Social behaviour of the domestic pig and its importance for animal welfare on farms (Full text available in English)

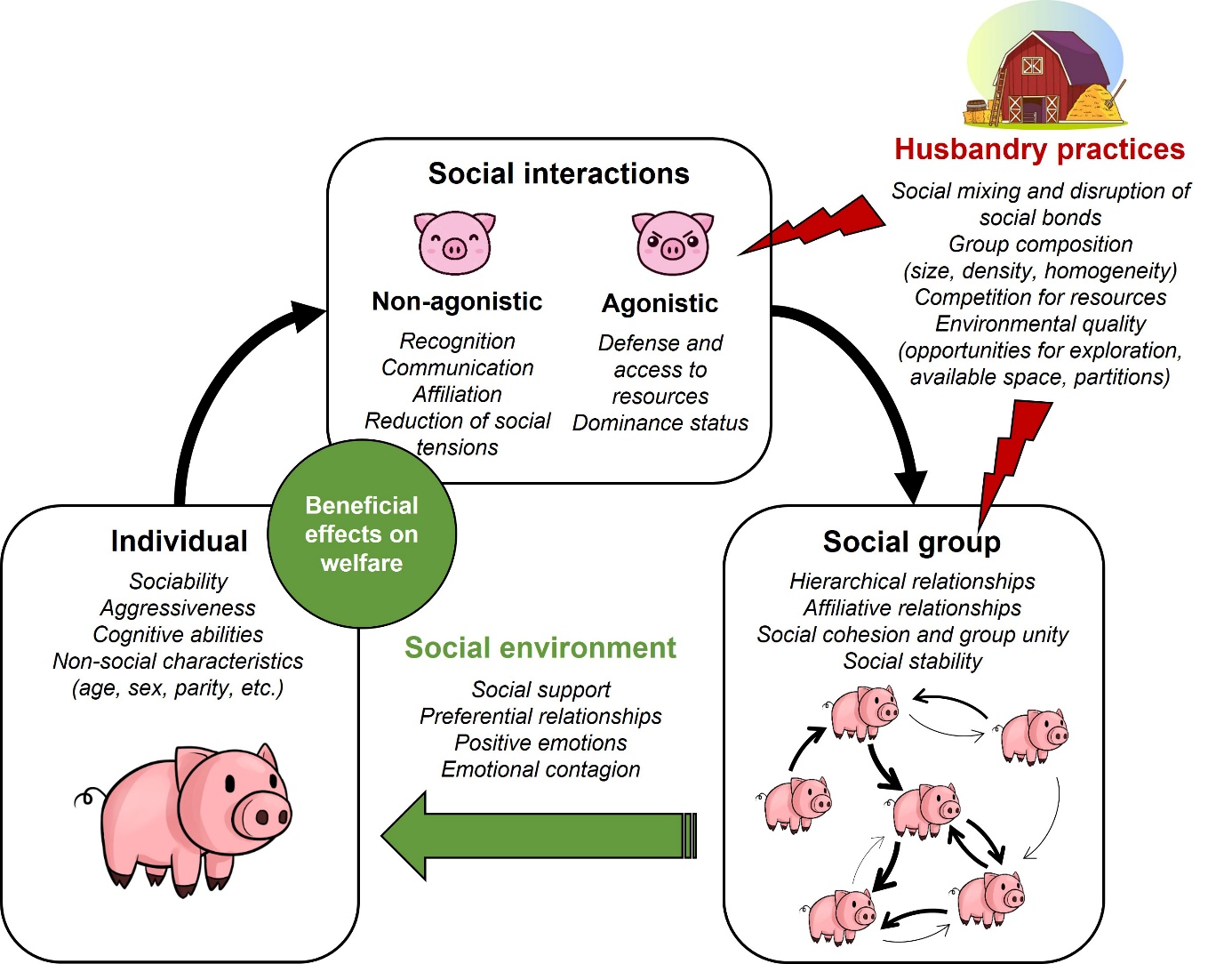

The pig is a social species that lives in groups whose structure is regulated by a wide range of agonistic and non-agonistic interactions. The ability of pigs to express a full social repertoire and to live in stable groups is vital to their welfare on the farm. This must be taken into account when managing groups of animals and designing farming systems.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, maintaining animal welfare in livestock farming has become a major social concern in Europe. Although the concept of animal welfare has been redefined many times over the past century, the ability of domestic animals to express behaviours typical of their species emerged as early as the 1960s as a key criterion for animal welfare (Thorpe, 1969). In 1993, the Farm Animal Welfare Council defined animal welfare as a state respecting five major freedoms: i) freedom from hunger, thirst, or malnutrition; ii) freedom from physical discomfort; iii) freedom from pain, injury, or disease; iv) freedom from fear and distress; and v) the ability to express behaviours typical of the species (Farm Animal Welfare Council, 1993). In 2018, the Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l'alimentation, de l'environnement et du travail (ANSES) proposed redefining animal welfare as "the positive mental and physical state linked to the satisfaction of its physiological and behavioural needs, as well as its expectations. This state varies according to the animal's perception of the situation" (ANSES, 2018). While the importance of expressing species-typical behaviours is also included in this definition, it further proposes assessing welfare from the animal’s point of view, taking into account its mental perception of its environment, which varies according to its experience, sensory and cognitive abilities, and expectations. Moreover, the concept of a positive mental state implies not only limiting unpleasant experiences likely to generate negative emotions (such as pain, fear, or anxiety), but also offering animals opportunities to experience positive emotions, such as pleasure and satisfaction.

Like most farm animals, pigs are a social species that live in groups whose structure and organisation are maintained through a range of agonistic (e.g. aggression, avoidance) and non-agonistic (e.g. snout contacts, nosing; Rault, 2012) interactions. The ability of animals to express the full range of their social behaviours and to live in stable groups is thus likely to be crucial for maintaining pig welfare by promoting the development of positive mental states. This should be taken into account in group management practices and system design. On intensive pig farms, the expression of social behaviours and the stability of group structure can be seriously disrupted by various practices, such as frequent regrouping, and by unsuitable management methods, including the formation of large groups characterised by high density and uniformity in weight or age.

In-depth knowledge of the social structure within groups of farmed pigs, as well as the social behaviours expressed by pigs at different life stages, is essential for understanding their role in maintaining animal welfare and for the effective management of farm animal groups (Gonyou, 2001). Nevertheless, until the early 2000s, research on farm animal welfare primarily focused on reducing animal discomfort, and studies on social behaviour focused almost exclusively on agonistic behaviours, such as fighting and aggression. In contrast, relatively few studies addressed non-agonistic behaviours, such as social nosing. Thus, the biological functions of these non-agonistic behaviours, and their potential importance for group cohesion and individual welfare, remain largely unexplored.

In this review, after briefly presenting the social characteristics of pig groups in free-range conditions, I will describe the full range of agonistic and non-agonistic behaviours observed in domestic pigs, based on available studies conducted in (semi-)free-range or intensive rearing systems. I will then examine how rearing conditions and management practices influence the expression of social behaviours in pigs. Finally, I will conclude by discussing the significance of non-agonistic behaviours for maintaining welfare in pig farming, and highlight directions for future research in this area.

1. Organisation and structure of pig social groups

1.1 Social organisation of pig groups

In free-ranging or semi-free-ranging conditions, domestic pigs adopt the same social organisation as wild boar or feral pigs (Podgórski et al., 2014), living in relatively stable matriarchal groups composed of one to four females and their offspring, which include one or more of the most recent litters (Gonyou, 2001; Graves, 1984). Pigs are a nidicolous species. Between 48 and 24 hours before farrowing, the sow separates from the group to search for a suitable site to build a nest for her piglets. The sow and her litter typically remain isolated from the group during the first week after farrowing (Jensen, 1986). From the second week of life, piglets begin to explore outside the nest with their mother (Jensen, 1988), gradually venturing farther from the nest in the following weeks to interact with other sows and piglets in the group. This is accompanied by a gradual decrease in suckling frequency and an increase in social contacts with piglets from other litters (Petersen et al., 1989). Weaning, defined as the transition from milk to solid feed, is a gradual process that occurs over several weeks. Piglets are typically fully weaned between 13 and 19 weeks of age, although a wide range (from 9 to 22 weeks) has been reported depending on conditions and methods (Newberry & Wood-Gush, 1985; Jensen & Recén, 1989; Stolba & Wood-Gush, 1989; Jensen & Stangel, 1992). Juvenile males leave the group at around seven to eight months to form small groups of two or three individuals. These male groups then gradually dissolve as they mature, with fully adult males becoming solitary males by around three years of age. Adult males join groups of sows episodically during periods of female sexual receptivity (Graves, 1984; Gonyou, 2001).

1.2 Social hierarchy within groups of pigs

Two main types of social structure have been described and studied in pigs: the suckling order among unweaned piglets, and the dominance hierarchy that develops thereafter. However, no link has been demonstrated between these two hierarchical orders (Ewbank, 1976).

