Breed comparison

By comparing breeds reared in the same environment, it is possible to highlight the effect of genetics on different variables. These comparisons reflect a combination of artificial and natural selection acting on traits linked to health and stress. This has been demonstrated in hens, for example, for blood cell composition (Bílková et al., 2017), natural antibodies (Sun et al., 2011), and other variables (Kramer et al., 2003). In a comparison of six breeds reared in the same environment and of the same age, the composition of blood cells proved to be highly variable, with lymphocytes representing 54–75% and heterophils 14–31% of leukocytes in the most extreme breeds. Differences in response to vaccination have also been demonstrated (Lecoeur et al., 2024). Comparing the immune parameters of breeds known to be more or less resistant to various infections would make it possible to identify general patterns of similarity that would explain these differences in immunocompetence. Furthermore, these differences among breeds or lines could be exploited in cross breeding to obtain more robust animals.

b. Selection of divergent lines

Several studies have reported divergent selection of poultry based on the quantification of immune variables, showing the existence of genetic control of variation in the immune parameters. For example, the role of host genetics in variation to vaccine response was demonstrated by genetic selection of White Leghorn laying hens for a high humoral response to vaccination against Newcastle disease virus (NDV), a high cell-mediated immune response, and a high phagocytic activity (Pinard-van der Laan, 2002). Other selection experiments have been carried out on antibody response (Dan Heller et al., 1992; Parmentier et al., 2004), the presence of natural antibodies (Berghof et al., 2019), and the ratio of the number of heterophils to the number of lymphocytes (H/L ratio) (Wang et al., 2023). Selections based on immunocompetence indexes defined by several parameters have also been successfully carried out (Kean et al., 1994; Sivaraman & Kumar, 2013).

With these divergent selection experiments, it is possible to study the impact of selection on the health and welfare of the animals. For example, a line selected for humoral response to NDV vaccination also had increased humoral responses to other commercial vaccines, and fewer blood leukocytes than the unselected control line (Zerjal et al., 2021). In this study, it was also reported that the selected animals had reduced body weight. Another selection experiment on antibody response following immunisation with inactivated E. coli showed that the response was associated with a high antibody response against other antigens, as well as increased phagocytic activity and cellular response (Dan Heller et al., 1992). Selection for high levels of natural antibodies resulted in increased resistance to E. coli infection (Berghof et al., 2019) and humoral response to certain antigens (Berghof et al., 2018a). Selection based on the H/L ratio showed that selection for a low H/L ratio improved resistance to Salmonella (Al-Murrani et al., 2002).

It should be noted that these impacts may be linked to linkage disequilibrium and because the regions in the genome are close to each other, they may also be correlated since they share biological pathways. Thus, by studying the genes present in the divergent regions, the causes of the observed phenotypic differences can be sought. For example, resistance to Salmonella can be explained by an increase in the function of heterophils in the breeding line with a low H/L ratio (Wang et al., 2023).

c. Heritability estimates

Heritability estimates have been calculated for some immune variables. Heritabilities of antibody response, T cell-mediated response, or phagocytosis in laying hens following in vivo challenges have been estimated at 0–0.22 (Cheng et al., 1991). Estimates of the heritability of the antibody response against different pathogens in a field study, under conditions of natural infection, showed that they were very different between the two populations studied and varied between 0.11 and 0.79 (Psifidi et al., 2016). Heritabilities between 0.07 and 0.14 were estimated for natural antibodies, varying according to the isotype considered (van der Klein et al., 2015), and for total antibodies at 0.06 for IgG, 0.22 for IgA, and 0.23 for IgM (Berghof et al., 2018b).

These heritabilities vary, therefore, according to the traits and populations studied. Heritability studies have not been conducted for all immune variables that can be immunophenotyped in poultry. However, for the studies that have been carried out, genetic determination of immune parameters has generally been confirmed, indicating that genetic selection for these traits is theoretically possible. Such traits that are targeted for selection tend to be subject to complex determinism. They are subject to the expression of many genes, generally unknown, and to environmental effects. The genetic value of an individual for a given trait reflects the effect of all the genes involved in the expression of that trait. It would therefore be possible to measure these traits in a phenotyped and genotyped reference population, making it possible to establish the statistical relationships between genotype and phenotype and, through genomic selection, to predict their genetic value in genotyped candidates.

