Enterococcus cecorum, an opportunistic poultry pathogen: deeper understanding for better farm control (Full text available in English)

Enterococcus cecorum has become a major pathogen of poultry worldwide. This bacterium causes locomotor disorders that lead to mortality, increased use of antibiotics and economic losses, particularly in fast-growing broiler farms. This article summarises current epidemiological, zootechnical and basic knowledge with a view to improving disease control and prevention on farms.

Introduction

Diseases affecting poultry typically have multiple causes, including interactions between environmental conditions, genetics, husbandry practices, and the immune status or susceptibility of the animals. In the last five decades, broiler growth rate has increased fivefold between 29 and 35 days of age (Zuidhof et al., 2014). This rapid increase in body mass exerts mechanical stress on the birds' skeletal systems, facilitating invasion and colonisation of joints by opportunistic bacteria. Such bone infections are most often associated with Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli or Enterococcus cecorum (Wideman, 2016; Wijesurendra et al., 2017). Over the last fifteen years, locomotor pathologies caused by E. cecorum have gradually reached a worrying level in broiler farms, affecting both animal health and welfare.

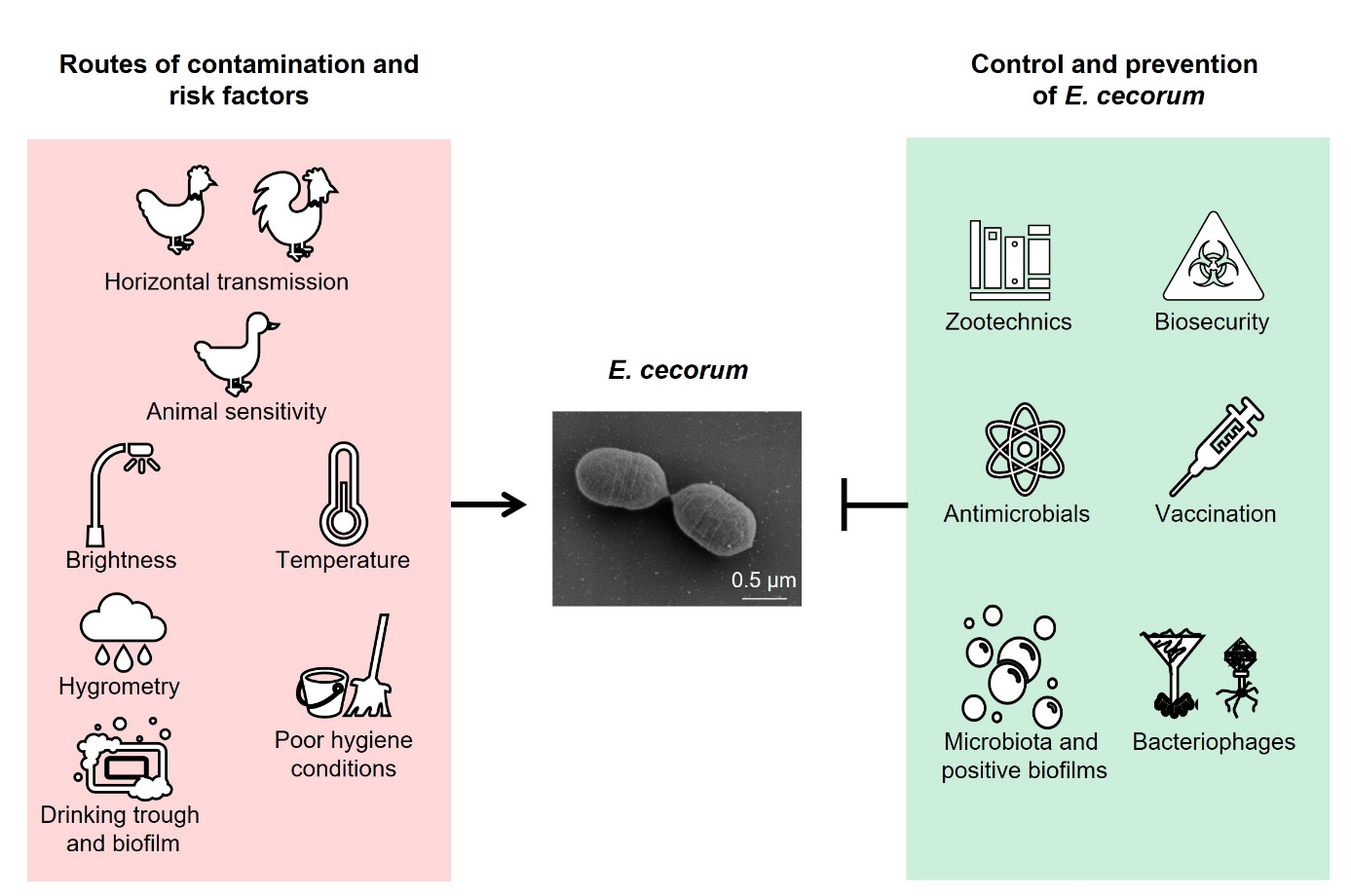

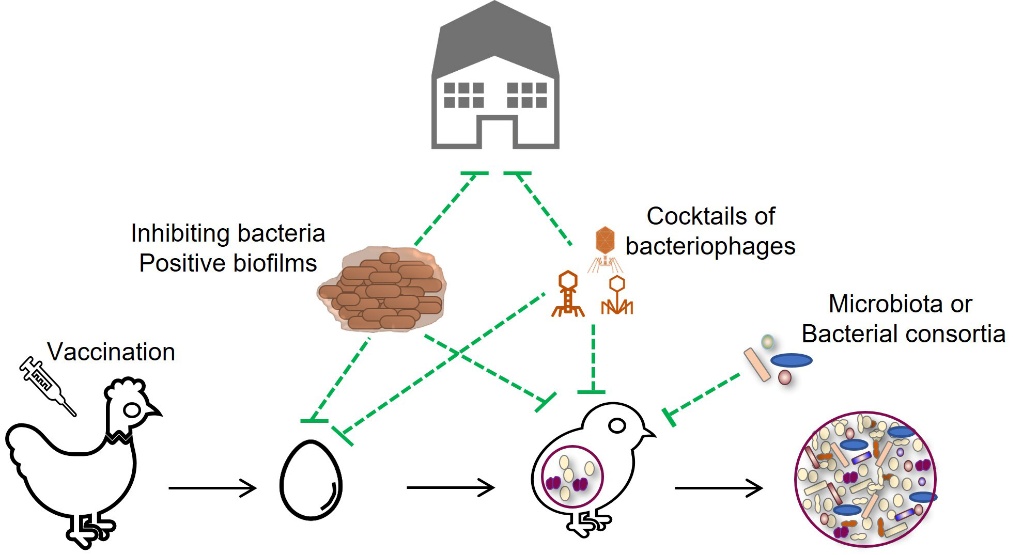

This review attempts to establish a link between current physiological and molecular knowledge of E. cecorum and pathology on farms. It also looks at possible modes of transmission, detection methods and current treatments, as well as preventive zootechnical and biosecurity measures to contain the spread of this bacterium within and between farms. Lastly, it discusses strategies of research and development for controlling this pathogen on farms (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Possible routes of contamination by E. cecorum and preventive measures.

1. An opportunistic pathogen in broiler farming

1.1 E. cecorum, a commensal bacterial agent of the intestinal tract of poultry

E. cecorum was first described in 1983 in Belgium, where it was isolated from the caecal contents of a dead chicken, under the name Streptococcus cecorum (Devriese et al., 1983). In 1989, it was reclassified within the Enterococcus genus, which includes more than 75 species of ubiquitous bacteria found in the intestinal microbiota of terrestrial animals, including birds (Parks et al., 2020; Schwartzman et al., 2024).