From the first days of life, newborn piglets establish a feeding order by fighting for access to the teats. Larger piglets tend to secure and defend the the most anterior and posterior teats during suckling, leaving the central teats to the smaller piglets (Ewbank, 1976). This preference for the more extreme teats may be due to the anterior teats being larger and more widely spaced, and thus more accessible,and the anterior and posterior teats producing more milk than the central ones. However, this may alsobe a direct consequence of greater stimulation by larger, more vigorous piglets (Ewbank, 1976). The suckling order typically stabilises within the first week of life.

In addition to the suckling order observed in unweaned piglets, pig groups are structured according to a quasi-linear dominance hierarchy, i.e. one involving only a few triangular relationships, which is established early on and is based on dominance-subordination relationships (Meese & Ewbank, 1973; Puppe et al., 2008). These dominance-subordination relationships are formed through repeated agonistic interactions between pairs of individuals, involving physical aggression, threats, and avoidance (Meese & Ewbank, 1973), and are characterised by a consistent outcome in favour of one member of the pair. The animal that regularly wins these interactions assumes the dominant status, while the animal that consistently loses becomes subordinate. Under optimal free-range or semi-free-range conditions, once the hierarchical order is established, generally within 24 to 48 hours after a social disturbance (e.g.,the departure of a dominant animal or the arrival of new individuals in the group), it is typically maintained without further need for physical aggression. Subordinate animals tend to systematically avoid confrontations with dominants, thereby preventing escalation of attacks. Hierarchical rank does not appear to depend on sex or body weight, and this hierarchical structure can be observed in both female groups and groups of young males (Meese & Ewbank, 1973).

2. Agonistic social interactions

2.1. Description

Agonistic behaviours include both aggressive behaviours and avoidance or flight responses to aggression (Meese & Ewbank, 1973). Contact aggressive behaviours include biting, head-knocks and shoulder-knocks (Jensen, 1980; Samarakone & Gonyou, 2009). In mutual fights, which are bilateral aggression between two individuals, the animals stand side by side (parallel position) or face to face (antiparallel position) and push each other violently with shoulder- and head-knocks, while biting or attempting to bite each other's neck, head or flanks (Figure 1a). Non-contact aggressive behaviours include attempted bites and threats, where an animal initiates a quick movement of the head or front of the body towards another animal, with its mouth open or closed, as well as chases, in which one animal pursues another fleeing individual (Rault, 2016a).

Figure 1: Different social interactions in pigs.

2.2. Main functions

As mentioned above, aggression with contact, especially bilateral aggression, occurs mainly during events that disrupt social stability, for example when one or more individuals join the group (Ewbank, 1976). In these situations, unfamiliar pigs engage in intense mutual fighting to establish their hierarchical positions (Puppe et al., 2008; Peden et al., 2018). The resolution of fights is usually rapid, with a new hierarchical order established within 24 to 48 hours of the initial confrontation (Meese & Ewbank, 1973; Ewbank, 1976). Although these intense mutual fights involve significant energy expenditure, stress, and risk of injury, they are necessary. By enabling the initial formation of the hierarchy, these fights promote social stability, which in turn reduces the frequency of future aggressive interactions within the group (Puppe et al., 2008). Once the hierarchy is established, each individual knows its position relative to the others through inter-individual recognition, and the order is typically maintained by avoidance behaviours from subordinates rather than further fighting (Jensen, 1980). As a result, aggression becomes relatively rare or even absent within stable groups (Stolba & Wood-Gush, 1989). Nevertheless, occasional aggression may still occur, particularly when dominant individuals defend valuable resources such as food (Graves, 1984), or when a sow is defendingher nest after farrowing.

3. Non-agonistic social interactions

3.1. Description

Pigs engage in numerous non-agonistic interactions, often referred to as sociopositive interactions, although their truly “positive” nature has yet to be confirmed. The non-agonistic interaction that has received the most attention is social nosing, which involves an animal smelling or touching a part of a conspecific's body with its snout, thus requiring close proximity between the individuals involved. Several types of social nosing have been described in pigs, such as snout-to-snout contacts (Figure 1b) and nosing of other body parts or the head (Figures 1c and 1d; Jensen, 1980; Camerlink & Turner, 2013; Camerlink et al., 2021; Clouard et al., 2022, 2023). These social contacts are often brief, lasting about a second, and may occur within sequences of longer-lasting behaviours, such as during social play or while walking, sometimes making them difficult to measure reliably.

Pigs are also thought to engage in allogrooming, as do other wild ungulates such as antelopes and deer (Spruijt et al., 1992), as well as domestic animals like horses and cattle (Val-Laillet et al., 2009). Grooming involves rubbing the snout against the body of another animal, and systematically licking or gently nibbling the skin or hair with the lips or teeth (Spruijt et al., 1992; Camerlink et al., 2021; Clouard et al., 2024b). Pigs generally perform this behaviour in sequences lasting several tens of seconds. While allogrooming has been observed in pigs under semi-free-range conditions and in intensive rearing systems (Stolba & Wood-Gush, 1989; Camerlink & Turner, 2013; Camerlink et al., 2021, 2022; Clouard et al, 2024b), its existence remains debated (Špinka, 2009). For a long time, allogrooming was not differentiated from social nosing in ethograms of pig social behaviour (Camerlink & Turner, 2013; Clouard et al., 2022). In recent years, however, ethologists have reconsidered the value of identifying allogrooming as a distinct behaviour (Camerlink et al., 2021, 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b). Indeed, studies have shown that the prevalence of allogrooming is much lower than that of social nosing in pigs (Camerlink et al., 2021, 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b), suggesting that these two behaviours are mechanistically and functionally distinct.

Whether in stable social situations or following regrouping, in semi-free or intensive rearing conditions, and regardless the age of the individuals, non-agonistic interactions are naturally more frequent than agonistic interactions (Stolba & Wood-Gush, 1989; Camerlink et al., 2021; Clouard et al., 2022). In fact, non-agonistic interactions occur very often, with snout-to-body and snout--to-snout contacts accounting for up to 78% of all social interactions observed in piglets (Clouard et al., 2022, 2023), although prevalence rates vary between studies depending on which social behaviours are considered and the observation methods used (Camerlink et al., 2021). This high prevalence of non-agonistic interactions suggests that these behaviours hold major biological significance for pigs.

3.2 Presumed main functions

Based on current knowledge, the precise functions of non-agonistic contacts have not been clearly established. However, several convincing hypotheses suggest these behaviours play roles in individual recognition and social communication, the formation of affiliative relationships, stress reduction, and fulfilling an intrinsic need for exploration (Camerlink & Turner, 2013).

a. Individual recognition and social communication

Inter-individual recognition is an essential cognitive capacity for maintaining stable social structures and organisation. Snout contacts likely play a key role in conspecific recognition, as well as in social communication, by enabling the detection, recognition, and processing of numerous olfactory signals (Clouard & Bolhuis, 2017). Pigs can recognise conspecifics based solely on olfactory information (Kristensen et al., 2001). Oxytocin, a hormone known to enhance olfactory memory and social recognition (Ferguson et al., 2001), appears to influence these behaviours. Camerlink et al (2016) showed that, following separation, the frequency of snout-to-snout interactions upon reunion, but not snout-to-body interactions, was reduced in pigs administered oxytocin. This suggests that oxytocin-treated pigs are better able to recognise their conspecifics, and thus need fewer snout-to-snout contacts to gather social olfactory cues. These results indicate that snout-to-snout contacts play a crucial role in social recognition through the collection of olfactory information (Camerlink & Turner, 2013; Clouard et al., 2024b). In line with this theory, we observed that mixing litters of piglets at weaning, a common farm practice, increased the frequency of snout-to-snout contacts between piglets on the day of weaning by threefold compared to the following day, while the frequency of snout-to-body contacts remained unchanged. This result may further confirm the role of snout-to-snout contacts in social recognition (unpublished results).

