Interest of in vitro cultures of stem cells and organoids in toxicological studies (Full text available in English)

Header

The use of both animal models and cell lines can be problematic when conducting biological, and in particular, toxicological studies. Firstly, there can be discrepancies between the response of the animal model used, and that of the actual species being studied, and secondly, transformed cell lines can give a response that is far removed from physiology. The use of stem cells and organoids in vitro is a promising solution to some of these difficulties.

Introduction

People are increasingly concerned about the toxicity of our environment and its impact on our health. Toxicity corresponds to the "introduction or bio-accumulation of a toxic substance in the body", and the aim of toxicology is therefore to understand and predict the undesirable effects of drugs and other xenobiotics. A xenobiotic is defined as a foreign molecule present in a living organism; it is neither produced by the organism itself nor introduced through its natural diet. A xenobiotic may be capable of disrupting the normal functioning of an individual and lead to harmful effects on the organism. These substances may be environmental pollutants, food additives or medicines.

The many environmental pollutants to which we are exposed can become part of the trophic chain, mostly starting with plants, then followed by primary and secondary predators, the category to which humans belong. These environmental toxins include Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and dioxins. These molecules accumulate at cellular level, particularly in adipocytes, making them very difficult to eliminate (La Rocca and Mantovani, 2006). Other types of pollutants, such as heavy metals and pesticides, can also pose health problems. Natural toxins can also be a problem, for example poisoning by cyanobacterial toxins is becoming more frequent due to global warming (Abeysiriwardena et al., 2018).

Medicines are also considered to be xenobiotics and are therefore very much involved in toxicological studies. Medicines are essentially bioactive substances that can be toxic if they are not used correctly or if they are not adapted to the target organism. For example, substances developed for human use are not necessarily compatible with veterinary use. Medicines bought over the counter can be very dangerous for pets. Aspirin and ibuprofen are two examples of pharmaceutical compounds that are highly toxic for cats and dogs, and can lead to coma. The enzymes that break down these molecules in the body are not present in these species: severe liver and kidney complications can occur in dogs with doses as low as 50 mg/kg (Tauk and Foster, 2016). Another concrete example of inter-species differences in susceptibility is when paracetamol-loaded mice placed on the island of Guam were able to greatly reduce the number of Boiga irregularis snake specimens (Johnston et al., 2002).

Toxicological studies are therefore necessary to assess the risk-benefit ratio of future medicines and the possible toxicity of pesticides on non-target species before or after they are marketed.

From an ethical point of view, xenobiotics cannot be tested on humans. Only clinical evaluations, psychometric or neurosensory tests, and electrophysiological or imaging examinations can be carried out. Various experimental approaches have therefore been developed, including in vivo, in vitro, and in silico models.

In silico models are computer experiments that store, compile, exchange and use information from previously conducted in vitro and in vivo experiments. These numerical methods make it possible to predict the toxicokinetics of a molecule, thereby reducing the cost and duration of studies. Various in silico models have been developed to describe the relationship between the chemical structure and the activity of a compound, namely Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) models and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. In the classical, or mono-compartmental toxicokinetic model, it is possible to predict the concentration of the toxicant as a function of time and exposure dose. The physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model relies on real knowledge of the system by subdividing the organism into compartments linked by a circulating fluid (Coumoul et al., 2023).

The most commonly used in vivo models are rats, mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, and dwarf pigs, due to their physiological and molecular similarities to humans. However, the effects of a toxic substance may vary according to the time of exposure, the dose, and the route of exposure. In accordance with OECD guidelines, four protocols are used in toxicological studies to test acute toxicity, sub-acute toxicity, sub-chronic toxicity, and chronic toxicity (Coumoul et al., 2023). For drugs and Marketing Authorisation (MA), pre-clinical trials are conducted on model organisms (usually rodents) under experimental conditions, and clinical trials are conducted on the target species.

Animal experimentation makes it possible to study the effects of a toxic molecule on the physiology and metabolism of a single individual, thereby predicting toxicity in humans. The toxicological impact of a substance is generally studied according to the ADME concept: Absorption, Distribution in the body, Metabolisation, and Elimination. These processes reflect an organism's ability to adapt to, bio-accumulate or eliminate a xenobiotic. From one individual to another and from one species to another, there can be significant variations, resulting in varied responses to a toxic substance or drug treatment.