d. Genetic association studies

Some genetic association studies have been performed on species of Gallus and have identified potential genome regions called quantitative trait loci (QTL) for quantitative immunity traits. For example, for natural antibodies and total antibodies, a region on chromosome 4 was found to be significantly associated with a likely causative variant in the TLR1A gene (Berghof et al., 2018b). Other potential QTL for immunity have been associated with natural and acquired antibody titres and complement reactivity, highlighting the roles of the IL17A, IL12B, and MHC genes in immune function (Biscarini et al., 2010). Zhang et al. (2015) revealed genetic associations between regions of the genome and IgY levels, quantities of heterophils and lymphocytes in the blood, and antibody responses to an influenza virus vaccine or sheep erythrocyte injection.

e. Towards the study of the hologenetic determination of immunocompetence parameters

An animal’s microbiota can also affect the immune variables and the animal's response to infection. For example, the administration of antibiotics or probiotics exerts immunomodulatory effects on the immune variables, particularly in the blood (Jankowski et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022). Taking into account the microbiota in addition to genetics has made it possible to improve the prediction of immune traits in pigs (Calle-García et al., 2023). Integrating the information on microbiota and host-microbiota interactions will require changes in genetic evaluation models to take into account this hologenetic determinism (Estellé, 2019).

3.3 Phenotypic and genetic correlations between immunocompetence and other important functions

Phenotypic and genetic relationships between immunocompetence and production traits need to be assessed in the context of resource allocation theory, as investing resources in one functional area may be detrimental to others (Friggens et al., 2017). For example, the genetic selection of poultry for a higher growth rate or better performance has resulted in a reduction in disease resistance or a reduction in the immune response (Bayyari et al., 1997; van der Most et al., 2011; Zerjal et al., 2021). Cheema et al. (2003) compared the immunocompetence parameters of the 2001 Ross 308 broiler strain with those of a 1957 control strain. Genetic selection to improve broiler performance has resulted in a reduction in the adaptive component of the immune response, but an increase in cell-mediated and inflammatory responses.

However, other studies have reached different conclusions based on other parameters. Kean et al. (1994) showed that divergent selection for immune parameters had no impact on egg-laying production parameters. Psifidi et al. (2016) found no significant genetic correlations between immunity traits, clinical signs of disease, and production performance. Finally, comparing historical and modern lines, O'Reilly et al. (2018) showed that acute-phase inflammatory protein concentrations were not affected by selection.

It is therefore necessary to explore the trade-offs between immune functions and performance in the various studies carried out. It is essential to know the genetic correlations between the new immunocompetence traits identified and the other selection criteria in the synthetic index to optimise the economic weight given to each trait. Study of the relationship between immunity and animal welfare in the context of sustainable breeding is also needed.

Conclusion

Exploiting spontaneous variability in immune characteristics to genetically improve the immunocompetence of domestic animals is a promising approach, integrating it in a complementary way with current strategies such as vaccination to promote sustainable breeding. However, it would be necessary to target more pertinently the immune parameters that define an animal's immunocompetence and immune resilience and to integrate all the knowledge acquired about the parameters that control them and the trade-offs that may exist with other important traits such as performance, stress, and animal welfare, so that they can be exploited for the genetic improvement of poultry. Immunophenotyping of poultry has the potential to provide a better understanding and characterisation of the good health of animals and optimisation of their immunocompetence. Questions are being asked about the selection strategies that should be applied for these immunocompetence traits. What weight should be given to these new traits? The use of epidemiogenetic modelling appears to be an interesting approach here. Generally, the economic impact of the costs of the new measures to phenotypically identify immunocompetence and the potential impact on performance, as well as the management of health risks, need to be considered.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Marie-Hélène Pinard-van der Laan for her proofreading and advice, the staff of the experimental units who daily looked after the animals, and the researchers and technicians of the Genetics, Microbiota and Health team at the INRAE GABI unit who are involved in these research questions.

This article was first translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and the author thanks Proof-Reading-Service.com Ltd for English language editing.

Notes

- 1. This article is based on an invited paper presented at the 15th Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie Gras, held on 20–21 March 2024 in Tours (Blanc, 2024).