In addition to communication between juveniles and adults, snout-to-snout contacts are believed to play an important role in mother-to-juvenile communication. Unlike other farm animals such as cattle or sheep, sows do not groom or lick their piglets (Whatson & Bertram, 1983). Thus, whether in free-range or intensive rearing conditions, sows primarily communicate with their piglets through vocalisations, nosing and snout contacts (Whatson & Bertram, 1983; Jensen, 1986, 1988; Gonyou, 2001). Piglets also frequently initiate snout-to-snout contacts with their mothers, especially during suckling episodes, both before the onset of pre-nursing massage and even more often in the minutes following milk ejection (Whatson & Bertram, 1983; Jensen, 1988; Jensen et al., 1991). These contacts before suckling may facilitate the recognition of piglets by their mother, which can be particularly beneficial by preventing the mother from suckling piglets from other litters (Whatson & Bertram, 1983). Beside its role in social recognition, snout-to-snout contacts may also be involved in social communication related to nutritional needs. While the frequency of young-to-mother contact before suckling remains stable during lactation, contacts following milk ejection tend to increase over time (Jensen et al., 1991). Moreover, snout-to-snout contacts are less frequent during non-nutritive suckling (i.e. without milk ejection) than during nutritive suckling (Whatson & Bertram, 1983), suggesting a direct link between these contacts and milk acquisition during suckling. Despite these insights, the full functions of these contacts, observed in both captive and wild domestic pigs, have yet to be fully elucidated.

b. Affiliative relationships

Group structure is characterised by components beyond dominance, such as affiliation and leadership (cf. Ewbank, 1976; Khatiwada et al., 2024), which have received little or no study in pigs. Affiliative relationships are considered a fundamental component of social structures due to their role in maintaining social cohesion. Non-reproductive affiliative relationships, sometimes referred to as “friendships”, are defined as patterns of spatial interactions or associations where individuals perform more bidirectional affiliative interactions with each other, such as grooming, or spend more time in close proximity during synchronous activities like resting or grazing, compared to other group members (Brent et al., 2014). Similar to cattle (Reinhardt & Reinhardt, 1981) or their wild relatives (Podgórski et al., 2014), pigs also display preferential affiliative relationships. Observational studies in semi-free-range conditions have shown that piglets exhibit short-term social preferences for littermates based on resting proximities, behavioural synchronisation, and non-agonistic interactions, such as social nosing or play (Newberry & Wood-Gush, 1986; Petersen et al., 1989; Jensen & Stangel, 1992). More recently, studies conducted under controlled experimental conditions and/or using social network analysis methods (box 1) appear to confirm the existence of preferential social relationships within groups of pigs for body nosing (Goumon et al., 2020) and allogrooming (Figure 2; Clouard et al., 2024b). In contrast, snout-to-snout contacts were expressed randomly within groups (Goumon et al., 2020; Clouard et al., 2024b). Thus, allogrooming or body nosing may play important roles in the development and maintenance of affiliative relationships within pig groups (Camerlink & Turner, 2013; Goumon et al., 2020), whereas snout-to-snout contacts appear more involved in social communication (cf. previous section; Clouard et al., 2024b). Moreover, allogrooming was performed by fewer group members compared to snout-to-snout or snout-to-body interactions, suggesting that allogrooming help strengthen or maintain specific social bonds between particular individuals (Clouard et al., 2024b), rather than supporting social cohesion at the group level as proposed by other authors (Camerlink & Turner, 2013). Thus, certain non-agonistic interactions, such as allogrooming, could contribute to the development and maintenance of affiliative relationships in pigs. However, further research is needed to confirm these hypotheses and to better understand and characterise these affiliative relationships and their role in pig welfare on farms (see section 5.2).

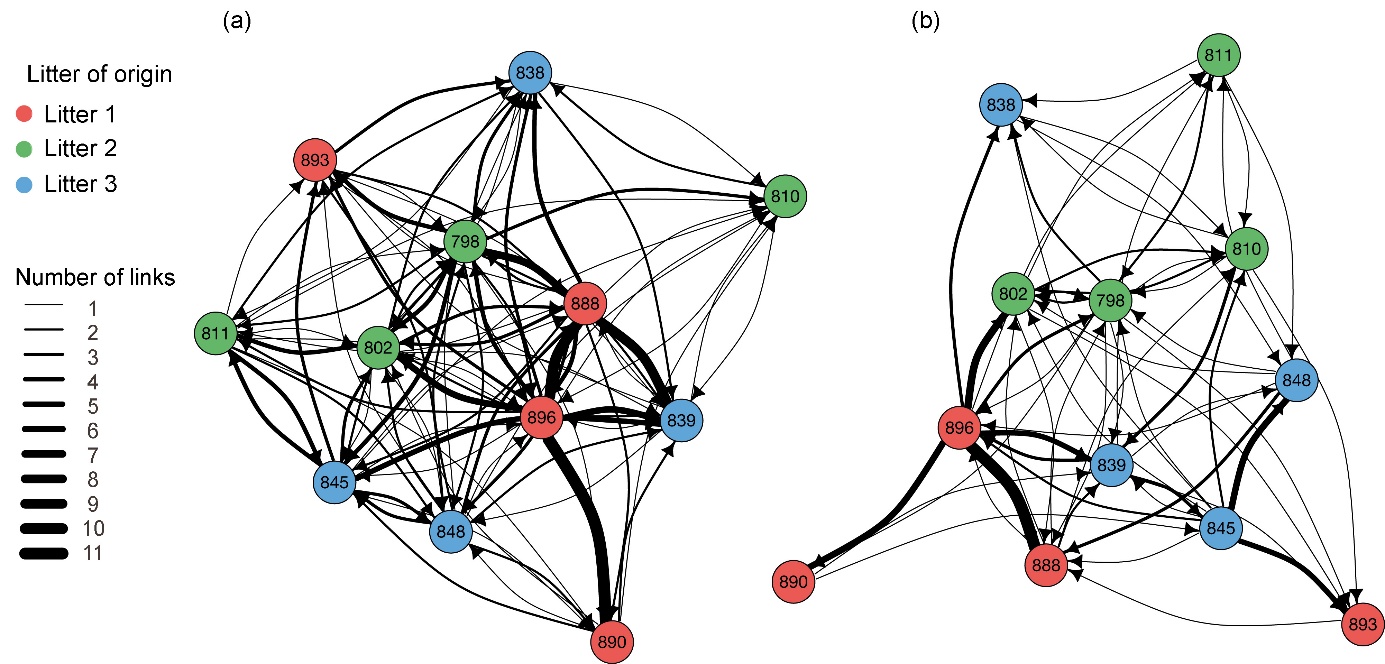

Figure 2: Social networks for allogrooming behaviour in a group of 12 pigs during the (a) post-weaning and (b) fattening phases (Clouard et al., 2024b).

Social network analysis is a powerful method for identifying and quantifying social relationships within groups of animals (Wasserman & Faust, 1994; Whitehead, 2008) and it has been widely applied across various disciplines, including economics, computer science, and sociology. With the rapid development of accessible software and the publication of articles and books highlighting the value of this approach for behavioural sciences, social network analysis has recently experienced a boom in the field of applied ethology (Makagon et al., 2012), and more specifically in research into the welfare of farm animals (Foris et al., 2021; Clouard et al., 2024b).

The analysis of social networks is based on the graphical representation of relationships between individuals, called nodes, and the interactions between them, called links (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). These graphical representations, or sociograms (Figure 2), allow visualisation of the presence or absence of interactions (e.g. aggression, grooming) between each group member. These sociograms can also provide more complex information. In weighed networks, the strength of interactions, calculated based on the frequency or duration of interactions between two individuals, is represented by the thickness of the links. In directed networks, the direction of interactions is indicated by arrows at the ends of links to identify the initiator and receiver. Finally, individual characteristics such as age, dominance rank, or gender can be incorporated into the sociogram by assigning different colours or sizes to the nodes (Makagon et al., 2012).

By analysing social networks, various social network metrics can be calculated at both group and individual levels, helping to quantify key social concepts.

At the group level, density, the proportion of existing links to possible links, provides information on the degree to which all the individuals in a group interact with each other. Reciprocity indicates the degree to which individuals share reciprocal interactions, while the clustering coefficient measures the probability that two nodes are connected, given that they are both connected to the same node. The tendency of nodes to form strongly interconnected groups provides insight into the strength and unity of the group. Finally, assortativity, calculated by an assortativity coefficient comparing the attributes of connected nodes, determines the extent to which individuals in the group preferentially connect with individuals sharing or not sharing common characteristics (e.g. sex, age, dominance status). Parameters measured at the group level thus provide an indication of the group's social cohesion, solidity, or level of unity (e.g. presence of interconnected or non-interconnected sub-groups). Applied to groups of pigs on farms, these metrics can be used, for example, to monitor changes in social structures following modifications to groups (removal or addition of individuals) or to assess the impact of certain rearing conditions (e.g. density, enrichment) on social structure. These parameters can also identify individual determinants of social preferences within the group, such as whether pigs associate or interact preferentially with animals of the same social rank or sex.

At the individual level, various centrality parameters provide information about an individual’s importance within the network. Degree, the number of direct links an individual shares with others in the group, indicates the social position of certain individuals (e.g. highly connected and central individuals). In directed networks, a distinction is made between incoming degree (number of interactions directed towards the individual) and outgoing degree (number of interactions initiated by the individual). Closeness, the minimum distance connecting an individual to all other group members, provides insight into an individual's propensity to communicate with the entire group without relying on many intermediaries. It differs from degree in thatwhile degree takes into account only direct relationships, closeness considers both direct and indirect relationships. Betweenness, the number of times an individual lies on the shortest path between other individuals, identifies individuals who link different sub-groups. Parameters measured at the individual level can thus be used to identify key animals that play important roles in maintaining social cohesion or in transmitting behaviour. In pigs, for example, they help identify the central animals that maintain group cohesion or those that propagate behaviours most rapidly and broadly within the group.