E. cecorum is a Gram-positive cocci-shaped facultative anaerobic and non-spore-forming bacterium (Jung et al., 2018). It is a commensal bacterium in the intestinal microbiota of poultry, particularly chickens (Devriese et al., 1991b). It is also found in the intestinal tract of other animals such as pigs, cattle, horses, ducks and turkeys (Devriese et al., 1991a; Scupham et al., 2008). E. cecorum has the ability to form biofilms on inert surfaces (Grund et al., 2022; Laurentie et al., 2023a), and is an opportunistic agent causing locomotor disorders in poultry (Jung et al., 2018).

1.2. Clinical signs

E. cecorum pathologies are primarily observed in chickens, although cases have also been reported in other poultry species, such as ducks and turkeys (Dolka et al., 2017; Souillard et al., 2022). The signs of the disease include reduced feed consumption, uneven growth, dehydration and increased mortality ranging from 7 to over 10% (Robbins et al., 2012; Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014). An initial septicaemic phase results in lesions of pericarditis, fibrinous perihepatitis and splenomegaly (Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014). Locomotor disorders and lameness most often appear from three to four weeks of age (Stalker et al., 2010; Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014; Borst et al., 2017). The characteristic clinical sign of locomotor pathology in chickens infected with E. cecorum is birds sitting on their hocks (Jung et al., 2018). Typical of enterococcal spondyloarthritis, this sign results from paralysis caused by the development of an inflammatory lesion in the free thoracic vertebra that compresses the spinal cord (Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014). Arthritis, synovitis and necrosis of the femoral heads have also been observed (Stalker et al., 2010; Borst et al., 2012; Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014). Sepsis and bone lesions result in carcass condemnations at slaughter, with rates reaching up to 9.75%. (Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014). Diseases caused by E. cecorum thus result in significant economic losses on farms.

1.3 History and epidemiology

E. cecorum emerged as a poultry pathogen in the early 2000s. The first cases were reported in Scotland (Wood et al., 2002) and the Netherlands (Devriese et al., 2002), then more widely in other European countries (Makrai et al., 2011; Szeleszczuk et al., 2013; AMCRA, 2021) and North America (Stalker et al., 2010; Borst et al., 2012). In France, there has been a noticeable increase in pathologies associated with E. cecorum in poultry over the last 15 years. Data from RNOEA, the French poultry epidemiological surveillance network, shows a significant emergence of this bacterium. In 2006, Enterococcus represented only 0.4% of all pathogens reported, whereas this proportion had risen to 12.9% by 2020 (Souillard et al., 2022). Most diseases associated with Enterococcus were found in broilers. Furthermore, locomotor disorders, which were caused by E. cecorum, increased from 6% in 2017 to 14.8% in 2022. Among all transmitted pathogens in broilers reported to the network in 2022 for this production (n = 4 289), E. cecorum was second only to E. coli, accounting for 16.3% and 63.6%, respectively. This emergence can be explained in part by increased vigilance on the part of veterinarians in the field and improvements in laboratory diagnostic methods since the 2010s (Dolka et al., 2017; Karunarathna et al., 2017; Suyemoto et al., 2017; Tessin et al., 2024). However, E. cecorum pathology is now a major disease in broiler production worldwide.

1.4. Pathogenesis

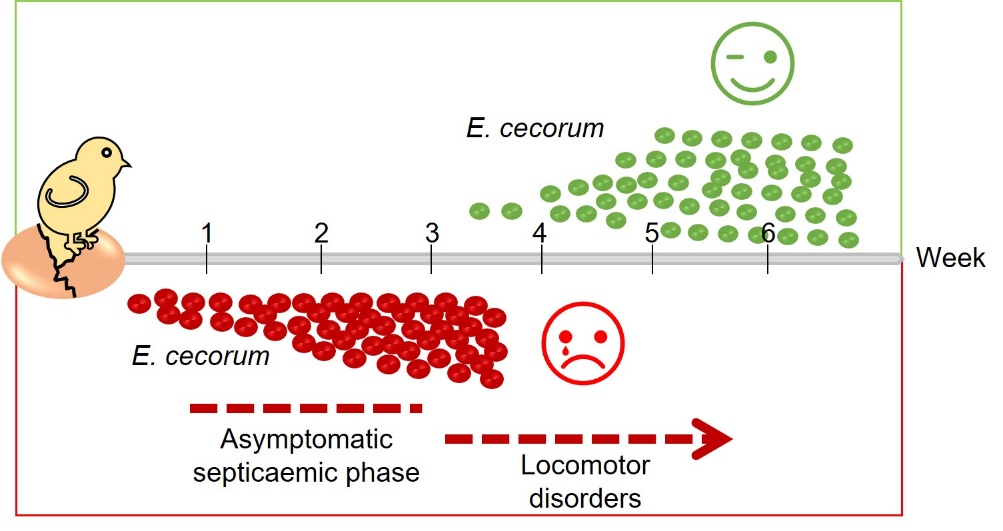

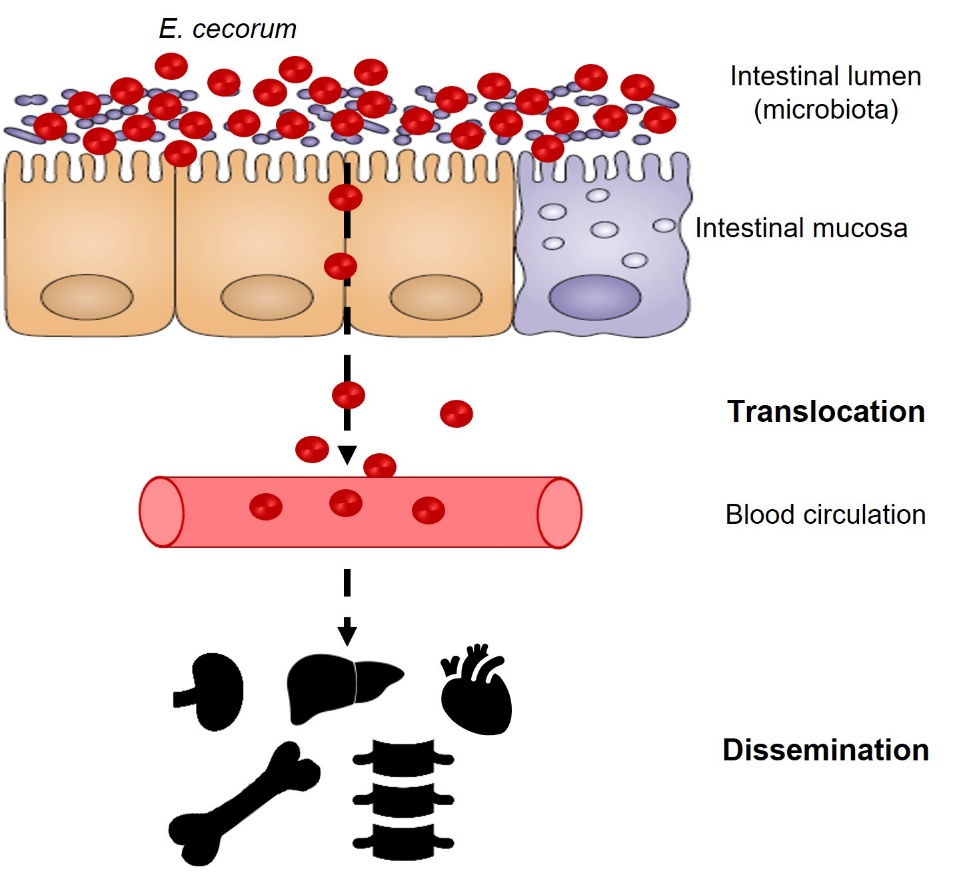

Clinical strains of E. cecorum appear to be adapted to colonise the gut from the first days of life, whereas commensal isolates do not appear to colonise the gut at a detectable level until the third week of life (Devriese et al., 1991b; Borst et al., 2017) (Figure 2). Indeed, Borst et al. (2017) showed that in farms with clinical episodes of E. cecorum, the bacterium was detected in the intestinal contents as early as the first week of life in 60% of animals. Conversely, E. cecorum was only detectable from the third week of life in 30% of animals in farms without an infectious episode (Borst et al., 2017). According to the current model, the bacterium enters the bloodstream after colonising the intestine and crossing the intestinal mucosa, which explains why it is detected in organs such as the heart, liver and spleen during the early phase of infection (Figure 3). During this septic phase, E. cecorum is thought to spread to skeletal sites, including the thoracic vertebrae, femoral heads and joints, causing inflammation that leads to lameness and paralysis (Borst et al., 2017). The resistance of clinical isolates of E. cecorum to high concentrations of lysozyme could give them an ecological advantage in the early colonisation of chicks (Manders et al., 2024).