References

- Ahuja, S. K., Manoharan, M. S., Lee, G. C., McKinnon, L. R., Meunier, J. A., Steri, M., Harper, N., Fiorillo, E., Smith, A. M., Restrepo, M. I., Branum, A. P., Bottomley, M. J., Orrù, V., Jimenez, F., Carrillo, A., Pandranki, L., Winter, C. A., Winter, L. A., Gaitan, A. A., … He, W. (2023). Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Nature Communications, 14(1), 3286. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6

- Al-Murrani, W. K., Al-Rawi, I. K., & Raof, N. M. (2002). Genetic resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in two lines of chickens selected as resistant and sensitive on the basis of heterophil/lymphocyte ratio. British Poultry Science, 43(4), 501-507. doi:10.1080/0007166022000004408

- Aruwa, C. E., Pillay, C., Nyaga, M. M., & Sabiu, S. (2021). Poultry gut health – microbiome functions, environmental impacts, microbiome engineering and advancements in characterization technologies. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 12(1), 1-15. doi:10.1186/s40104-021-00640-9

- Bayyari, G., Huff, W., Rath, N., Balog, J., Newberry, L., Villines, J., Skeeles, J., Anthony, N., & Nestor, K. (1997). Effect of the genetic selection of turkeys for increased body weight and egg production on immune and physiological responses. Poultry Science, 76(2), 289-296. doi:10.1093/ps/76.2.289

- Berghof, T. V. L., Arts, J. A. J., Bovenhuis, H., Lammers, A., van der Poel, J. J., & Parmentier, H. K. (2018a). Antigen-dependent effects of divergent selective breeding based on natural antibodies on specific humoral immune responses in chickens. Vaccine, 36(11), 1444-1452. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.063

- Berghof, T. V. L., Visker, M. H. P. W., Arts, J. A. J., Parmentier, H. K., van der Poel, J. J., Vereijken, A. L. J., & Bovenhuis, H. (2018b). Genomic region containing Toll-like receptor genes has a major impact on total IgM antibodies including KLH-binding IgM natural antibodies in chickens. Frontiers in Immunology, 8. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01879

- Berghof, T. V. L., Matthijs, M. G. R., Arts, J. A. J., Bovenhuis, H., Dwars, R. M., van der Poel, J. J., Visker, M. H. P. W., & Parmentier, H. K. (2019). Selective breeding for high natural antibody level increases resistance to avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) in chickens. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 93, 45-57. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2018.12.007

- Bílková, B., Bainová, Z., Janda, J., Zita, L., & Vinkler, M. (2017). Different breeds, different blood: Cytometric analysis of whole blood cellular composition in chicken breeds. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 188, 71-77. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2017.05.001

- Biozzi, G., Stiffel, C., Mouton, D., & Bouthillier, Y. (1975). Selection of lines of mice with high and low antibody responses to complex immunogens. In B. Benacerraf (Ed.), Immunogenetics and Immunodeficiency (p. 179-227). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-6135-0_5

- Biscarini, F., Bovenhuis, H., Van Arendonk, J. A. M., Parmentier, H. K., Jungerius, A. P., & Van Der Poel, J. J. (2010). Across‐line SNP association study of innate and adaptive immune response in laying hens. Animal Genetics, 41(1), 26-38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01960.x

- Bishop, S. C. (2012). A consideration of resistance and tolerance for ruminant nematode infections. Frontiers in Genetics, 3, 168. doi:10.3389/fgene.2012.00168

- Blanc, F. (2024). Immunophénotypage et applications envisageables pour l’amélioration génétique des volailles [Communication]. 15e Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie Gras, Tours. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-04515238v1

- Borey, M., Bed’Hom, B., Bruneau, N., Estellé, J., Larsen, F., Blanc, F., Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H., Dalgaard, T., & Calenge, F. (2022). Caecal microbiota composition of experimental inbred MHC-B lines infected with IBV differs according to genetics and vaccination. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 9995. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13512-7

- Burgess, S. C. (2004). Proteomics in the chicken: tools for understanding immune responses to avian diseases. Poultry Science, 83(4), 552-573. doi:10.1093/ps/83.4.552

- Burggraaf, S., Karpala, A. J., Bingham, J., Lowther, S., Selleck, P., Kimpton, W., & Bean, A. G. D. (2014). H5N1 infection causes rapid mortality and high cytokine levels in chickens compared to ducks. Virus Research, 185, 23-31. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.012

- Calle-García, J., Ramayo-Caldas, Y., Zingaretti, L. M., Quintanilla, R., Ballester, M., & Pérez-Enciso, M. (2023). On the holobiont ‘predictome’ of immunocompetence in pigs. Genetics Selection Evolution, 55(1), 29. doi:10.1186/s12711-023-00803-4