In conclusion, social network analysis offers a robust and standardised methodological framework for better understanding and characterising social interactions at the individual level and social dynamics at the group level in farmed pigs. By quantifying key social parameters, this approach could help create rearing conditions or practices that respect social affinities or limit the spread of undesirable behaviours, such as aggression or cannibalism, thereby promoting animal welfare.

c. Stress reduction

Non-agonistic interactions may also play a role in alleviating tension and reducing stress within pig groups. Research suggests that frequent non-agonistic tactile contacts may serve as an adaptive strategy for certain individuals to cope with stressful situations, particularly those common in intensive farming systems, such as regrouping, high stocking densities, or limited space (Temple et al., 2011). Supporting this hypothesis, pigs exposed to negative human contacts have been found to display more social interactions following such stressful events (Rault, 2016b). This rise in snout contacts after conflicts or negative experiences could help ease social tensions through a phenomenon known as social support (Boissy et al., 2007; Rault, 2012), whereby the presence of a conspecific has beneficial effects on an individual's ability to cope with a challenge. Additionally, it is possible that non-agonistic behaviours like allogrooming are linked to dominance relationships within the group (Rault, 2019), as has been observed in cattle (Mülleder et al., 2003; Val-Laillet et al., 2009). According to this postulate, subordinate animals might display more non-agonistic behaviours to reduce social tensions, gain access to resources, or mitigate aggression from dominant animals. However, the existence of such associations between non-agonistic behaviour and dominance, likely modulated by the broader social context (Rault, 2019), remains to be clearly demonstrated in pigs (Camerlink & Turner, 2013).

3.3. Other non-agonistic behaviours

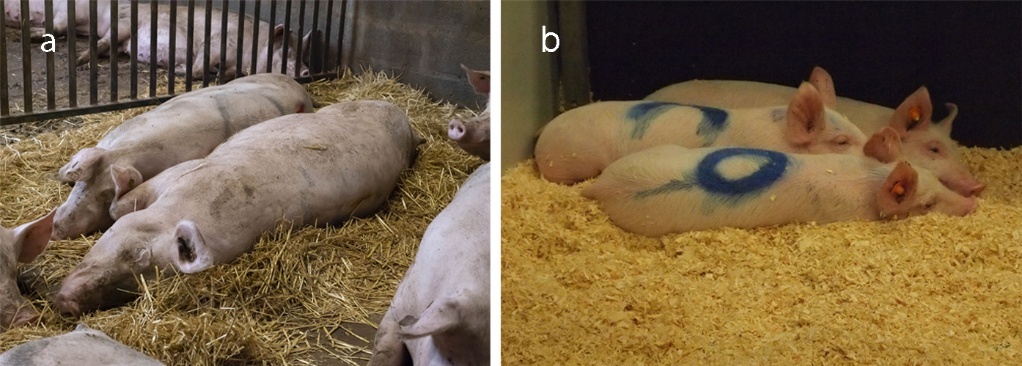

In addition to tactile snout contacts, pigs exhibit other social behaviours considered non-agonistic or sociopositive, such as maintaining close spatial proximity and synchronising activities like resting or exploring. Notably, pigs often rest or sleep in physical contact with conspecifics (Figure 3; Goumon et al., 2020; Camerlink et al., 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b). However, this behaviour does not appear to be random, and pigs show preferences in their choice of resting partners (Stookey & Gonyou, 1998; Durrell et al., 2004; Clouard et al., 2024b). Such preferences suggest that social proximity may contribute to the development or expression of social affinity, similarly to allogrooming or social nosing. Despite this, several studies have found no clear correlation between the expression of these non-agonistic interactions and spatial proximity (Goumon et al., 2020; Camerlink et al., 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b). This lack of correlation may indicate that these behaviours reflect distinct dimensions of sociality (Pearce et al., 2017; Camerlink et al., 2022). Another plausible explanation is that, in confined and socially dense environments, preferences identified based on spatial proximities may actually reflect a shared preference for specific areas of the living space, related to factors such as temperature, humidity or light (Camerlink & Turner, 2013; Goumon et al., 2020).

In juvenile pigs, social play complements snout contacts and spatial proximity as a key component of social behaviour. Juveniles engage in various types of play, including object play, locomotor play, and social play (Horback, 2014), with peak activity typically occurring between two and six weeks of age (Newberry et al., 1988; Clouard et al., 2022). Social play involves sequences of social interactions and locomotor behaviours performed simultaneously by two or more individuals, in a lively, uncoordinated manner. During these episodes, piglets may hop or pivot, toss their heads, run together around the pen, circle, or shove conspecifics, sometimes with biting attempts (Newberry et al., 1988). On common type of social play is play fighting, characterised by pushing and shoving, with or without biting, that mimics real fights but is generally less intense and involves less physical tension. These interactions are often preceded by distinctive "play signals", such as pivoting and tossing the head (Newberry et al., 1988), which help differentiate them from actual fights. Males tend to engage in more social play, particularly play fights, than females (Weller et al., 2019; Clouard et al., 2022). This sexual dimorphism in juvenile play is typically observed in species where adult social environment and roles differ significantly between males and females, as is the case in pigs (Weller et al., 2019). Social play is believed to contribute to the development of essential social skills, such as social recognition, as well as the physical and locomotor skills required for effective fighting later in life (Bekoff, 1984; Dobao et al., 1985; Kristensen et al., 2001). By promoting these social skills, social play facilitates its integration into the group and contributes to the maintenance of social cohesion within pig groups (Bekoff, 1984; Newberry et al., 1988).

4. Impact of rearing conditions on social behaviour

Pigs in commercial farming systems are typically reared under conditions that differ markedly from those encountered in semi-natural environments, particularly with regard to the size and composition of social groups, the physical environment, and social stability. These artificial rearing conditions can affect the ability of pigs to express the full range of their natural social behaviours, potentially leading to adverse effects on their welfare.

4.1. Social mixing: the special case of weaning

In pig farming, animals are subjected to successive regroupings throughout their lives. These regroupings, or social mixing, cause major upheavals in the balance of animal groups. Primiparous sows are often introduced into the group of pregnant females after insemination to renew the herd by 20-30% following the departure of culled sows. In the case of fattening pigs, regrouping is often carried out at the start of fattening to form batches of animals of the same sex or of similar weight, which facilitate herd management and allows for coordinated slaughter. Weaning is perhaps the most significant challenge for pigs on farms and has been the subject of extensive research. Under natural conditions, weaning is defined as the gradual transition from a mainly milky diet to an exclusively solid diet. In conventional farming, however, weaning is generally carried out particularly early and suddenly, and involves much more than a dietary change. Piglets are separated from their mothers overnight, usually between 21 and 28 days after birth. At the same time, they are typically re-housed in new pens and mixed with piglets from other litters. This social mixing leads to a temporary increase in fights which, although necessary for the establishment of a hierarchy, can be worsened by inadequate housing conditions (limited space, high stocking density, homogeneous groups), and result in injuries and sometimes significant lesions. The need to adapt simultaneously to nutritional, environmental, and social changes can cause considerable stress in some animals, particularly when these changes occur earlier than under “natural” conditions. This state of stress encourages the emergence of abnormal social behaviours, such as belly nosing or other oral manipulation of conspecifics (chewing and biting of the ears or tail; Metz & Gonyou, 1990). These behaviours can become a source of stress for other group members when repeated and prolonged on the same individuals. Moreover, a marked absence or significant reduction in play behaviour is often reported in the days or weeks following early weaning (Clouard et al., 2023). The increase in agonistic behaviours, at the expense of play and non-agonistic behaviours, is a strong indicator of the harmful impact of this practice on animal welfare.

Various genetic, nutritional, and group management strategies have been tested to limit aggression and stress during social mixing. Among these strategies, which are described in detail in the review by Peden et al. (2018), early socialisation has attracted particular interest. This strategy involves bringing together piglets from different litters during the lactation period (D'Eath, 2005; Salazar et al., 2018). Early socialisation thus mimics situations observed under natural conditions, allowing piglets to interact and gradually become familiar with piglets from other litters, thereby forming social relationships from the first weeks of life, particularly through play fights (D'Eath, 2005; Salazar et al., 2018). By promoting social learning and improving piglets' social skills (cf. section 3.3), these early play fights with piglets from other litters would enable animals to fight more efficiently (i.e. shorter fights with fewer injuries) and to establish the dominance hierarchy more quickly during subsequent social mixing, particularly at weaning (Salazar et al., 2018). This greater efficiency in establishing the hierarchy, combined with the formation of new groups composed of piglets already familiar with each other, would reduce the adverse effects associated with weaning by lowering aggression (in terms of duration or intensity), and thereby mitigating injuries and stress (e.g. lower peripheral cortisol levels). Early socialisation would thus appear to be a relevant strategy to improve piglet welfare without negatively affecting productive performance at weaning (D'Eath, 2005; Salazar et al., 2018).