Figure 2. Temporal association between the presence of E. cecorum and clinical signs.

Figure 3: Model of E. cecorum infection in chicks.

1.5. Virulence or opportunism

Several molecular epidemiology studies have used pulsed-field electrophoresis (PFGE) to profile commensal and clinical isolates. Results from the USA, Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Poland have shown that commensal isolates are more diverse than clinical isolates, suggesting the evolution of specific clones with higher pathogenic potential (Kense & Landman, 2011; Boerlin et al, 2012; Borst et al., 2012; Robbins et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2023). Genomic analysis of approximately one hundred avian clinical isolates collected in France between 2007 and 2017 confirmed the clonal nature of avian clinical isolates, which are part of a phylogenetic clade found in the United States and Europe (Laurentie et al., 2023a). More recently, a phylogenetic study of about thirty clinical strains from American farms, isolated from septicaemic animals during the first three weeks of life, seems to raise doubts concerning the clonal nature of the clinical isolates responsible for lameness by revealing a septicaemia-associated clone (Rhoads et al., 2024). Mutations identified in seven genes conserved across all strains appear to reflect host adaptation. At present, we cannot rule out the emergence of a new clone responsible for septicaemia. It would be interesting to assess the infectious potential of these strains and determine their ability to induce lameness.

Despite these advances, distinguishing between clinical and commensal strains remains a challenge. The identification of genes preferentially found in clinical isolates could help to distinguish them from non-clinical isolates (Borst et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2023; Laurentie et al., 2023a). For example, the capsule protects bacteria from phagocytosis and the prevalence of certain capsule genes in clinical isolates suggests a role in virulence (Huang et al., 2023; Laurentie et al., 2023a). Other genes more frequently found in the genomes of clinical isolates may contribute to virulence by encoding functions that are likely to provide alternative metabolic capacities for survival and reproduction within the host (Borst et al., 2015; Laurentie et al., 2023a; Rhoads et al., 2024). Currently, there is no infection model to distinguish clinical from non-clinical isolates or to study the impact of specific genes on virulence. The lethality test on embryonated chicken eggs has shown significant variations in mortality and lesions between isolates, but its relevance and reliability need to be consolidated due to disparities between studies (Borst et al., 2014; Ekesi et al., 2021; Dolka et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023; Laurentie et al., 2023a). Oral inoculation in two-week-old birds was found to be more effective than intravenous inoculation or air sacs in reproducing spinal lesions, as evidenced by macroscopic and microscopic examination for spinal lesions (Martin et al., 2011). The team of A. Jung's team in Germany described an oral infection model in day-old chicks that was as close as possible to field conditions. Although this model reproduced the septic phase and late clinical signs in up to 20% of infected birds, only one of the two clinical isolates tested proved virulent (Schreier et al., 2021). Recently, an in ovo infection model at 18 days of embryonic development detected the bacterium in the femoral head and free thoracic vertebra in over 60% of birds (Arango et al., 2023). However, as the presence of E. cecorum was not tested in the intestinal microbiota, it is not possible to determine whether the bone infection resulted from the initial infection or from early intestinal colonisation. Distinguishing between commensal and clinical isolates of E. cecorum remains challenging due to the lack of reliable molecular or phenotypic tools.