- Cannat, A., Bousquet, C., & Serre, A. (1978). Response of high and low antibody producer to Brucella. Annales d’immunologie, 129 C(5), 669-683. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/104653

- Carlander, D., Stålberg, J., & Larsson, A. (1999). Chicken Antibodies. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 104(3), 179-189. doi:10.3109/03009739909178961

- Chaussabel, D. (2015). Assessment of immune status using blood transcriptomics and potential implications for global health. Seminars in Immunology, 27(1), 58-66. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.002

- Cheema, M., Qureshi, M., & Havenstein, G. (2003). A comparison of the immune response of a 2001 commercial broiler with a 1957 randombred broiler strain when fed representative 1957 and 2001 broiler diets. Poultry Science, 82(10), 1519-1529. doi:10.1093/ps/82.10.1519

- Cheng, S., Rothschild, M. F., & Lamont, S. J. (1991). Estimates of Quantitative Genetic Parameters of Immunological Traits in the Chicken. Poultry Science, 70(10), 2023-2027. doi:10.3382/ps.0702023

- Cuperus, T., Coorens, M., van Dijk, A., & Haagsman, H. P. (2013). Avian host defense peptides. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 41(3), 352-369. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2013.04.019

- Dan Heller, E., Leitner, G., Friedman, A., Uni, Z., Gutman, M., & Cahaner, A. (1992). Immunological parameters in meat-type chicken lines divergently selected by antibody response to Escherichia coli vaccination. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 34(1-2), 159-172. doi:10.1016/0165-2427(92)90159-N

- Désert, C., Merlot, E., Zerjal, T., Bed’hom, B., Härtle, S., Le Cam, A., Roux, P.-F., Baéza, E., Gondret, F., Duclos, M. J., & Lagarrigue, S. (2016). Transcriptomes of whole blood and PBMC in chickens. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics, 20, 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.cbd.2016.06.008

- Duffy, D., Rouilly, V., Libri, V., Hasan, M., Beitz, B., David, M., Urrutia, A., Bisiaux, A., LaBrie, S. T., Dubois, A., Boneca, I. G., Delval, C., Thomas, S., Rogge, L., Schmolz, M., Quintana-Murci, L., & Albert, M. L. (2014). Functional analysis via standardized whole-blood stimulation systems defines the boundaries of a healthy immune response to complex stimuli. Immunity, 40(3), 436-450. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.002

- Estellé, J. (2019). Benefits from the joint analysis of host genomes and metagenomes: Select the holobiont. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 136(2), 75-76. doi:10.1111/jbg.12383

- Fairbrother, A., & O’Loughlin, D. (1990). Differential white blood cell values of the Mallard (Anas Platyrhynchos) across different ages and reproductive states. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 26(1), 78-82. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-26.1.78

- Fair, J. M., Taylor-McCabe, K. J., Shou, Y., & Marrone, B. L. (2008). Immunophenotyping of chicken peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations: Individual variability and repeatability. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 125(3-4), 268-273. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.05.012

- Fellowes, M. D. E., Kraaijeveld, A. R., & Godfray, H. C. J. (1999). Cross-resistance following artificial selection for increased defense against parasitoids in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution, 53(3), 966-972. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb05391.x

- Friggens, N. C., Blanc, F., Berry, D. P., & Puillet, L. (2017). Review: Deciphering animal robustness. A synthesis to facilitate its use in livestock breeding and management. Animal, 11(12), 2237-2251. doi:10.1017/S175173111700088X

- Hale, C., & Howard, J. G. (1981). Immunological regulation of experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. 2. Studies with Biozzi high and low responder lines of mice. Parasite Immunology, 3(1), 45-55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3024.1981.tb00384.x

- Hamzic, E., Bed’Hom, B., Juin, H., Hawken, R., Abrahamsen, M. S., Elsen, J. M., Servin, B., Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H., & Demeure, O. (2015). Large-scale investigation of the parameters in response to Eimeria maxima challenge in broilers. Journal of Animal Science, 93(4), 1830-1840. doi:10.2527/jas2014-8592

- Hao, X., Zhang, F., Yang, Y., & Shang, S. (2021). The Evaluation of Cellular Immunity to Avian Viral Diseases: Methods, Applications, and Challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.794514

- Harr, K. E. (2009). Diagnostic Value of Biochemistry. In G. J. Harrison & T. L. Lightfoot (Eds.), Clinical Avian Medicine (Vol. II, p. 611-630). Spix Publishing, Inc.