Various practices, requiring more or less extensive facilities, can be implemented to achieve early socialisation. On some farms, this may simply involve opening the partitions between two adjacent farrowing pens or installing removable partitions and opening pen doors to give piglets access to the corridor (D'Eath, 2005; Salazar et al., 2018). Other systems, requiring a greater economic investment, have also been tested, such as group-housing systems that combine early socialisation, late weaning and enrichment of the physical and social environment (van Nieuwamerongen et al., 2015; Verdon et al., 2020). In addition to having positive effects on post-weaning weight gain, the social and physical enrichment provided by these systems appears to increase play behaviour and reduce oral manipulation and aggression after weaning compared to conventional individual farrowing systems. Beyond variability in system type, a wide range of age at the onset of socialisation has been reported, typically between 7 and 14 days, which may help explain differences in outcomes between studies (D'Eath, 2005; Salazar et al., 2018; Verdon et al., 2020). Moreover, the impact of these practices on the sow, including her welfare and productivity, remains insufficiently characterised. Some studies suggest that early socialisation may disrupt suckling episodes and promote cross-suckling (Verdon et al., 2020). Thus, although early socialisation is already practised on some farms, further studies are needed to dispel the doubts that still persist among some farmers, particularly regarding potential increases in workload or the risk of pathogen transmission (Peden et al., 2018).

4.2 Size, composition and density of social groups

Pigs are housed in groups formed by the farmer, which differ considerably from those observed in semi-natural conditions. Group composition, size and density are generally predetermined to maximise economic efficiency, optimise space use, and facilitate herd management (Estevez et al., 2007). These group management factors are believed to influence social behaviour, and may particularly promote excessive aggression, which can result in serious injuries and elevated stress levels (Estevez et al. 2007).

Firstly, pigs are often kept in homogeneous groups, composed exclusively of animals at the same physiological stage, and sometimes even of the same sex or weight (Estevez et al., 2007). However, such high levels of social homogeneity can hinder the establishment of a hierarchy in the absence of older or heavier individuals who would normally assert dominance more easily, potentially leading to excessive and prolonged aggression (Andersen et al., 2000). In fattening pigs, fights are shorter between individuals of different weights than between those of similar weight (Andersen et al., 2000). Among pregnant sows, hierarchical position is strongly correlated with parity and weight, but only in groups characterised by a high degree of heterogeneity in these traits (Lanthony et al., 2022), confirming that heterogeneity facilitates both the establishment and maintenance of hierarchy. Group size also appears to significantly influence social behaviour, particularly aggression. A decrease in aggression has been observed with increasing group size (Estevez et al., 2007; Samarakone & Gonyou, 2009). Among the various theories proposed to explain this phenomenon (Estevez et al. 2007), the 'non-aggression futures' theory suggests that hierarchy formation is beneficial mainly in small groups, as seen undernatural conditions. In larger groups, animals may adopt alternative strategies to maintain social stability and minimise aggression, such as forming sub-groups governed by “local” hierarchies. However, the impact of group heterogeneity or size on aggression seems to depend heavily on resource competition and stocking density. Aggression resulting from social mixing or suboptimal group management may be exacerbated by poor housing conditions, for example, when access to food, water, or resting areas is limited (Andersen et al., 2000; Estevez et al., 2007; Samarakone & Gonyou, 2009). These findings highlight the importance of limiting competition over resources and suggest that pigs adjust their social strategies to their social environment, illustrating the plasticity of their social behaviour, which cannot be reduced to simple dominance/subordination dynamics (Estevez et al., 2007; Samarakone & Gonyou, 2009).

4.3. Environmental quality

Certain infrastructure-related factors may also influence social behaviour in farmed pigs.

Providing sufficient available space is considered crucial for the proper expression of social behaviour. As mentioned earlier, pigs engage in intense fights during social mixing. However, limited space can physically hinder these fights and prevent subordinate animals from escaping. The inability to display submissive behaviours that would normally end the fight can result in prolonged fights without a clearly identified winner (Gonyou, 2001). In conventional farming, when increasing available space is not economically or technically feasible, an alternative strategy to reduce aggression may involve designing compartmentalised living areas. This can include adding opaque partitions to create separate areas within the pen, giving animals the opportunity to isolate themselves and avoid agonistic interactions. However, the beneficial effects of such strategies have yet to be confirmed (Bulens et al., 2017).

Research has also shown that the quality of the environment affects the expression of social behaviour. In particular, access to complex or enriched environments may reduce undesirable social behaviours. For example, pregnant sows reared in enriched conditions, with more available space and access to accumulated straw, showed less aggression than sows kept on slatted floors (Lopes et al., 2023). During the lactation period, piglets housed in free farrowing pens interacted more frequently with the sow, including snout contacts, played more, and showed less oral manipulation of conspecifics than piglets housed in farrowing crates (Singh et al., 2017). Similarly, piglets reared under enriched conditions at farrowing and/or weaning, with more available space and access to enrichment materials or straw, expressed fewer oral manipulations of conspecifics, such as belly nosing or biting of tail, ears, or other body parts, than animals reared in conventional barren environments (Beattie et al., 2000; Bolhuis et al., 2005; Oostindjer et al., 2011). Finally, piglets reared outdoors, either during the lactation period or after weaning, spent less time belly nosing, orally manipulating, or aggressing their conspecifics than piglets reared indoors (Hötzel et al., 2004).

The expression of non-agonistic behaviour also appears to be strongly influenced by environmental quality. For example, in enriched environments (with more available space and straw on the floor), suckling or weaned piglets engage in more locomotor social play (Bolhuis et al., 2005), but display similar (Bolhuis et al., 2005) or even reduced levels, of contacts with conspecifics (e.g. nosing, massaging, gentle nibbling of conspecifics; Beattie et al., 2000) compared to piglets reared in barren conditions. Similarly, in fattening Iberian pigs, the prevalence of positive social behaviours, such as nosing and grooming, was much lower (2.3%) in extensive systems characterised by low density and prolonged outdoor access than in intensive conditions (Temple et al., 2011). In pregnant sows, access to a more spacious environment and straw bedding is also associated with a reduced frequency of social nosing (Lopes et al., 2023). This reduction in the expression of social nosing in enriched environments may suggest that these conspecific-oriented exploratory behaviours partly reflect the pig's strong intrinsic motivation to explore. In conditions where substrates for exploration are not provided, as is often the case in intensive indoor housing, animals may redirect their exploratory drive towards conspecifics (Camerlink et al., 2016; Clouard et al., 2024b). In line with this postulate, strong correlations have been found between environmental exploration and social nosing (such as snout-to-snout and snout-to-body contacts), even when exploratory substrates are present (Camerlink & Turner, 2013).

Environmental factors such as air quality and light levels in housing facilities also influence social behaviour. For instance, weaned pigs kept in rooms with high atmospheric ammonia levels spent less time feeding in contact with others than in low-ammonia rooms, suggesting reduced social synchronisation and tolerance (O'Connor et al., 2010). In such conditions, the pigs also played less and were more aggressive (O'Connor et al., 2010; Parker et al., 2010). Moreover, the negative effect of high ammonia on aggressions was exacerbated under low light levels (Parker et al., 2010). These disturbances in social behaviour are thought to result from the negative effects of poor environmental conditions, such as polluted air and low light levels, on pigs' ability to perceive the olfactory and visual signals essential for communication and social recognition (O'Connor et al., 2010; Parker et al., 2010). In confined housing, the accumulation of airborne contaminants and dust may mask olfactory cues (Jones et al., 2001) and contribute to inflammation of the vomeronasal organ (Hellekant & Danilova, 1999), thereby compromising nasal mucosa integrity and receptor functionality. In line with this hypothesis, studies have found a positive association between inflammation of the vomeronasal organ and the severity and number of skin lesions, indicating more frequent or intense fights due to impaired hierarchy formation (Hellekant & Danilova, 1999). Additionally, chronic exposure to high ammonia levels was shown to alter pigs’ preferences for familiar versus unfamiliar individuals. This shift in social preference may stem from impaired social recognition mechanisms (Kristensen et al., 2001) or from a deterioration in emotional state (e.g. pain or discomfort), which can disrupt social behaviour. Overall, these studies highlight the critical role of air quality in shaping social communication and recognition in pigs.

5. Research perspectives on social behaviour to improve animal welfare

Since the beginning of research into animal welfare in livestock farming, work has mainly focused on reducing poor welfare in farm animals by identifying situations or practices likely to generate negative emotional states. The impact of farming conditions and practices (e.g. social mixing, group characteristics, housing conditions) on the expression of agonistic behaviours, such as aggression or oral manipulation of conspecifics (e.g. tail or ear biting), has been particularly well characterised, while non-agonistic behaviours have so far received more limited attention. However, the last two decades have seen a major shift in both societal and scientific perceptions of animal welfare. It is now recognised that limiting animals’ negative experiences and suffering is not sufficient to guarantee their welfare. The emerging concept of “positive welfare” postulates animal welfare can only be ensured by providing animals with the opportunity to have positive and rewarding experiences, enabling them to feel positive emotions (Rault et al., 2023, 2025). For social species, these positive experiences are likely to include the opportunity to live in stable groups, to develop and maintain social bonds, and to express positive social interactions. These elements are thus essential for promoting animal welfare in livestock farming (Boissy et al., 2007). In this context, major advances have been made regarding non-agonistic behaviour in pigs and the influence of rearing conditions on its expression (see section 4).

5.1. Towards a better understanding of the functions of non-agonistic behaviours

Despite these advances, more needs to be done to fully understand the function of non-agonistic behaviour and its importance in maintaining welfare on farms. Several areas of research deserve particular attention.