1.6. Antibiotic resistance

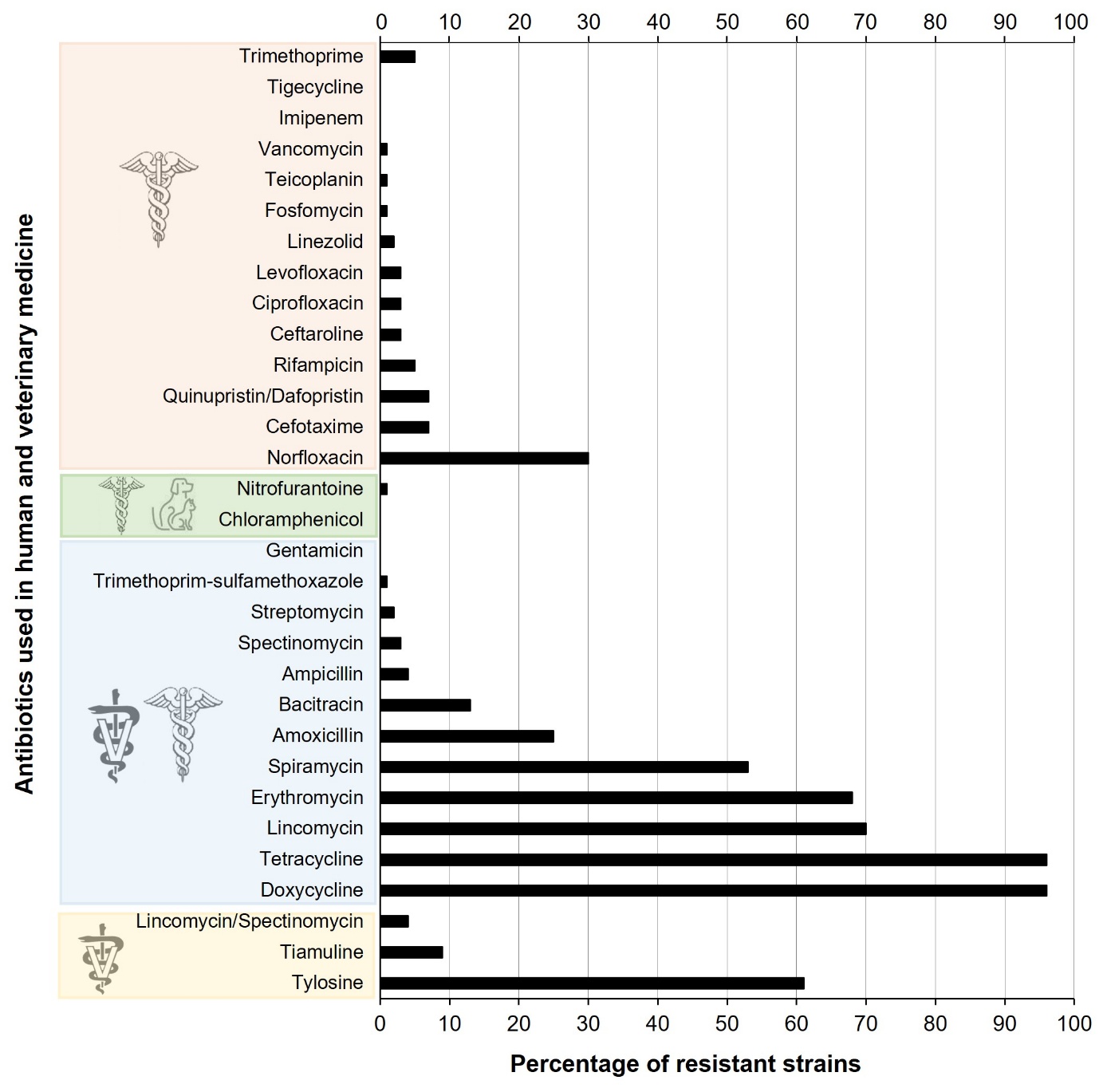

Several North American and European studies show a high prevalence of tetracycline resistance (>70%) in clinical and non-clinical isolates of E. cecorum, while macrolide resistance (erythromycin, spiramycin and tylosin) is more common in clinical isolates (Jung et al., 2018; Laurentie et al., 2023b). Conversely, lincomycin resistance is more prevalent in isolates of non-clinical origin, which have more extensive antibiotic resistance profiles than clinical isolates (Boerlin et al., 2012; Borst et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2015; Laurentie et al., 2023b). In France, 43.3% of isolates appear to be resistant to more than three classes of antibiotics, compared to 1.4% of isolates sensitive to the twenty or so molecules tested (Laurentie et al., 2023b). Nevertheless, the majority of isolates of clinical origin remain sensitive to the antimicrobials authorised for use in poultry. Similarly, it is reassuring to note that resistance to antimicrobials of critical importance in human medicine such as vancomycin, gentamicin, tigecycline, linezolid and daptomycin is not widespread in E. cecorum (Laurentie et al., 2023b) (Figure 4). These trends are validated by the distribution of resistance genes in genomes (Sharma et al., 2020; Laurentie et al., 2023b; Huang et al., 2024). Tetracycline resistance genes (tet(M) and tet(L)), macrolide resistance genes (erm(B)) and, to a lesser extent, bacitracin resistance genes (bcr operon) are the most common. Chromosomal mutations in the gyrA and parC genes explain more than 65% of quinolone resistance (Laurentie et al., 2023b) and a pbp2 gene could contribute to ampicillin resistance (Huang et al., 2024). While no plasmids have been described in E. cecorum, the most common resistance genes are carried by complex genetic elements that have all the characteristics of mobile elements.

Figure 4. Distribution of antibiotic resistance in E. cecorum strains.

1.7 Predisposing factors in animals

Animal sensitivity can influence the development of locomotor pathologies caused by E. cecorum. Increased body weight in poultry can lead to mechanical stresses on the locomotor system, leading to bone lesions with colonisation by various opportunistic bacteria (Wideman, 2016). Abnormal development of the locomotor system, such as early osteochondrosis lesions, could also predispose poultry to E. cecorum infections (Borst et al., 2017). However, no comparative studies on predisposition to infection as a function of lineage growth rate have been published thus far. A reduction in animal immunity or concomitant infections could also play a role in the development of the disease. The hypothesis of an alteration in the intestinal barrier favouring translocation of the bacteria has been raised in relation to intercurrent infections (E. coli or Eimeria parasites) or changes in the microbiota (Borst et al., 2017). However, co-infection of E. cecorum with a mixture of three Eimeria spp. species, including Eimeria tenella, has recently been associated with a decrease in the incidence of E. cecorum bacteraemia and the severity of spondyloarthritis (Borst et al., 2019). This result could be explained by a change in the intestinal microbiota, especially as a strain of E. tenella has been shown to contribute to the diversification of the caecal microbiota and the strengthening of the intestinal mucosa (Zhou et al., 2020). Heat stress, which causes changes in the composition of the intestinal microbiota, could also alter the integrity of the intestinal mucosa and promote E. cecorum translocation (Schreier et al., 2022b). While none of these factors is sufficient to trigger infection by E. cecorum, their combination could contribute to additive risk.

2. Which transmission route(s)?

2.1. Vertical transmission

How poultry are contaminated and how E. cecorum is introduced into farms is still poorly understood. The possibility of vertical transmission has been studied, with inconclusive results. Indeed, genomic and metabolomic patterns of E. cecorum from breeding birds and the clinical isolates from their offspring have not shown any correlation and the bacterium has not been found in the hatchery environment (Kense & Landman, 2011; Robbins et al., 2012). Furthermore, experimental infection of breeder chickens failed to detect the presence of the bacterium in eggs (Thofner & Christensen, 2016). Although vertical transmission of Enterococcus species has been demonstrated, this does not seem to involve E. cecorum (Shterzer et al., 2023). Current research is limited, and further investigation is required to explore the possibility of vertical transmission of the bacterium in broiler farms.

2.2. Horizontal transmission

Horizontal transmission can result from direct contact between animals or indirectly, via contaminated equipment. Birds excrete E. cecorum in their droppings, and can thus become infected via the faecal-oral route (Borst et al., 2017). In addition, the bacterium could be transmitted by inhalation of contaminated dust from farm houses (Jung & Rautenschlein, 2014). The frequency of recurrences on farms, as reported in Belgium (Herdt et al., 2008) and France (Potier et al, 2024) suggests that there may be biological reservoirs such as darkling beetles, rodents, etc., or environmental reservoirs in areas of persistence difficult to clean and disinfect, such as feeding lines, ventilation and heating systems, as well as drinking pipettes, feeders and cracks in the floor (Luyckx et al., 2015; Tessin et al., 2024). A recent study shows a higher prevalence in summer (Dunnam et al., 2023). The bacterium survives on different substrates (litter, dust, plastic) at different temperatures and humidity levels, particularly on litter at 15°C and 32% humidity (Grund et al., 2021). In this study, the two clinical strains showed prolonged survival compared with the commensal strain. Although E. cecorum has not been isolated from the environment of farms affected by the bacterium (Robbins et al., 2012; Grund et al., 2022), the presence of DNA from the 16S gene of E. cecorum was detected in the drinking systems (Grund et al., 2022) and also after cleaning in the air admission circuit and the anteroom (Tessin et al., 2024). Further research is therefore needed to provide a better understanding of the E. cecorum contamination routes and of persistence areas on the farms.

3. Diagnosis and treatment

3.1. Diagnosis of the disease

Lameness, with potential paralysis characterised by a "sitting on the hocks" position, increased mortality and arthritic lesions, necrosis of the femoral heads or spondyloarthritis are clinical signs suggestive of E. cecorum infection. Other bacterial agents, such as E. coli, can also cause these clinical signs and lesions in poultry. Bacteriological analysis is therefore necessary to confirm the diagnosis of E. cecorum infection. Isolation of E. cecorum from lesions is classically performed in the presence of CO2 (5%) on a blood agar medium to which colistin and nalidixic acid may be added to inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria. Identification is currently carried out using MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionisation time-of-flight) mass spectrometry, which is easier and more reliable than PCR identification (Karunarathna et al., 2017). This development has certainly contributed to the increase in the identification of Enterococcus and E. cecorum species in avian pathology since 2006 (Souillard et al., 2022).

3.2. Treatment

Antibiotic susceptibility tests for E. cecorum are performed according to E. faecalis or E. faecium standards (Borst et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2015; Dolka et al., 2016). Epidemiological cut-offs (ECOFFs) have been provisionally established for about twenty antibiotics in E. cecorum (Laurentie et al., 2023b). These require independent validation by other laboratories on a larger collection of strains before they can be adjusted and approved by the European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). A better assessment of the antibiotic resistance of strains should help to improve the effectiveness of treatments and thus better control the use of antibiotics in livestock farming.