- Hine, B. C., Mallard, B. A., Ingham, A. B., & Colditz, I. G. (2014). Immune competence in livestock. In S. Hermesch & S. Dominik (Eds.), Breeding Focus 2014 – Improving Resilience. Animal Genetics and Breeding Unit, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia.

- Hofmann, T., Schmucker, S. S., Bessei, W., Grashorn, M., & Stefanski, V. (2020). Impact of housing environment on the immune system in chickens: A review. Animals, 10(7), 1138. doi:10.3390/ani10071138

- Hulst, A. D., Bijma, P., & De Jong, M. C. M. (2022). Can breeders prevent pathogen adaptation when selecting for increased resistance to infectious diseases? Genetics Selection Evolution, 54(1), 73. doi:10.1186/s12711-022-00764-0

- Jankowski, J., Tykałowski, B., Stępniowska, A., Konieczka, P., Koncicki, A., Matusevičius, P., & Ognik, K. (2022). Immune Parameters in Chickens Treated with Antibiotics and Probiotics during Early Life. Animals, 12(9), 1133. doi:10.3390/ani12091133

- Janmohammadi, A., Sheikhi, N., Nazarpak, H. H., & Nikbakht Brujeni, G. (2020). Effects of vaccination on acute-phase protein response in broiler chicken. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0229009. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229009

- Jax, E., Werner, E., Müller, I., Schaerer, B., Kohn, M., Olofsson, J., Waldenström, J., Kraus, R. H. S., & Härtle, S. (2023). Evaluating Effects of AIV Infection Status on Ducks Using a Flow Cytometry-Based Differential Blood Count. Microbiology Spectrum, 11(4), 1-15. doi:10.1128/spectrum.04351-22

- Jenkins, D. C., & Carrington, T. S. (1981). Nematospiroides dubius: the course of primary, secondary and tertiary infections in high and low responder Biozzi mice. Parasitology, 82(2), 311-318. doi:10.1017/S003118200005705X

- Jorge, S., & Dellagostin, O. A. (2017). The development of veterinary vaccines: a review of traditional methods and modern biotechnology approaches. Biotechnology Research and Innovation, 1(1), 6-13. doi:10.1016/j.biori.2017.10.001

- Kean, R. P., Cahaner, A., Freeman, A. E., & Lamont, S. J. (1994). Direct and Correlated Responses to Multitrait, Divergent Selection for Immunocompetence. Poultry Science, 73(1), 18-32. doi:10.3382/ps.0730018

- Kierszenbaum, P., & Howard, J. G. (1976). Mechanisms of resistance against experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection: the importance of antibodies and antibody-forming capacity in the Biozzi high and low responder mice. The Journal of Immunology, 116(5), 1208-1211. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.116.5.1208

- Kramer, J., Visscher, A. H., Wagenaar, J. A., Cornelissen, J. B. J. W., & Jeurissen, S. H. M. (2003). Comparison of natural resistance in seven genetic groups of meat-type chicken. British Poultry Science, 44(4), 577-585. doi:10.1080/00071660310001616174

- Lagrange, P. H., Hurtrel, B., & Thickstun, P. M. (1979). Immunological behavior after mycobacterial infection in selected lines of mice with high or low antibody responses. Infection and Immunity, 25(1), 39-47. doi:10.1128/iai.25.1.39-47.1979

- Lecoeur, A., Blanc, F., Gourichon, D., Bruneau, N., Burlot, T., Calenge, F., & Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H. (2022). Combined effect of genetics and gut microbiota on variations in vaccine response in hens. 12th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production (WCGALP), Rotterdam. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03798383v1

- Lecoeur, A., Blanc, F., Gourichon, D., Bruneau, N., Burlot, T., Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H., & Calenge, F. (2024). Host genetics drives differences in cecal microbiota composition and immune traits of laying hens raised in the same environment. Poultry Science, 103(5), 103609. doi:10.1016/j.psj.2024.103609

- Lentfer, T. L., Pendl, H., Gebhardt-Henrich, S. G., Fröhlich, E. K. F., & Von Borell, E. (2015). H/L ratio as a measurement of stress in laying hens - methodology and reliability. British Poultry Science, 56(2), 157-163. doi:10.1080/00071668.2015.1008993