It is crucial to better characterise the contexts in which each type of non-agonistic behaviour is expressed, in order to better understand their functions. This can be achieved by studying their specific manifestations across various rearing systems, such as conventional intensive systems, enriched intensive systems, or extensive systems. For example, a high frequency of social nosing in barren environments compared with enriched environments or those providing outdoor access would suggest that the expression of these behaviours is strongly influenced by pigs' intrinsic motivation to explore, even in the absence of suitable substrates. Conversely, a high frequency of allogrooming behaviours or close spatial proximity in extensive systems could highlight their role in maintaining social bonds and cohesion. Similarly, analysing the expression of different types of non-agonistic behaviours following events that disrupt the social group (e.g. social mixing, increased competition for certain resources) would help clarify their function. Furthermore, a better understanding of the simultaneous evolution of agonistic and non-agonistic behaviours in situations that generate competition or frustration could shed light on their role. For instance, in a stable social group, an increase in snout contacts during a competitive situation (e.g. reduced number of troughs) accompanied by a decrease in agonistic interactions, could support the idea that such contacts help reduce social tension within the group, as suggested in cattle (Val-Laillet et al., 2009) or pigs (Camerlink & Turner, 2013).

In conclusion, improving our understanding of non-agonistic behaviours, their functions, and the contexts in which they are expressed is a key step toward improving the welfare of pigs in farming systems. This research will help better integrate the concept of positive welfare into livestock management practices.

5.2 The importance of maintaining affiliative relationships for welfare

In addition to advancing our understanding of non-agonistic behaviour and the impact of husbandry practices on its expression, it is essential to confirm the existence of affiliative relationships in pigs, and to explore their role, dynamics over time, and potential contribution to animal welfare.

As described in section 3.2, pigs, like ruminants (e.g. Foris et al., 2021), appear to express more or less durable social preferences through certain non-agonistic behaviours (Durrell et al., 2004; Goumon et al., 2020; Camerlink et al., 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b). However, most studies have identified these preferences solely based on spatial proximity during exploration (Goumon et al., 2020) or rest (Stookey & Gonyou, 1998; Durrell et al., 2004; Goumon et al., 2020; Camerlink et al., 2022). Yet, in pigs, social preferences based on spatial proximity are not correlated with those observed social contacts, such as grooming or snout-to-snout contacts (Camerlink et al., 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b), suggesting that spatial proximity may be influenced by non-social factors. For instance, in indoor rearing systems, close proximity may reflect shared preferences for areas offering better thermal comfort or a more favourable environment, rather than genuine social affiliation. Moreover, these social preferences do not always appear to be robust or stable over time and across contexts. They often do not persist after a change of pen (Durrell et al., 2004), although recent studies have reported exceptions (Clouard et al., 2024b). Preference may also vary depending on the activities being performed (Goumon et al., 2020) and evolve with age (Camerlink et al., 2022). Long-term studies that assess both spatial proximity and social contacts in non-confined environments are thus needed to better characterise the stability and durability of social relationships in pigs. Finally, affiliative relationships have been studied primarily in weaned and growing pigs (Durrell et al., 2004; Goumon et al., 2020; Camerlink et al., 2022; Clouard et al., 2024b). It would thus be relevant to investigate whether such relationships also exist at other physiological stages, such as in pregnant sows, which typically remain in the same social group over several successive pregnancies (Clouard et al., 2024a).

As well as confirming the existence of social affiliative relationships, it is important to identify the individual factors underlying their establishment, maintenance, and evolution. Observational studies of semi-free-ranging populations have shown that animals reared together from an early age express more affiliative behaviour toward each other than toward other individuals (Newberry & Wood-Gush, 1986), suggesting a strong influence of familiarity or kinship. More recently, studies using social network analysis have expanded our understanding though results have sometimes been contradictory. For instance, while several studies found no effect of familiarity, kinship, or sex on social preferences during resting (Durrell et al., 2004; Goumon et al., 2020), we have recently shown that weaned or fattening piglets tend to lie preferentially next to individuals from the same litter or of the same sex (Clouard et al., 2024b). Finally, growing pigs have been shown to prefer nosing (Goumon et al., 2020) or grooming (Clouard et al., 2024b) individuals of a different dominance rank.

This knowledge could make it possible to reconsider certain husbandry practices to better account for affiliative relationships in livestock and promote animal welfare. Keeping preferred partners together, by limiting social mixing, could, for example, reduce aggression and stress in farming environments. One promising strategy would be to littermates together throughout their lives, from birth through post-weaning to fattening. Considering these affiliative relationships could also enhance the effects of social support on stress. Social support refers to the phenomenon whereby the mere presence of one or more companions can alleviate the negative effects of stressful events on a target individual (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Rault, 2012). However, the presence of a random conspecific is not always sufficient to reduce the stress, and social support appears to be more effective between familiar individuals (Kanitz et al., 2014) or those with strong social bonds (Boissy & Le Neindre, 1990). Thus, maintaining pairs or groups of animals with preferential relationships could help reduce stress during aversive procedures, such as transport or handling on the farm (e.g. weighing, vaccination; Gonyou, 2001; Rault, 2012).

In conclusion, further research is needed to understand the impact of breaking affiliative bonds on the emotional state of farm animals and, conversely, to assess the benefits of preserving these preferential bonds in reducing stress and improving welfare, especially during stressful practices. This work will help to optimise husbandry practices by reinforcing the role of social support in promoting animal welfare.

5.3. Characterising individual variability in social behaviour

Like many behaviours, the social behaviour of farm animals exhibits considerable inter-individual variability. In fattening pigs, for example, some animals are more socially motivated than others (Hemsworth et al., 2011), and some animals tend to promote or limit social cohesion within their group through their expression of social nosing, aggression, or social proximity (Camerlink et al., 2014). Similarly, pigs show differing propensities to fight: the most aggressive individuals are typically more active and engaged in social interactions, while the least aggressive are less active and less engaged in social interactions (Mendl et al., 1992). Recently, in suckling piglets, we identified distinct social profiles based on levels of social involvement, with socially active animals (which initiate social interactions), socially inactive animals (which are rarely solicited), and “avoiders”, who are frequently solicited but do not respond to social approaches. These profiles were associated with individual characteristics such as sex, overall activity level, and health status (Clouard et al., 2022). This work confirms the existence of contrasting social profiles associated with individual characteristics or activity levels, a pattern also observed in other farm animals such as sheep (Miranda-de la Lama et al., 2019), goats (Miranda-de la Lama et al., 2011), and cows (Mülleder et al., 2003). Moreover, our findings suggest that certain social traits, such as “sociability” or “social motivation”, reflected in the frequency of social nosing or play, may be stable traits present from an early age. In contrast, social behaviours related to dominance or sex (e.g. aggression, avoidance) may be less stable in young animals and more shaped by experience (Turner, 2011; Clouard et al., 2022).

A better understanding of inter-individual variability in social behaviour, and in particular of social roles, could facilitate group management in livestock farming. For instance, Camerlink et al (2014) highlighted the influence of certain individuals on social cohesion, measured by inter-individual distances. Animals showing little social nosing, and characterised by many body lesions, high inactivity, and high weight appeared to reduce social cohesion within the group. In contrast, animals displaying more social nosing, and characterised by few body lesions, high activity, and low weight were more likely to approach conspecifics and promote social cohesion. Pig groups are also thought to be structured around leadership hierarchies, defined as the ability of an individual to influence the activities of others (Miranda-de la Lama & Mattiello, 2010). Certain animals tend to systematically initiate specific activities, with other members following (Ewbank, 1976). These leaders are not necessarily the largest or most dominant animals, but females tend to be leaders more often than males (Ewbank, 1976; Khatiwada et al., 2024). Characterising and identifying these leaders could facilitate livestock management, for example by promoting social learning through observation, such as when changing housing, introducing new technologies (e.g. automatic feed dispensers), or offering unfamiliar feeds. In goats, for example, it is recommended that leaders, who are often older animals, wear a bell to encourage group cohesion during grazing (Miranda-de la Lama & Mattiello, 2010).

A better characterisation of inter-individual variability in social behaviour could also have implications for genetic selection. Indeed, the identification of stable social traits suggests that it may be possible to select animals for desirable social traits (or against undesirable ones). Genetic phenotyping strategies based on social criteria have already been developed and tested to reduce aggression and other problematic social behaviours in livestock population, but these strategies have proven costly and difficult to apply in practice (Turner, 2011; Peden et al., 2018). Alternative approaches have been proposed, such as the genetic selection based on indirect genetic effects (Peden et al., 2018). These effects, also known as social or associative genetic effects, refer to the influence an individual’s genotype has on the phenotype of its group mates. This concept is based on the theory that an individual's performance is shaped not only by its own genotype, but also by the genotypes of the individuals it interacts with. Selecting animals with positive indirect genetic effects on productivity could help reduce undesirable social behaviours, such as aggression or tail biting, at group level (e.g. Camerlink et al., 2013). These strategies have the advantage of not requiring costly additional phenotyping, although estimates of these indirect effects are not yet clearly established (Peden et al., 2018).