These in vivo tests require a large number of animals, and the 3Rs principle (Replace/Reduce/Refine) defined in 1959 by Russell and Burch to improve animal welfare has become one of the fundamental principles of research underpinned by the requirements of Directive 2010/63/EC1. The 3Rs rule consists of replacing animal experimentation where possible, and optimising the replacement methodologies to guarantee high quality scientific results. The European REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and restriction of CHemicals) regulation for the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemical substances also favours in vitro and in silico methods (Jean-Quartier et al., 2018).

This is where the importance of the in vitro methods that have developed over the last few decades comes into play. There are two main cell culture models for testing the toxicology of xenobiotics.

Primary cultures are derived directly from cells in an organism. The cells are isolated by mechanical and/or chemical dissociation, usually using enzymes. They have a limited number of cell divisions, making these culture models fairly close to the physiological state of cells in the organism. Among primary cultures, stem cell cultures are a valuable tool, particularly in medicine. These are undifferentiated, pluripotent cells that can give rise to different cell types depending on the culture medium. This type of culture has expanded rapidly with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): these cells, discovered in 2006 by Shinya Yamanaka (winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2012), enable different cell types to be obtained from a single somatic cell. In contrast cell lines are derived from cancer cells immortalised by transfection of a viral oncogene from cultures of primary cells. In this case, the number of cell divisions is close to infinite and the same culture can be maintained for a long time without any risk of drift. This makes it possible to obtain reproducible results quickly, and at lower cost.

Two main types of cell cultures are used: cultures in monolayers of cells in two dimensions (2D), and cultures in 3 dimensions (3D). While 2D culture promotes proliferation and therefore its study, it does not reproduce all the conditions of the living organism (Yamada and Cukierman, 2007; Costa et al., 2016). 3D culture enables cell differentiation to be better preserved via interactions with the environment. 3D co-culture models enable the association of different cell types, thereby favouring the interactions and intercellular communications normally present in vivo. Thanks to these in vitro models, numerous toxicological parameters can be assessed in order to study the impact of a compound and thus determine its cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, changes in energy metabolism, or differentiation processes. The use of human cell lines allows data to be extrapolated to humans.

Thus, out of all the different cell models, primary stem cell cultures or organoid cultures (see paragraph 2) appear to be good compromises, as they allow a reduction in the number of animals used, and a decrease of certain experimental biases. These cell culture models are particularly interesting for studying the toxic effects of environmental pollutants and the underlying cellular mechanisms.

1. Toxicology and environmental pollutants

Methodological approaches

Since the 20th century, numerous health scandals have led to the introduction of stricter regulations on xenobiotics, including heavy metals such as mercury, pesticides such as glyphosate and endocrine disrupters such as phthalates. Concepts have had to evolve due to the large number of chemical substances to be assessed and the need to limit the use of animal experiments. Toxicology now incorporates new parameters for a more detailed assessment of the risks associated with our environment, such as dose-response relationships (LOAEL: Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level; NOAEL: No Observable Adverse Effect Level) and Toxicological Reference Values (TRV). There has also been a move towards a predictive toxicology/ecotoxicology framework, with the aim of establishing credible causal relationships and developing quantitative extrapolation tools/models. This approach has led to the development of the concept of Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOP).