- Lesueur, J., Walachowski, S., Barbey, S., Cebron, N., Lefebvre, R., Launay, F., Boichard, D., Germon, P., Corbiere, F., & Foucras, G. (2022). Standardized whole blood assay and bead-based cytokine profiling reveal commonalities and diversity of the response to bacteria and TLR ligands in cattle. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.871780

- Letendre, C., Duffield, K. R., Sadd, B. M., Sakaluk, S. K., House, C. M., & Hunt, J. (2022). Genetic covariance in immune measures and pathogen resistance in decorated crickets is sex and pathogen specific. Journal of Animal Ecology, 91(7), 1471-1488. doi:10.1111/1365-2656.13709

- Lindenwald, R., Pendl, H., Scholtes, H., Schuberth, H. J., & Rautenschlein, S. (2019). Flow-cytometric analysis of circulating leukocyte populations in turkeys: Establishment of a whole blood analysis approach and investigations on possible influencing factors. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 210, 46-54. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2019.03.006

- Lu, M., Lee, Y., & Lillehoj, H. S. (2023). Evolution of developmental and comparative immunology in poultry: The regulators and the regulated. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 138, 104525. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2022.104525

- Maxwell, M. H., & Robertson, G. W. (1998). The avian heterophil leucocyte: a review. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 54(2), 155-178. doi:10.1079/WPS19980012

- McBride, J. A., & Striker, R. (2017). Imbalance in the game of T cells: What can the CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio tell us about HIV and health? PLoS Pathogens, 13(11), e1006624. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006624

- Minozzi, G., Parmentier, H. K., Nieuwland, M. G. B., Bed’Hom, B., Minvielle, F., Gourichon, D., & Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H. (2007). Antibody responses to keyhole limpet hemocyanin, lipopolysaccharide, and newcastle disease virus vaccine in F2 and backcrosses of white leghorn lines selected for two different immune response traits. Poultry Science, 86(7), 1316-1322. doi:10.1093/ps/86.7.1316

- Müller, S., Kröger, C., Schultze, J. L., & Aschenbrenner, A. C. (2024). Whole blood stimulation as a tool for studying the human immune system. European Journal of Immunology, 54(2). doi:10.1002/eji.202350519

- Naghizadeh, M., Larsen, F. T., Wattrang, E., Norup, L. R., & Dalgaard, T. S. (2019). Rapid whole blood assay using flow cytometry for measuring phagocytic activity of chicken leukocytes. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 207, 53-61. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2018.11.014

- O’Reilly, E. L., & Eckersall, P. D. (2014). Acute phase proteins: A review of their function, behaviour and measurement in chickens. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 70(1), 27-44. doi:10.1017/S0043933914000038

- O’Reilly, E. L., Bailey, R. A., & Eckersall, P. D. (2018). A comparative study of acute-phase protein concentrations in historical and modern broiler breeding lines. Poultry Science, 97(11), 3847-3853. doi:10.3382/ps/pey272

- Oke, O. E., Akosile, O. A., Oni, A. I., Opowoye, I. O., Ishola, C. A., Adebiyi, J. O., Odeyemi, A. J., Adjei-Mensah, B., Uyanga, V. A., & Abioja, M. O. (2024). Oxidative stress in poultry production. Poultry Science, 103(9), 104003. doi:10.1016/j.psj.2024.104003

- Owens, I. P. F., & Wilson, K. (1999). Immunocompetence: a neglected life history trait or conspicuous red herring? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 14(5), 170-172. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01580-8

- Palma, J., Tokarz-Deptuła, B., Deptuła, J., & Deptuła, W. (2018). Natural antibodies – Facts known and unknown. Central European Journal of Immunology, 43(4), 466-475. doi:10.5114/ceji.2018.81354

- Parmentier, H. K., Lammers, A., Hoekman, J. J., de Vries Reilingh, G., Zaanen, I. T. A., & Savelkoul, H. F. J. (2004). Different levels of natural antibodies in chickens divergently selected for specific antibody responses. Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 28(1), 39-49. doi:10.1016/S0145-305X(03)00087-9

- Pieper, J., Methner, U., & Berndt, A. (2011). Characterization of avian γδ T-cell subsets after Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium infection of chicks. Infection and Immunity, 79(2), 822-829. doi:10.1128/IAI.00788-10

- Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H. (2002). Immune modulation: The genetic approach. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 87(3-4), 199-205. doi:10.1016/S0165-2427(02)00075-2

- Plant, J. E., & Glynn, A. A. (1982). Genetic control of resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection in high and low antibody responder mice. Clinical and Experimental Immunology, 50(2), 283-290. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6817955

- Psifidi, A., Banos, G., Matika, O., Desta, T. T., Bettridge, J., Hume, D. A., Dessie, T., Christley, R., Wigley, P., Hanotte, O., & Kaiser, P. (2016). Genome-wide association studies of immune, disease and production traits in indigenous chicken ecotypes. Genetics Selection Evolution, 48(1), 74. doi:10.1186/s12711-016-0252-7

- Reid, C., Beynon, C., Kennedy, E., O’Farrelly, C., & Meade, K. G. (2021). Bovine innate immune phenotyping via a standardized whole blood stimulation assay. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 17227. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-96493-3

- Reverter, A., Hine, B. C., Porto-Neto, L., Li, Y., Duff, C. J., Dominik, S., & Ingham, A. B. (2021). ImmuneDEX: a strategy for the genetic improvement of immune competence in Australian Angus cattle. Journal of Animal Science, 99(3), skaa384. doi:10.1093/jas/skaa384

- Samour, J. (2009). Diagnostic value of hematology. In G. J. Harrison & T. Lightfoot (Eds.), Clinical Avian Medicine (Vol. II, p. 587-610). Spix Publishing, Inc.

- Sarrigeorgiou, I., Stivarou, T., Tsinti, G., Patsias, A., Fotou, E., Moulasioti, V., Kyriakou, D., Tellis, C., Papadami, M., Moussis, V., Tsiouris, V., Tsikaris, V., Tsoukatos, D., & Lymberi, P. (2023). Levels of circulating IgM and IgY natural antibodies in broiler chicks: Association with genotype and farming systems. Biology, 12(2), 304. doi:10.3390/biology12020304

- Schokker, D., Jansman, A. J. M., Veninga, G., de Bruin, N., Vastenhouw, S. A., de Bree, F. M., Bossers, A., Rebel, J. M. J., & Smits, M. A. (2017). Perturbation of microbiota in one-day old broiler chickens with antibiotic for 24 hours negatively affects intestinal immune development. BMC Genomics, 18(1), 241. doi:10.1186/s12864-017-3625-6

- Seliger, C., Schaerer, B., Kohn, M., Pendl, H., Weigend, S., Kaspers, B., & Härtle, S. (2012). A rapid high-precision flow cytometry based technique for total white blood cell counting in chickens. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 145(1-2), 86-99. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.10.010

- Siegel, P. B. (2014). Evolution of the Modern Broiler and Feed Efficiency. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 2(1), 375-385. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022513-114132

- Sivaraman, G. K., & Kumar, S. (2013). Immunocompetence index selection of broiler chicken lines for disease resistance and their impact on survival rate. Veterinary World, 6(9), 628-631. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2013.628-631

- Song, B., Tang, D., Yan, S., Fan, H., Li, G., Shahid, M. S., Mahmood, T., & Guo, Y. (2021). Effects of age on immune function in broiler chickens. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 12(1), 42. doi:10.1186/s40104-021-00559-1

- Song, B., Li, P., Xu, H., Wang, Z., Yuan, J., Zhang, B., Lv, Z., Song, Z., & Guo, Y. (2022). Effects of rearing system and antibiotic treatment on immune function, gut microbiota and metabolites of broiler chickens. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 13(1), 144. doi:10.1186/s40104-022-00788-y

- Soutter, F., Werling, D., Tomley, F. M., & Blake, D. P. (2020). Poultry coccidiosis: Design and interpretation of vaccine studies. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7. doi:10.3389/fvets.2020.00101

- Sparavigna, A. C. (2017). Measuring the blood cells by means of an image segmentation. Philica. https://hal.science/hal-01654006

- Star, L., Frankena, K., Kemp, B., Nieuwland, M. G. B., & Parmentier, H. K. (2007). Natural humoral immune competence and survival in layers. Poultry Science, 86(6), 1090-1099. doi:10.1093/ps/86.6.1090

- Sun, Y., Parmentier, H. K., Frankena, K., & van der Poel, J. J. (2011). Natural antibody isotypes as predictors of survival in laying hens. Poultry Science, 90(10), 2263-2274. doi:10.3382/ps.2011-01613