As with genetic selection aimed at reducing aggression, gaining insight into social traits could allow for the selection of animals with high levels of sociality, tolerance, or cooperation, traits that may have significant benefits for both welfare and productivity. Improved social skills could give animals greater resilience to challenges such as social mixing, by lowering stress levels and improving performance. According to Camerlink et al.(2014), during social mixing, it may be more effective to include animals that cope well with social challenges, especially those that can quickly establish a stable hierarchy, rather than simply focusing on reducing aggression. Indirect genetic selection for animals with favourable social traits could also enhance the performance of conspecifics. Pigs with a positive social genetic profile have been shown to positively influence the growth of their group mates, suggesting beneficial effects at the group level (Nielsen et al., 2018). These effects may also depend on the degree of familiarity between individuals (Bijma, 2014).

Conclusion

The social behaviour of pigs has been extensively studied by the scientific community, providing essential insights into the interactions between social behaviour, the social environment, husbandry practices, and animal welfare (Figure 4). However, more knowledge is needed about non-agonistic interactions, particularly to better understand their role in social communication and affiliative relationships, to identify the impact of husbandry practices on these behaviours, and to determine their importance for maintaining animal welfare in pig farming. A deeper understanding of pig social behaviour could lead to the development of innovative management practices. For example, animals could be given more opportunities to engage in positive interactions, maintain social bonds, or choose their social partners. Early socialisation programmes, such as mixing different litters before weaning, could also be implemented to promote the development of socially competent individuals better equipped to face future challenges. Finally, the ability of animals to express a full social repertoire and live in stable groups appears to be of fundamental importance for maintaining welfare in livestock systems and should be a key consideration in the design of future farming systems.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Elodie Merlot and Armelle Prunier for their careful review of this summary and their pertinent suggestions, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their enlightened comments. All this feedback has greatly improved the quality of the article.

This article was initially translated from French to English using www.DeepL.com/Translator, and subsequently revised and refined by Caroline Clouard-Mésange to improve clarity, accuracy and phrasing.

Notes

- 1.

References

- Andersen, I. L., Andenæs, H., Bøe, K. E., Jensen, P., & Bakken, M. (2000). The effects of weight asymmetry and resource distribution on aggression in groups of unacquainted pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 68(2), 107-120. doi:10.1016/s0168-1591(00)00092-7

- ANSES. (2018). Bien-être animal : contexte, définition et évaluation (Avis de l’ANSES, saisine no 2016-SA-0288). Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation de l’environnement et du travail. https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/avis-de-lanses-relatif-au-bien-etre-animal-contexte-definition-et-evaluation

- Beattie, V. E., O’Connell, N. E., & Moss, B. W. (2000). Influence of environmental enrichment on the behaviour, performance and meat quality of domestic pigs. Livestock Production Science, 65(1-2), 71-79. doi:10.1016/S0301-6226(99)00179-7

- Bekoff, M. (1984). Social Play Behavior. BioScience, 34(4), 228-233. doi:10.2307/1309460

- Bijma, P. (2014). The quantitative genetics of indirect genetic effects: a selective review of modelling issues. Heredity, 112(1), 61-69. doi:10.1038/hdy.2013.15

- Boissy, A., & Le Neindre, P. (1990). Social influences on the reactivity of heifers: Implications for learning abilities in operant conditioning. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 25(1-2), 149-165. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(90)90077-Q

- Boissy, A., Manteuffel, G., Jensen, M. B., Moe, R. O., Spruijt, B., Keeling, L. J., Winckler, C., Forkman, B., Dimitrov, I., Langbein, J., Bakken, M., Veissier, I., & Aubert, A. (2007). Assessment of positive emotions in animals to improve their welfare. Physiology & Behavior, 92(3), 375-397. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.003

- Bolhuis, J. E., Schouten, W. G. P., Schrama, J. W., & Wiegant, V. M. (2005). Behavioural development of pigs with different coping characteristics in barren and substrate-enriched housing conditions. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 93(3-4), 213-228. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.01.006

- Brent, L. J. N., Chang, S. W. C., Gariépy, J.-F., & Platt, M. L. (2014). The neuroethology of friendship. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1316(1), 1-17. doi:10.1111/nyas.12315

- Bulens, A., Van Beirendonck, S., Van Thielen, J., Buys, N., & Driessen, B. (2017). Hiding walls for fattening pigs: Do they affect behavior and performance? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 195, 32-37. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2017.06.009

- Camerlink, I., & Turner, S. P. (2013). The pig’s nose and its role in dominance relationships and harmful behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 145(3-4), 84-91. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2013.02.008

- Camerlink, I., Turner, S. P., Bijma, P., & Bolhuis, J. E. (2013). Indirect genetic effects and housing conditions in relation to aggressive behaviour in pigs. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e65136. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065136

- Camerlink, I., Turner, S. P., Ursinus, W. W., Reimert, I., & Bolhuis, J. E. (2014). Aggression and affiliation during social conflict in pigs. PLoS ONE, 9(11), e113502. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113502

- Camerlink, I., Reimert, I., & Bolhuis, J. E. (2016). Intranasal oxytocin administration in relationship to social behaviour in domestic pigs. Physiology & Behavior, 163, 51-55. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.054

- Camerlink, I., Proßegger, C., Kubala, D., Galunder, K., & Rault, J.-L. (2021). Keeping littermates together instead of social mixing benefits pig social behaviour and growth post-weaning. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 235, 105230. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105230

- Camerlink, I., Scheck, K., Cadman, T., & Rault, J.-L. (2022). Lying in spatial proximity and active social behaviours capture different information when analysed at group level in indoor-housed pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 246, 105540. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105540

- Clouard, C., & Bolhuis, J. E. (2017). Olfactory behaviour in farm animals. In B. L. Nielsen (Ed.) Olfaction in animal behaviour and welfare (161-175). CABI Books. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391599.0161

- Clouard, C., Resmond, R., Prunier, A., Tallet, C., & Merlot, E. (2022). Exploration of early social behaviors and social styles in relation to individual characteristics in suckling piglets. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 2318. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-06354-w

- Clouard, C., Resmond, R., Vesque-Annear, H., Prunier, A., & Merlot, E. (2023). Pre-weaning social behaviours and peripheral serotonin levels are associated with behavioural and physiological responses to weaning and social mixing in pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 259, 105833. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2023.105833

- Clouard, C., Chambeaud, J., & Merlot, E. (2024a). Exploration of positive social relationships in group-housed gestating sows. 9th International Conference on the Welfare Assessment of Animals at Farm Level (WAFL), Florence Italy. https://hal.science/hal-04693554v1

- Clouard, C., Foreau, A., Goumon, S., Tallet, C., Merlot, E., & Resmond, R. (2024b). Evidence of stable preferential affiliative relationships in the domestic pig. Animal Behaviour, 213, 95-105. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2024.04.009

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310-357. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- D’Eath, R. B. (2005). Socialising piglets before weaning improves social hierarchy formation when pigs are mixed post-weaning. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 93(3-4), 199-211. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2004.11.019

- Dobao, M. T., Rodrigañez, J., & Silio, L. (1985). Choice of companions in social play in piglets. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 13(3), 259-266. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(85)90049-8

- Durrell, J. L., Sneddon, I. A., O’Connell, N. E., & Whitehead, H. (2004). Do pigs form preferential associations? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 89(1-2), 41-52. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2004.05.003

- Estevez, I., Andersen, I.-L., & Nævdal, E. (2007). Group size, density and social dynamics in farm animals. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 103(3-4), 185-204. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.025

- Ewbank, R. (1976). Social hierarchy in suckling and fattening pigs: A review. Livestock Production Science, 3(4), 363-372. doi:10.1016/0301-6226(76)90070-1

- Farm Animal Welfare Council. (1993). Second report on priorities for research and development in farm animal welfare. Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

- Ferguson, J. N., Aldag, J. M., Insel, T. R., & Young, L. J. (2001). Oxytocin in the medial amygdala is essential for social recognition in the mouse. The Journal of Neuroscience, 21(20), 8278-8285. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08278.2001

- Foris, B., Haas, H.-G., Langbein, J., & Melzer, N. (2021). Familiarity influences social networks in dairy cows after regrouping. Journal of Dairy Science, 104(3), 3485-3494. doi:10.3168/jds.2020-18896

- Gonyou, H. W. (2001). The social behaviour of pigs. In L. J. Keeling & H. W. Gonyou (Eds.), Social behaviour in farm animals (pp. 147-176). CABI Books. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851993973.0147

- Goumon, S., Illmann, G., Leszkowová, I., Dostalová, A., & Cantor, M. (2020). Dyadic affiliative preferences in a stable group of domestic pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 230, 105045. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2020.105045

- Graves, H. B. (1984). Behavior and ecology of wild and feral swine (Sus Scrofa). Journal of Animal Science, 58(2), 482-492. doi:10.2527/jas1984.582482x

- Hellekant, G., & Danilova, V. (1999). Taste in domestic pig, Sus scrofa. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 82(1), 8-24. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0396.1999.00206.x