Currently, if an E. cecorum infection is diagnosed, early antibiotic treatment must be implemented rapidly to limit the spread of infection within a poultry flock. Treatment is ineffective on birds already exhibiting lesions and paralysis. If the choice of antibiotic is based on the results of the antibiogram, penicillin derivatives, in particular amoxicillin, are commonly used (Devriese et al., 2002; Herdt et al., 2008; Jung et al., 2018), sometimes requiring repeated treatments within a flock. However, due to the frequent recurrence of the disease on certain farms and its severity, antibiotic treatment during the first week of life has been suggested to control the disease, using amoxicillin and/or tylosin (Herdt et al., 2008) or lincospectin (Schreier et al., 2022a). In accordance with Regulation (EU) no 2019/6, which regulates the use of antibiotics in animals to reduce antibiotic resistance, the use of antimicrobial medicinal products in a poultry flock for prophylactic purposes must remain exceptional "when the risk of infection or infectious disease is very high and the consequences are likely to be serious" (Article 107 of Regulation (EU) no 2019/6). It is essential to control the circumstances under which E. cecorum infections occur, in order to implement preventive measures based on farm management and sanitary measures.

4. Possible measures to implement on poultry farms to prevent the spread of infection

4.1. Farm management to limit risk

Various zootechnical measures have been proposed to limit the risk of E. cecorum pathologies (Figure 1). Among these, adjusting lighting programmes to slow animal growth during the first few weeks of life could limit the impact of the disease (Jung et al., 2018). Insufficient darkness in buildings has been identified as a risk practice. Less than six hours of light cut-off at ten days of age would constitute an aggravating practice (Remiot et al., 2019). In addition, increasing skeletal strength and limiting mechanical stress on the musculoskeletal system could help reduce the risk of bone lesions and E. cecorum infections. Optimising early rearing conditions with good litter quality, sufficient air ventilation and temperature control could also limit the risk of disease (Remiot et al., 2019; Schreier et al., 2022b). Disease prevention also involves preventing digestive disorders and intercurrent infections that could promote infection, such as coccidiosis (Borst et al., 2017) or immunosuppressive diseases such as Gumboro disease (Sary et al., 2018). Finally, the frequency of recurrences suggests that E. cecorum persists in the environment, including farm buildings, even though the presence of viable bacteria has not been demonstrated due to the lack of a selective culture medium (Tessin et al., 2024). The presence of E. cecorum in watering systems is still a matter of debate (Grund et al., 2022; Tessin et al., 2024). It has also been shown that inadequate cleaning and disinfection could be a risk factor (Remiot et al., 2019) and that E. cecorum DNA could be detected after the cleaning/disinfection of houses, in the anteroom, pipes and air circuits (Tessin et al., 2024). The potential environmental persistence of E. cecorum, evidenced by detection even after cleaning and disinfection, underscores the need to reinforce biosecurity (compliance with the anteroom and protocols for changing clothes and washing hands, disinfection of equipment) and hygiene practices (disinfection of houses and water pipes) to better prevent the disease.

An alternative way of preventing the proliferation of undesirable bacteria on farms is to use mixtures of bacteria to form a protective biofilm on buildings before chick arrival (Guéneau et al., 2022a) (Figure 5). The application of a mixture of Bacillus spp. and Pediococcus spp. strains could limit the development of enterobacteria and enterococci (Guéneau et al., 2022b). This measure could contribute to better environmental hygiene management for birds. The rotation of disinfection agents (biocides) and bacterial biofilms between two flocks should reduce the risk of emergence of resistant strains.

4.2. Strategies for prevention

Vaccination of poultry could be a valuable tool for controlling E. cecorum diseases on farms (Figure 1). However, there is currently no commercial vaccine available, although research is ongoing. In particular, it has been shown that vaccination of breeding hens with a polyvalent inactivated vaccine against E. cecorum did not prevent the disease in chicks (Borst et al., 2019). Serological ELISA methods have yet to be developed to assess serological responses to E. cecorum infection and vaccination in breeding hens and chicks (Jung & Rautenschlein, 2020; Silberborth et al., 2024).

Modern poultry farming practices disrupt the natural vertical transmission of chicken microbiota by preventing contact between hens and chicks. As a result, the animals acquire a poorly diverse and ill-defined microbiota from their environment. This early disruption of colonisation can lead to an imbalance in the microbiota, or dysbiosis, and/or a lack of maturation of the intestinal mucosa and immune system, which can affect production performance and resistance to pathogens (Rubio, 2019; Rychlik, 2020). The colonisation of the initial microbiota is essential for inducing a good immune response (Rodrigues et al., 2021). While the role of the intestinal microbiota in the infectious potential of E. cecorum has not been established, the intestinal detection of clinical isolates in the first two weeks and the efficacy of early treatment with lincospectin in preventing infection suggest a window of opportunity for intervention to promote the ecological barrier of the microbiota and the mucosal barrier (Hankel et al., 2021; Schreier et al., 2022a) (Figure 5). Among the various strategies considered in livestock farming to stimulate the ecological barrier of the intestinal microbiota, the use of probiotic strains such as Bacillus for their antagonistic activity is one of the oldest (Cutting, 2011). Various Bacillus strains have been isolated for their inhibitory activity against E. cecorum (Medina Fernández et al., 2019; Penaloza-Vazquez et al., 2019; Sandvang et al., 2024). Their efficacy depends on the probiotic strains and the E. cecorum isolate targeted. Further work is needed to study their efficacy in vivo and characterise the inhibiting molecules. Understanding the role of the microbiota in the pathogenesis of E. cecorum is a prerequisite for developing new preventive strategies that could be based on the transfer of healthy microbiota or the implantation of consortia of avian probiotic or commensal bacteria.

Cocktails of bacteriophages are also available in some European countries and North America as food supplements or probiotics (Bacteriophage.news., n.d.; Gigante & Atterbury, 2019; Abd-El Wahab et al., 2023). Phages lyse bacteria with the advantage of having a limited host spectrum, reducing collateral effects in the targeted microbiota. Their use in cocktails also reduces the risk of resistant strains emerging. To date, virulent phage specific to E. cecorum have not been described, but this approach is worth considering because of the genetic similarity of clinical strains. Administration of these phages during the first two weeks of rearing could help prevent or delay early colonisation of infectious isolates. However, whatever alternative methods are considered, it is essential to assess their environmental consequences on human and animal health, environmental microbial ecology and the risk of emergence of resistant strains.

Figure 5. Research strategies to prevent the proliferation of E. cecorum in the poultry houses and the chick environment.

Conclusion

Like many opportunistic pathogens, the virulence of E. cecorum is multifactorial. Its relatively recent emergence suggests a direct correlation with changes in rearing practices, which may have led to the selection of a clone capable of infecting fast-growing broilers chickens. It is essential to improve our zootechnical, epidemiological and fundamental knowledge of the physiology and pathogenesis of E. cecorum in order to implement effective measures for the prevention and control of the disease. To effectively manage this pathogen, it is essential to develop rapid diagnostic methods capable of distinguishing clinical from non-clinical strains, thus clarifying routes of transmission and farm contamination. The development of a robust animal model reproducing at least the early phase of infection is necessary to understand the interaction of E. cecorum with the microbiota and its host, using global approaches (metagenomics, metabolomics and proteomics). This knowledge should enable preventive strategies to be defined to limit the use of antibiotics and the associated selection pressure, as well as reducing the clinical impact, animal suffering and economic losses on farms.

Authors' contributions

All the authors took part in writing the article, coordinated and supervised by Pascale Serror.

Acknowledgements

J. Laurentie received a grant from ANSES and INRAE. The work behind this synthesis was supported by INRAE's GISA metaprogramme (CecoType project), the French Ministry of Agriculture (DGAL) through the Ecoantibio2 programme number 2018-180 and INRAE's Microbiology and Food Chain Department (Mica).

This article was first translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator. The authors are grateful to Sean P. Kennedy for English language editing.