- Thompson-Crispi, K. A., Sewalem, A., Miglior, F., & Mallard, B. A. (2012). Genetic parameters of adaptive immune response traits in Canadian Holsteins. Journal of Dairy Science, 95(1), 401-409. doi:10.3168/jds.2011-4452

- Uchiyama, R., Moritomo, T., Kai, O., Uwatoko, K., Inoue, Y., & Nakanishi, T. (2005). Counting absolute number of lymphocytes in quail whole blood by flow cytometry. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science, 67(4), 441-444. doi:10.1292/jvms.67.441

- van der Klein, S. A. S., Berghof, T. V. L., Arts, J. A. J., Parmentier, H. K., van der Poel, J. J., & Bovenhuis, H. (2015). Genetic relations between natural antibodies binding keyhole limpet hemocyanin and production traits in a purebred layer chicken line. Poultry Science, 94(5), 875-882. doi:10.3382/ps/pev052

- van der Most, P. J., de Jong, B., Parmentier, H. K., & Verhulst, S. (2011). Trade‐off between growth and immune function: a meta‐analysis of selection experiments. Functional Ecology, 25(1), 74-80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01800.x

- Wang, J., Zhang, J., Wang, Q., Zhang, Q., Thiam, M., Zhu, B., Ying, F., Elsharkawy, M. S., Zheng, M., Wen, J., Li, Q., & Zhao, G. (2023). A heterophil/lymphocyte-selected population reveals the phosphatase PTPRJ is associated with immune defense in chickens. Communications Biology, 6(1), 196. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-04559-x

- Wilkie, B., & Mallard, B. (1999). Selection for high immune response: an alternative approach to animal health maintenance? Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 72(1-2), 231-235. doi:10.1016/S0165-2427(99)00136-1

- Wondmeneh, E., Van Arendonk, J. A. M., Van der Waaij, E. H., Ducro, B. J., & Parmentier, H. K. (2015). High natural antibody titers of indigenous chickens are related with increased hazard in confinement. Poultry Science, 94(7), 1493-1498. doi:10.3382/ps/pev107

- Zerjal, T., Härtle, S., Gourichon, D., Guillory, V., Bruneau, N., Laloë, D., Pinard-van der Laan, M.-H., Trapp, S., Bed’hom, B., & Quéré, P. (2021). Assessment of trade-offs between feed efficiency, growth-related traits, and immune activity in experimental lines of layer chickens. Genetics Selection Evolution, 53(1), 44. doi:10.1186/s12711-021-00636-z

- Zhang, L., Li, P., Liu, R., Zheng, M., Sun, Y., Wu, D., Hu, Y., Wen, J., & Zhao, G. (2015). The identification of loci for immune traits in chickens using a genome-wide association study. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0117269. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117269

Abstract

Livestock farming, especially poultry, faces considerable social and environmental pressures, particularly concerning animal welfare and the sustainability of farming practices. Furthermore, chronic and emerging diseases can result in significant economic losses. Thus, improving the robustness and resistance of animals to pathogens is becoming a priority. In this context, monitoring the immune response in poultry is crucial to assess their health. Immunophenotyping is a technique that measures immunological parameters after an immune challenge, such as vaccination or infection. It can also provide parameters that indicate the immunocompetence of the animals in their normal state. Immunocompetence can be assessed by measuring resistance or tolerance to a specific pathogen or by analysing a panel of immune parameters. Some measurements are taken directly from blood cells and plasma, to determine the composition of blood cells, antibody levels (total, natural, or specific), plasma proteins, and enzymatic and bactericidal activities. Other parameters, measurable by ex vivo stimulation, assess phagocytosis capacity, response to whole blood stimulation, or T lymphocyte reactivity. Understanding the immune parameters that are correlated to protection during vaccination or infection, and that characterize the immunocompetence of an animal is essential. Integrating knowledge about the parameters that control the immune response and the trade-offs that may exist with other important traits such as performance, stress, and animal welfare is also crucial if they are to be exploited for the genetic improvement of poultry. Exploiting the natural variability of immune characteristics to improve the immunocompetence of animals genetically could be a promising approach, integrated in a complementary way with current strategies such as vaccination to promote sustainable breeding.

Attachments

No supporting information for this article##plugins.generic.statArticle.title##

Views: 1841

Views: 1841

Downloads

PDF: 161

PDF: 161

XML: 20

XML: 20