- Hemsworth, P. H., Smith, K., Karlen, M. G., Arnold, N. A., Moeller, S. J., & Barnett, J. L. (2011). The choice behaviour of pigs in a Y maze: Effects of deprivation of feed, social contact and bedding. Behavioural Processes, 87(2), 210-217. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2011.03.007

- Horback, K. (2014). Nosing around: play in pigs. Animal Behavior and Cognition, 1(2), 186-196. doi:10.12966/abc.05.08.2014

- Hötzel, M. J., Pinheiro Machado, L. C., Wolf, F. M., & Costa, O. A. D. (2004). Behaviour of sows and piglets reared in intensive outdoor or indoor systems. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 86(1-2), 27-39. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2003.11.014

- Jensen, P. (1980). An ethogram of social interaction patterns in group-housed dry sows. Applied Animal Ethology, 6(4), 341-350. doi:10.1016/0304-3762(80)90134-0

- Jensen, P. (1986). Observations on the maternal behaviour of free-ranging domestic pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 16(2), 131-142. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(86)90105-X

- Jensen, P. (1988). Maternal behaviour and mother–Young interactions during lactation in free-ranging domestic pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 20(3-4), 297-308. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(88)90054-8

- Jensen, P., & Recén, B. (1989). When to wean – Observations from free-ranging domestic pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 23(1-2), 49-60. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(89)90006-3

- Jensen, P., Stangel, G., & Algers, B. (1991). Nursing and suckling behaviour of semi-naturally kept pigs during the first 10 days postpartum. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 31(3-4), 195-209. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(91)90005-I

- Jensen, P., & Stangel, G. (1992). Behaviour of piglets during weaning in a seminatural enclosure. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 33(2-3), 227-238. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(05)80010-3

- Jones, J. B., Wathes, C. M., Persaud, K. C., White, R. P., & Jones, R. B. (2001). Acute and chronic exposure to ammonia and olfactory acuity for n-butanol in the pig. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 71(1), 13-28. doi:10.1016/s0168-1591(00)00168-4

- Kanitz, E., Hameister, T., Tuchscherer, M., Tuchscherer, A., & Puppe, B. (2014). Social support attenuates the adverse consequences of social deprivation stress in domestic piglets. Hormones and Behavior, 65(3), 203-210. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.01.007

- Khatiwada, S., Turner, S. P., Farish, M., & Camerlink, I. (2024). Leadership amongst pigs when faced with a novel situation. Behavioural Processes, 222, 105099. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2024.105099

- Kristensen, H. H., Jones, R. B., Schofield, C. P., White, R. P., & Wathes, C. M. (2001). The use of olfactory and other cues for social recognition by juvenile pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 72(4), 321-333. doi:10.1016/s0168-1591(00)00209-4

- Lanthony, M., Danglot, M., Špinka, M., & Tallet, C. (2022). Dominance hierarchy in groups of pregnant sows: Characteristics and identification of related indicators. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 254, 105683. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2022.105683

- Lopes, M. M., Clouard, C., Chambeaud, J., Brien, M., Villain, N., Gerard, C., Herault, F., Vincent, A., Louveau, I., Resmond, R., & Merlot, E. (2023). Impact de l’enrichissement du milieu de vie des truies gestantes sur leur comportement et la réponse transcriptionnelle de leurs cellules immunitaires sanguines. 55e Journées de la Recherche Porcine, Saint-Malo. doi:10.1016/j.anscip.2023.06.012

- Makagon, M. M., McCowan, B., & Mench, J. A. (2012). How can social network analysis contribute to social behavior research in applied ethology? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 138(3-4), 152-161. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2012.02.003

- Meese, G. B., & Ewbank, R. (1973). The establishment and nature of the dominance hierarchy in the domesticated pig. Animal Behaviour, 21(2), 326-334. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(73)80074-0

- Mendl, M., Zanella, A. J., & Broom, D. M. (1992). Physiological and reproductive correlates of behavioural strategies in female domestic pigs. Animal Behaviour, 44(6), 1107-1121. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80323-9

- Metz, J. H. M., & Gonyou, H. W. (1990). Effect of age and housing conditions on the behavioural and haemolytic reaction of piglets to weaning. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 27(4), 299-309. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(90)90126-X

- Miranda-de la Lama, G. C., & Mattiello, S. (2010). The importance of social behaviour for goat welfare in livestock farming. Small Ruminant Research, 90(1-3), 1-10. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2010.01.006

- Miranda-de la Lama, G. C., Sepúlveda, W. S., Montaldo, H. H., María, G. A., & Galindo, F. (2011). Social strategies associated with identity profiles in dairy goats. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 134(1-2), 48-55. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2011.06.004

- Miranda-de la Lama, G. C., Pascual-Alonso, M., Aguayo-Ulloa, L., Sepúlveda, W. S., Villarroel, M., & María, G. A. (2019). Social personality in sheep: Can social strategies predict individual differences in cognitive abilities, morphology features, and reproductive success? Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 31, 82-91. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2019.03.005

- Mülleder, C., Palme, R., Menke, C., & Waiblinger, S. (2003). Individual differences in behaviour and in adrenocortical activity in beef-suckler cows. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 84(3), 167-183. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2003.08.007

- Newberry, R. C., & Wood-Gush, D. G. M. (1985). The suckling behaviour of domestic pigs in a semi-natural environment. Behaviour, 95(1-2), 11-25. doi:10.1163/156853985x00028

- Newberry, R. C., & Wood-Gush, D. G. M. (1986). Social relationships of piglets in a semi-natural environment. Animal Behaviour, 34(5), 1311-1318. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80202-0

- Newberry, R. C., Wood-Gush, D. G. M., & Hall, J. W. (1988). Playful behaviour of piglets. Behavioural Processes, 17(3), 205-216. doi:10.1016/0376-6357(88)90004-6

- Nielsen, H. M., Ask, B., & Madsen, P. (2018). Social genetic effects for growth in pigs differ between boars and gilts. Genetics Selection Evolution, 50(1), 4. doi:10.1186/s12711-018-0375-0

- O’Connor, E. A., Parker, M. O., McLeman, M. A., Demmers, T. G., Lowe, J. C., Cui, L., Davey, E. L., Owen, R. C., Wathes, C. M., & Abeyesinghe, S. M. (2010). The impact of chronic environmental stressors on growing pigs, Sus scrofa (Part 1): stress physiology, production and play behaviour. Animal, 4(11), 1899-1909. doi:10.1017/S1751731110001072

- Oostindjer, M., van den Brand, H., Kemp, B., & Bolhuis, J. E. (2011). Effects of environmental enrichment and loose housing of lactating sows on piglet behaviour before and after weaning. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 134(1-2), 31-41. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2011.06.011

- Parker, M. O., O’Connor, E. A., McLeman, M. A., Demmers, T. G. M., Lowe, J. C., Owen, R. C., Davey, E. L., Wathes, C. M., & Abeyesinghe, S. M. (2010). The impact of chronic environmental stressors on growing pigs, Sus scrofa (Part 2): social behaviour. Animal, 4(11), 1910-1921. doi:10.1017/S1751731110001084

- Pearce, E., Wlodarski, R., Machin, A., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2017). Variation in the β-endorphin, oxytocin, and dopamine receptor genes is associated with different dimensions of human sociality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(20), 5300-5305. doi:10.1073/pnas.1700712114

- Peden, R. S. E., Turner, S. P., Boyle, L. A., & Camerlink, I. (2018). The translation of animal welfare research into practice: The case of mixing aggression between pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 204, 1-9. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2018.03.003

- Petersen, H. V., Vestergaard, K., & Jensen, P. (1989). Integration of piglets into social groups of free-ranging domestic pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 23(3), 223-236. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(89)90113-5

- Podgórski, T., Lusseau, D., Scandura, M., Sönnichsen, L., & Jędrzejewska, B. (2014). Long-lasting, kin-directed female interactions in a spatially structured wild boar social network. PLoS ONE, 9(6), e99875. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099875

- Puppe, B., Langbein, J., Bauer, J., & Hoy, S. (2008). A comparative view on social hierarchy formation at different stages of pig production using sociometric measures. Livestock Science, 113(2-3), 155-162. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2007.03.004

- Rault, J.-L. (2012). Friends with benefits: Social support and its relevance for farm animal welfare. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 136, 1-14. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2011.10.002

- Rault, J.-L. (2016a). Social interaction patterns according to stocking density and time post-mixing in group-housed gestating sows. Animal Production Science, 57(5), 896-902. doi:10.1071/AN15415

- Rault, J.-L. (2016b). Effects of positive and negative human contacts and intranasal oxytocin on cerebrospinal fluid oxytocin. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 69, 60-66. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.03.015

- Rault, J.-L. (2019). Be kind to others: Prosocial behaviours and their implications for animal welfare. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 210, 113-123. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2018.10.015

- Rault, J.-L., Newberry, R. C., & Šemrov, M. Z. (2023). Editorial: Positive welfare: from concept to implementation. Frontiers in Animal Science, 4. doi:10.3389/fanim.2023.1289659