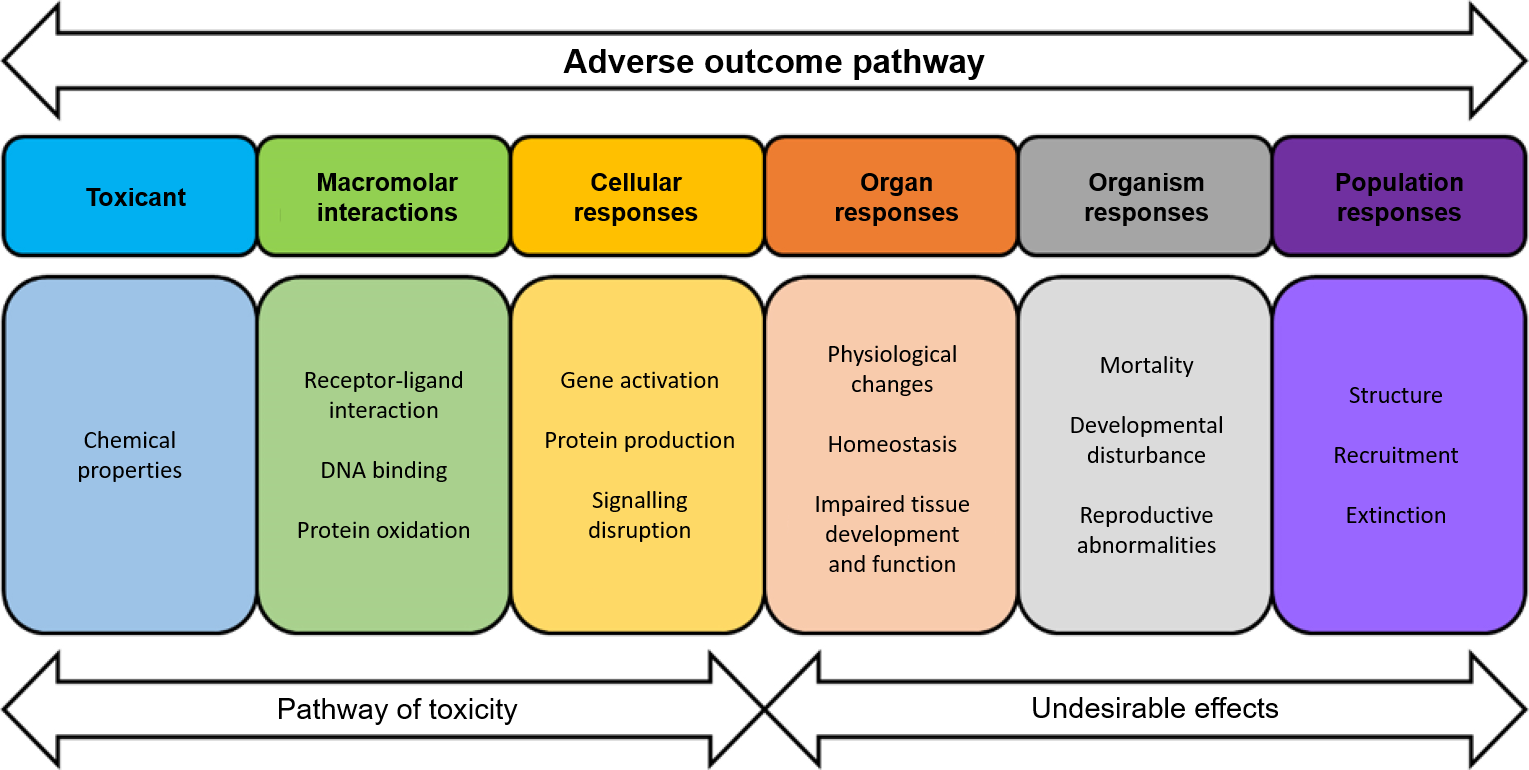

An AOP is a conceptual construct (Figure 1) describing existing knowledge of the causal link between a direct triggering molecular event and the production of an adverse effect for an individual (Ankley et al., 2010).

An AOP therefore corresponds to a series of events at different biological levels: molecular, cellular and tissue, on an individual or at the scale of a population. It makes it possible to characterise, organise and define predictive relationships between key events and adverse reactions relevant to risk assessment. The information can be based on in vitro, in vivo or in silico models (Ankley et al., 2010; Coumoul et al., 2023). The AOP concept makes it possible to identify the tests to be carried out in vitro or in vivo more quickly, and knowledge of the chemical and biochemical structure of the pollutant makes it possible to identify the pathways that are likely to be disturbed.

Figure 1: Concept of an AOP (after Ankley et al., 2010).