Notes

- 1. This article was presented at the 15th Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie gras, 20-21 March 2024 in Tours (Souillard et al., 2024).

References

- Abd-El Wahab, A., Basiouni, S., El-Seedi, H. R., Ahmed, M. F. E., Bielke, L. R., Hargis, B., Tellez-Isaias, G., Eisenreich, W., Lehnherr, H., Kittler, S., Shehata, A. A., & Visscher, C. (2023). An overview of the use of bacteriophages in the poultry industry: Successes, challenges, and possibilities for overcoming breakdowns. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1136638. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1136638

- AMCRA. (2021). Mesures pour un bon usage des antibiotiques lors d'un traitement de groupe chez la volaille (Rapport). Centre de connaissances antimicrobial consumption and resistance in animals. https://amcra.be/swfiles/files/Advies_Groepsbehandelingen_Pluimvee_Finaal_FR_goedgekeurd-RvB_finaal.pdf

- Arango, M., Forga, A., Liu, J., Zhang, G., Gray, L., Moore, R., Coles, M., Atencio, A., Trujillo, C., Latorre, J. D., Tellez-Isaias, G., Hargis, B., & Graham, D. (2023). Characterizing the impact of Enterococcus cecorum infection during late embryogenesis on disease progression, cecal microbiome composition, and early performance in broiler chickens. Poultry Science, 102(11), 103059. doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.103059

- Bacteriophage.news. (s. d.). Updated bacteriophage product database [Base de données]. Retrieved from https://www.bacteriophage.news/phage-products/

- Boerlin, P., Nicholson, V., Brash, M., Slavic, D., Boyen, F., Sanei, B., & Butaye, P. (2012). Diversity of Enterococcus cecorum from chickens. Veterinary Microbiology, 157(3-4), 405-411. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.01.001

- Borst, L. B., Suyemoto, M. M., Robbins, K. M., Lyman, R. L., Martin, M. P., & Barnes, H. J. (2012). Molecular epidemiology of Enterococcus cecorum isolates recovered from enterococcal spondylitis outbreaks in the southeastern United States. Avian Pathology, 41(5), 479-485. doi:10.1080/03079457.2012.718070

- Borst, L. B., Suyemoto, M. M., Keelara, S., Dunningan, S. E., Guy, J. S., & Barnes, H. J. (2014). A chicken embryo lethality assay for pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum. Avian Diseases, 58(2), 244-248. doi:10.1637/10687-101113-Reg.1

- Borst, L. B., Suyemoto, M. M., Scholl, E. H., Fuller, F. J., & Barnes, H. J. (2015). Comparative genomic analysis identifies divergent genomic features of pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum including a type IC CRISPR-cas system, a capsule locus, an epa-like locus, and putative host tissue binding proteins. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0121294. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121294

- Borst, L. B., Suyemoto, M. M., Sarsour, A. H., Harris, M. C., Martin, M. P., Strickland, J. D., Oviedo, E. O., & Barnes, H. J. (2017). Pathogenesis of enterococcal spondylitis caused by Enterococcus cecorum in broiler chickens. Veterinary Pathology, 54(1), 61-73. doi:10.1177/0300985816658098

- Borst, L. B., Suyemoto, M. M., Chen, L. R., & Barnes, H. J. (2019). Vaccination of breeder hens with a polyvalent killed vaccine for pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum does not protect offspring from enterococcal spondylitis. Avian Pathology, 48(1), 17-24. doi:10.1080/03079457.2018.1536819

- Cutting, S. M. (2011). Bacillus probiotics. Food Microbiology, 28(2), 214-220. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.007

- Devriese, L. A., Dutta, G. N., Farrow, J. A. E., Van De Kerckhove, A., & Phillips, B. A. (1983). Streptococcus cecorum, a new species isolated from chickens. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 33(4), 772-776. doi:10.1099/00207713-33-4-772

- Devriese, L. A., Ceyssens, K., & Haesebrouck, F. (1991a). Characteristics of Enterococcus cecorum strains from the intestines of different animal species. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 12(4), 137-139. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.1991.tb00524.x

- Devriese, L. A., Hommez, J., Wijfels, R., & Haesebrouck, F. (1991b). Composition of the enterococcal and streptococcal intestinal flora of poultry. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 71(1), 46-50. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb04661.x

- Devriese, L. A., Cauwerts, K., Hermans, K., & Wood, A. M. (2002). Enterococcus cecorum septicemia as a cause of bone and joint lesions resulting in lameness in broiler chickens. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift, 71(3), 219-221. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0036558345&partnerID=40&md5=f1dea35caef06ce66a8742ba10a7bbef

- Dolka, B., Chrobak-Chmiel, D., Makrai, L., & Szeleszczuk, P. (2016). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Enterococcus cecorum strains associated with infections in poultry. BMC Veterinary Research, 12(1), 129. doi:10.1186/s12917-016-0761-1

- Dolka, B., Chrobak-Chmiel, D., Czopowicz, M., & Szeleszczuk, P. (2017). Characterization of pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum from different poultry groups: Broiler chickens, layers, turkeys, and waterfowl. PLoS ONE, 12(9), e0185199. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185199

- Dolka, B., Czopowicz, M., Dolka, I., & Szeleszczuk, P. (2022). Chicken embryo lethality assay for determining the lethal dose, tissue distribution and pathogenicity of clinical Enterococcus cecorum isolates from poultry. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 10675. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-14900-9

- Dunnam, G., Thornton, J. K., & Pulido-Landinez, M. (2023). Characterization of an Emerging Enterococcus cecorum outbreak causing severe systemic disease with concurrent leg problems in a broiler integrator in the Southern United States. Avian Diseases, 67(2), 137-144. doi:10.1637/aviandiseases-D-22-00085

- Ekesi, N. S., Hasan, A., Parveen, A., Shwani, A., & Rhoads, D. D. (2021). Embryo lethality assay as a tool for assessing virulence of isolates from bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis in broilers. Poultry Science, 100(11), 101455. doi:10.1016/j.psj.2021.101455

- Gigante, A., & Atterbury, R. J. (2019). Veterinary use of bacteriophage therapy in intensively-reared livestock. Virology Journal, 16(1), 155. doi:10.1186/s12985-019-1260-3

- Grund, A., Rautenschlein, S., & Jung, A. (2021). Tenacity of Enterococcus cecorum at different environmental conditions. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 130(5), 1494-1507. doi:10.1111/jam.14899

- Grund, A., Rautenschlein, S., & Jung, A. (2022). Detection of Enterococcus cecorum in the drinking system of broiler chickens and examination of its potential to form biofilms. European Poultry Science, 86. doi:10.1399/eps.2022.346

- Guéneau, V., Plateau-Gonthier, J., Arnaud, L., Piard, J. C., Castex, M., & Briandet, R. (2022a). Positive biofilms to guide surface microbial ecology in livestock buildings. Biofilm, 4, 100075. doi:10.1016/j.bioflm.2022.100075

- Guéneau, V., Rodiles, A., Frayssinet, B., Piard, J. C., Castex, M., Plateau-Gonthier, J., & Briandet, R. (2022b). Positive biofilms to control surface-associated microbial communities in a broiler chicken production system - a field study. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, 981747. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.981747

- Hankel, J., Bodmann, B., Todte, M., Galvez, E., Strowig, T., Radko, D., Antakli, A., & Visscher, C. (2021). Comparison of chicken cecal microbiota after metaphylactic treatment or following administration of feed additives in a broiler farm with enterococcal spondylitis history. Pathogens, 10(8), 1068. doi:10.3390/pathogens10081068