Early exposure and its impact on development

It is essential to take the period of exposure (earliness), the toxicity of low doses, and the chronic exposure into account. Several factors may interact with these time windows, and the consequences may not necessarily be immediate, but can manifest themselves later on in life (Andersen, 2003; Hale et al., 2014; Vaudin et al., 2022). There is increasing evidence that many compounds inhibit and impact normal foeto-embryonic development (methylmercury, dioxins, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls - PCBs, nanoparticles, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons - PAHs; heavy metals). These chemical compounds are found in the environment and in food, alone or mixed, and can act as neurotoxic agents and/or neuro-endocrine disruptors via their cytotoxic, pro-inflammatory, and pro-oxidant effects (Roegge and Schantz, 2006; Dietert, 2012; Dridi et al., 2014).

If we take the example of the nervous system during the pre- and postnatal periods, the developing brain displays structural and cellular set-ups that are highly sensitive and vulnerable to the risks of toxic exposure, in particular environmental contaminants (Andersen, 2003; Ingber and Pohl, 2016). Maternal lifestyle, along with its various environmental and dietary exposures, is one of the most important factors interfering with the development of the immature brain (Lauritzen et al., 2001; Fall, 2009; Hale et al., 2014). Maternal pre- and/or postnatal diet may alter or reprogram brain development through epigenetic regulation of inflammatory pathways such as hypomethylation of inflammatory genes, deregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and activation of microglial cells that induce inflammatory mechanisms by producing inflammatory pro-cytokines (Spencer, 2013).

The deregulations of cellular metabolism induced by environmental exposures could condition a number of late effects throughout life, with an increased risk of the onset of pathologies including neuropsychiatric disorders, such as behavioural disorders, and cognitive and neurological deficits (neurodegenerative diseases) in adulthood (Andersen, 2003; Bilbo and Schwarz, 2009; Bolton and Bilbo, 2014).

These disturbances may be of maternal, placental and/or foetal origin and may act differentially and selectively between the sexes (Hale et al., 2014; Hagberg et al., 2015). Pollutants to which individuals are exposed early can cross protective barriers such as the placenta, the intestine and the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and also be available in breast milk, thus causing perinatal brain reprogramming via early inflammation (Li et al., 2013).

Multiple exposures and their impact on development

A major challenge is the assessment of the health risks of multiple exposures to a mixture (cocktail) of chemical micro-contaminants from the environment and food. Using an in vivo mouse model, it has been shown that perinatal exposure to a mixture of PCBs at low environmental doses induces oxidative stress in adult mice, which is correlated with disturbances to social behaviour and an increase in anxiety; these effects are sex- and age-dependent (Karkaba et al., 2017). This study shows that there is a link between endocrine effects following exposure to this mixture of pollutants and abnormal social behaviour in offspring. In addition, in 2022 an in vivo study on adult mice demonstrated that exposure to a mixture of pollutants (phthalates) present in the environment could promote the development of neurodegenerative diseases and disrupt nerve cell function by disrupting the glio-neurovascular axis (Ahmadpour et al., 2022).

These deleterious effects, as well as inflammatory and oxidative stresses early in life, may therefore be plausible causal factors for the appearance of behavioural disorders observed in animals, as shown in the mouse model for depression. Hyperactivity in middle-aged adult mice and cognitive impairment observed only in middle-aged female offspring have also been reported. The latter point suggests that sex plays an important role in determining the nature of the resulting alterations (Dridi et al., 2021).

2. Limitations of in vivo models and development of in vitro models

The various experimental tests set up to study the impact of these exposures often involve the use of animal models during gestation (in utero exposure), and also during lactation (Laugeray et al., 2017). In addition, observations have been carried out on multiple systemic functions, which in turn increases the number of animals used. When it comes to studying the toxicology of xenobiotics on livestock, wild animals, or humans, these in vivo studies become extremely complicated to implement for ethical and financial reasons. In line with AOPs and the 3Rs rule, in vitro methods are commonly used to try to explain the underlying molecular mechanisms. In addition, more simplified and rapid models supported by data processing and modelling tools are eagerly awaited by the scientific community. With technological and scientific advances, in vitro models are being combined with advanced 'bio-omics' tools: genomics to study genes and epigenetic modifications, transcriptomics to study RNA molecules, proteomics to study proteins, and metabolomics to study metabolomic responses (Karahahil, 2016; Pieters et al., 2021). These techniques generate a great deal of data and help to make predictive assessment faster and more reliable for characterising the danger of these exposures (D'Almeida et al., 2020). The wide range of data generated by these models can be analysed, and computer tools can be used to highlight the high significance of the results obtained in comparison with data obtained from in vivo animal tests.