- Herdt, P., Defoort, P., Steelant, J., Swam, H., Tanghe, L., Goethem, S., & Vanrobaeys, M. (2008). Enterococcus cecorum osteomyelitis and arthritis in broiler chickens. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift, 78(1), 44-48. doi:10.21825/vdt.87495

- Huang, Y., Eeckhaut, V., Goossens, E., Rasschaert, G., Van Erum, J., Roovers, G., Ducatelle, R., Antonissen, G., & Van Immerseel, F. (2023). Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis related Enterococcus cecorum isolates are genetically distinct from the commensal population and are more virulent in an embryo mortality model. Veterinary research, 54(1), 13. doi:10.1186/s13567-023-01146-0

- Huang, Y., Boyen, F., Antonissen, G., Vereecke, N., & Van Immerseel, F. (2024). The Genetic landscape of antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterococcus cecorum broiler isolates. Antibiotics, 13(5), 409. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13050409

- Jackson, C. R., Kariyawasam, S., Borst, L. B., Frye, J. G., Barrett, J. B., Hiott, L. M., & Woodley, T. A. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance, virulence determinants and genetic profiles of clinical and nonclinical Enterococcus cecorum from poultry. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 60(2), 111-119. doi:10.1111/lam.12374

- Jung, A., & Rautenschlein, S. (2014). Comprehensive report of an Enterococcus cecorum infection in a broiler flock in Northern Germany. BMC Veterinary Research, 10, 311. doi:10.1186/s12917-014-0311-7

- Jung, A., Chen, L. R., Suyemoto, M. M., Barnes, H. J., & Borst, L. B. (2018). A review of Enterococcus cecorum infection in poultry. Avian Diseases, 62(3), 261-271. doi:10.1637/11825-030618-Review.1

- Jung, A., & Rautenschlein, S. (2020). Development of an in-house ELISA for detection of antibodies against Enterococcus cecorum in Pekin ducks. Avian Pathology, 49(4), 355-360. doi:10.1080/03079457.2020.1753653

- Karunarathna, R., Popowich, S., Wawryk, M., Chow-Lockerbie, B., Ahmed, K. A., Yu, C., Liu, M., Goonewardene, K., Gunawardana, T., Kurukulasuriya, S., Gupta, A., Willson, P., Ambrose, N., Ngeleka, M., & Gomis, S. (2017). Increased incidence of enterococcal infection in nonviable broiler chicken embryos in Western Canadian hatcheries as detected by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Avian Diseases, 61(4), 472-480. doi:10.1637/11678-052317-Reg.1

- Kense, M. J., & Landman, W. J. M. (2011). Enterococcus cecorum infections in broiler breeders and their offspring: Molecular epidemiology. Avian Pathology, 40(6), 603-612. doi:10.1080/03079457.2011.619165

- Laurentie, J., Loux, V., Hennequet-Antier, C., Chambellon, E., Deschamps, J., Trotereau, A., Furlan, S., Darrigo, C., Kempf, F., Lao, J., Milhes, M., Roques, C., Quinquis, B., Vandecasteele, C., Boyer, R., Bouchez, O., Repoila, F., Le Guennec, J., Chiapello, H., … Serror, P. (2023a). Comparative genome analysis of Enterococcus cecorum reveals intercontinental spread of a lineage of clinical poultry Isolates. mSphere, 8(2), e0049522. doi:10.1128/msphere.00495-22

- Laurentie, J., Mourand, G., Grippon, P., Furlan, S., Chauvin, C., Jouy, E., Serror, P., & Kempf, I. (2023b). Determination of epidemiological cutoff values for antimicrobial resistance of Enterococcus cecorum. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 61(3), e01445-22. doi:10.1128/jcm.01445-22

- Luyckx, K. Y., Van Weyenberg, S., Dewulf, J., Herman, L., Zoons, J., Vervaet, E., Heyndrickx, M., & De Reu, K. (2015). On-farm comparisons of different cleaning protocols in broiler houses. Poultry Science, 94(8), 1986-1993. doi:10.3382/ps/pev143

- Makrai, L., Nemes, C., Simon, A., Ivanics, É., Dudás, Z., Fodor, L., & Glávits, R. (2011). Association of Enterococcus cecorum with vertebral osteomyelitis and spondylolisthesis in broiler parent chicks. Acta Veterinaria Hungarica, 59(1), 11-21. doi:10.1556/AVet.59.2011.1.2

- Manders, T., Benedictus, L., Spaninks, M., & Matthijs, M. (2024). Enterococcus cecorum lesion strains are less sensitive to the hostile environment of albumen and more resistant to lysozyme compared to cloaca strains. Avian Pathology, 53(2), 106-114. doi:10.1080/03079457.2023.2286985

- Martin, L. T., Martin, M. P., & Barnes, H. J. (2011). Experimental reproduction of enterococcal spondylitis in male broiler breeder chickens. Avian Diseases, 55(2), 273-278. doi:10.1637/9614-121410-Reg.1

- Medina Fernández, S., Cretenet, M., & Bernardeau, M. (2019). In vitro inhibition of avian pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum isolates by probiotic Bacillus strains. Poultry Science, 98(6), 2338-2346. doi:10.3382/ps/pey593

- Parks, D. H., Chuvochina, M., Chaumeil, P. A., Rinke, C., Mussig, A. J., & Hugenholtz, P. (2020). A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nature Biotechnology, 38(9), 1079-1086. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0501-8

- Penaloza-Vazquez, A., Ma, L. M., & Rayas-Duarte, P. (2019). Isolation and characterization of Bacillus spp. strains as potential probiotics for poultry. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 65(10), 762-774. doi:10.1139/cjm-2019-0019

- Potier, P. H., Rigomier, P., Moalic, P. Y., & Bourgeon, F. (2024). Étude préliminaire de la diversité moléculaire d’Enterococcus cecorum dans les élevages bretons [Communication]. 15e Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie Gras, Tours.

- Remiot, P., Panaget, G., Chataigner, E., & Chevalier, D. (2019). Enterococcus cecorum chez le poulet de chair : enquête en élevage pour identifier des pratiques zootechniques à risque [Communication]. 13e Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie Gras, Tours. https://www.itavi.asso.fr/publications/enterococcus-cecorum-chez-le-poulet-de-chair-enquete-en-elevage-pour-identifier-des-pratiques-zootechniques-a-risque?search=Enterococcus%20cecorum%20chez%20&order=score

- Rhoads, D. D., Pummill, J., & Alrubaye, A. A. K. (2024). Molecular genomic analyses of Enterococcus cecorum from sepsis outbreaks in broilers. Microorganisms, 12(2), 250. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12020250

- Robbins, K. M., Suyemoto, M. M., Lyman, R. L., Martin, M. P., Barnes, H. J., & Borst, L. B. (2012). An outbreak and source investigation of enterococcal spondylitis in broilers caused by Enterococcus cecorum. Avian Diseases, 56(4), 768-773. doi:10.1637/10253-052412-Case.1

- Rodrigues, D. R., Wilson, K. M., & Bielke, L. R. (2021). Proper immune response depends on early exposure to gut microbiota in broiler chicks. Frontiers in Physiology, 12, 758183. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.758183

- Rubio, L. A. (2019). Possibilities of early life programming in broiler chickens via intestinal microbiota modulation. Poultry Science, 98(2), 695-706. doi:10.3382/ps/pey416

- Rychlik, I. (2020). Composition and function of chicken gut microbiota. Animals, 10(1), 103. doi:10.3390/ani10010103

- Sandvang, D., Capern, L. C., Meuter, A., & Betz, S. (2024). Évaluation in vitro de la capacité d’inhibition d’un probiotique triple souche de bacillus sur des isolats cliniques d’Enterococcus cecorum [Communication]. 15e Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie Gras, Tours, 595-599.

- Sary, K., Brochu-Morin, M. E., & Boulianne, M. (2018). Enterococcus cecorum chez la volaille. Une maladie en émergence au Québec (Bulletin zoosanitaire). RAIZO. https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/agriculture-pecheries-alimentation/sante-animale/surveillance-controle/raizo/reseau-aviaire/Bulletinzoosanitaire_enterococcuscecorum_volaille_MAPAQ.pdf

- Schreier, J., Rautenschlein, S., & Jung, A. (2021). Different virulence levels of Enterococcus cecorum strains in experimentally infected meat-type chickens. PLoS ONE, 16(11), e0259904. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259904

- Schreier, J., Karasova, D., Crhanova, M., Rychlik, I., Rautenschlein, S., & Jung, A. (2022a). Influence of lincomycin-spectinomycin treatment on the outcome of Enterococcus cecorum infection and on the cecal microbiota in broilers. Gut Pathogens, 14(1), 3. doi:10.1186/s13099-021-00467-9

- Schreier, J., Rychlik, I., Karasova, D., Crhanova, M., Breves, G., Rautenschlein, S., & Jung, A. (2022b). Influence of heat stress on intestinal integrity and the cæcal microbiota during Enterococcus cecorum infection in broilers. Veterinary Research, 53(1), 110. doi:10.1186/s13567-022-01132-y

- Schwartzman, J. A., Lebreton, F., Salamzade, R., Shea, T., Martin, M. J., Schaufler, K., Urhan, A., Abeel, T., Camargo, I. L. B. C., Sgardioli, B. F., Prichula, J., Frazzon, A. P. G., Giribet, G., Tyne, D. V., Treinish, G., Innis, C. J., Wagenaar, J. A., Whipple, R. M., Manson, A. L., … Gilmore, M. S. (2024). Global diversity of enterococci and description of 18 previously unknown species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(10), e2310852121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2310852121

- Scupham, A. J., Patton, T. G., Bent, E., & Bayles, D. O. (2008). Comparison of the cecal microbiota of domestic and wild turkeys. Microbial Ecology, 56(2), 322-331. doi:10.1007/s00248-007-9349-4

- Sharma, P., Gupta, S. K., Barrett, J. B., Hiott, L. M., Woodley, T. A., Kariyawasam, S., Frye, J. G., & Jackson, C. R. (2020). Comparison of antimicrobial resistance and pan-genome of clinical and non-clinical Enterococcus cecorum from poultry using whole-genome sequencing. Foods, 9(6), 686. doi:10.3390/foods9060686

- Shterzer, N., Rothschild, N., Sbehat, Y., Dayan, J., Eytan, D., Uni, Z., & Mills, E. (2023). Vertical transmission of gut bacteria in commercial chickens is limited. Animal Microbiome, 5(1), 50. doi:10.1186/s42523-023-00272-6

- Silberborth, A., Schnug, J., Rautenschlein, S., & Jung, A. (2024). Serological monitoring of Enterococcus cecorum specific antibodies in chickens. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, 269, 110714. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2023.110714

- Souillard, R., Laurentie, J., Kempf, I., Le Caër, V., Le Bouquin, S., Serror, P., & Allain, V. (2022). Increasing incidence of Enterococcus-associated diseases in poultry in France over the past 15 years. Veterinary Microbiology, 269, 109426. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2022.109426

- Souillard, R., Laurentie, J., Repoila, F., Kempf, I., & Serror, P. (2024). Enterococcus cecorum, un agent pathogène opportuniste des volailles : mieux le connaitre pour une meilleure maitrise en élevage [Communication]. 15e Journées de la Recherche Avicole et Palmipèdes à Foie Gras, Tours. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-04547075v1

- Stalker, M. J., Brash, M. L., Weisz, A., Ouckama, R. M., & Slavic, D. (2010). Arthritis and osteomyelitis associated with Enterococcus cecorum infection in broiler and broiler breeder chickens in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 22(4), 643-645. doi:10.1177/104063871002200426

- Suyemoto, M. M., Barnes, H. J., & Borst, L. B. (2017). Culture methods impact recovery of antibiotic-resistant Enterococci including Enterococcus cecorum from pre- and postharvest chicken. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 64(3), 210-216. doi:10.1111/lam.12705

- Szeleszczuk, P., Dolka, B., Zbikowski, A., Dolka, I., & Peryga, M. (2013). First case of enterococcal spondylitis in broiler chickens in Poland. Medycyna Weterynaryjna, 69(5), 298-303. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84877952513&partnerID=40&md5=58c76d2664df507d9d3b7c1b11fb18f5

- Tessin, J., Jung, A., Silberborth, A., Rohn, K., Schulz, J., Visscher, C., & Kemper, N. (2024). Detection of Enterococcus cecorum to identify persistently contaminated locations using faecal and environmental samples in broiler houses of clinically healthy flocks. Avian Pathology, 53(4), 312-320. doi:10.1080/03079457.2024.2334682

- Thofner, I., & Christensen, J. P. (2016). Investigation of the pathogenesis of Enterococcus cecorum after intravenous, intratracheal or oral experimental infections of broilers and broiler breeders [Conférence]. VETPATH, Prato (Italy).

- Wideman, R. F. (2016). Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis and lameness in broilers: A review. Poultry Science, 95(2), 325-344. doi:10.3382/ps/pev320

- Wijesurendra, D. S., Chamings, A. N., Bushell, R. N., Rourke, D. O., Stevenson, M., Marenda, M. S., Noormohammadi, A. H., & Stent, A. (2017). Pathological and microbiological investigations into cases of bacterial chondronecrosis and osteomyelitis in broiler poultry. Avian Pathology, 46(6), 683-694. doi:10.1080/03079457.2017.1349872

- Wood, A. M., MacKenzie, G., McGillveray, N. C., Brown, L., Devriese, L. A., & Baele, M. (2002). Isolation of Enterococcus cecorum from bone lesions in broiler chickens [2]. Veterinary Record, 150(1), 27. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0037021879&partnerID=40&md5=f90786da573d92519c7acc5bf77457af

- Zhou, B. H., Jia, L. S., Wei, S. S., Ding, H. Y., Yang, J. Y., & Wang, H. W. (2020). Effects of Eimeria tenella infection on the barrier damage and microbiota diversity of chicken cecum. Poultry Science, 99(3), 1297-1305. doi:10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.073

- Zuidhof, M. J., Schneider, B. L., Carney, V. L., Korver, D. R., & Robinson, F. E. (2014). Growth, efficiency, and yield of commercial broilers from 1957, 1978, and 2005. Poultry Science, 93(12), 2970-2982. doi:10.3382/ps.2014-04291

Abstract

In less than 20 years, Enterococcus cecorum has become one of the major pathogens in broiler farms, distributed worldwide. This opportunistic bacterium is a commensal of the poultry gut, responsible for locomotor disorders that can lead to flock mortality. E. cecorum is a cause of poor animal welfare, increased use of antibiotics and economic losses. This review aims to establish a link between E. cecorum infections and the current physiological and molecular knowledge of the bacterium. Genomic analyses indicate that clinical isolates of E. cecorum are adapted to intestinal colonisation of chicks from the very first days of life. Conversely, commensal strains colonise the intestine later, at the earliest during the third week of life. The contamination routes of farms and the factors that could favour E. cecorum infection are most likely multiple: vertical and horizontal transmissions, zootechnical parameters, biosecurity practices and animal susceptibility. This review also presents a number of ideas under development to improve the control of E. cecorum on farms and prevent infections.

Attachments

No supporting information for this article##plugins.generic.statArticle.title##

Views: 3595

Views: 3595

Downloads

PDF: 333

PDF: 333

XML: 26

XML: 26