2.1. The use of stem cells as an in vitro study model

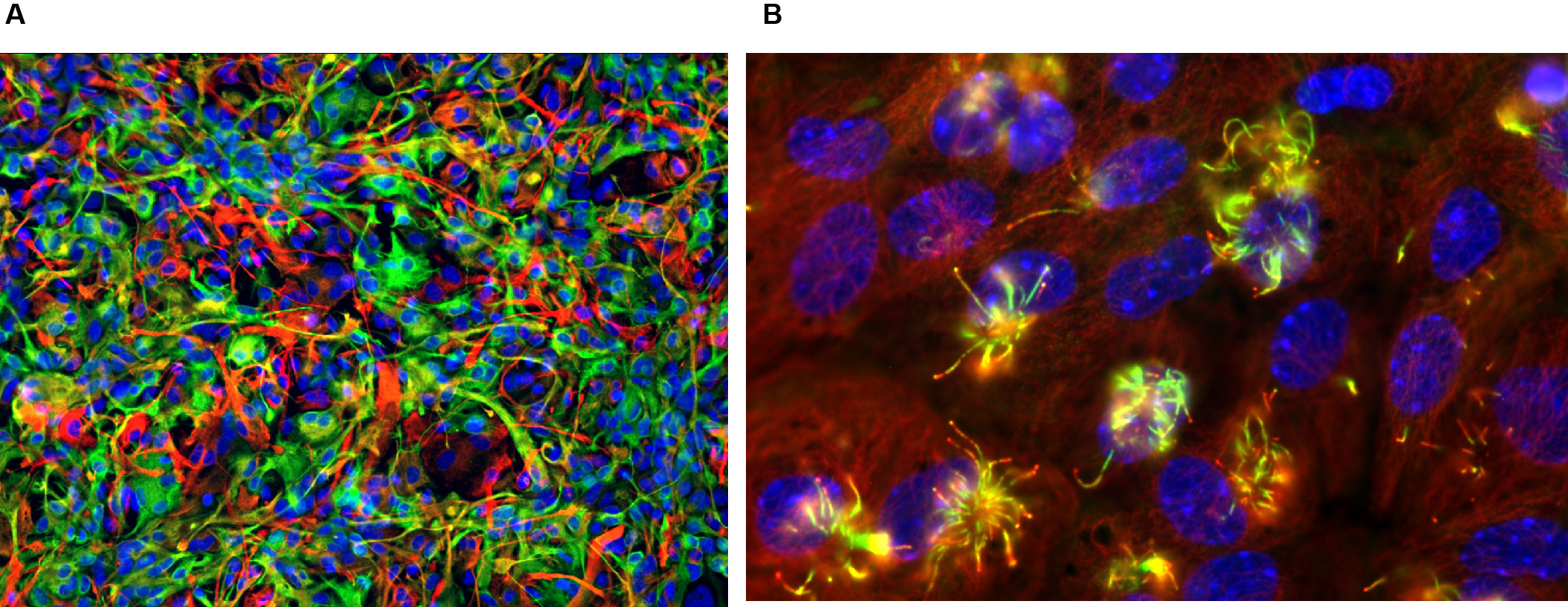

Large-scale in vitro toxicological tests on cell differentiation or to establish NOAELs and LOAELs have been made possible by advances in research and fundamental knowledge of stem cells, as well as the associated technological advances. Embryonic stem (ES) cells are characterised by their ability to self-renew and by their pluripotency, i.e. the ability to give rise to differentiated cell lines (Jervis et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021). It has been shown that these stem cells cultured in vitro with the required growth and differentiation factors, in the presence of extracellular matrix components, can proliferate while retaining their 'stemness'. It is also possible to use protocols involving iPSCs: for these cells, dedifferentiation of a somatic cell into a stem cell is induced. It is then possible to redirect their differentiation, for example into Neural Stem Cells (NSC) (Figure 2). They can also be used to produce self-organising three-dimensional (3D) structures (described below).

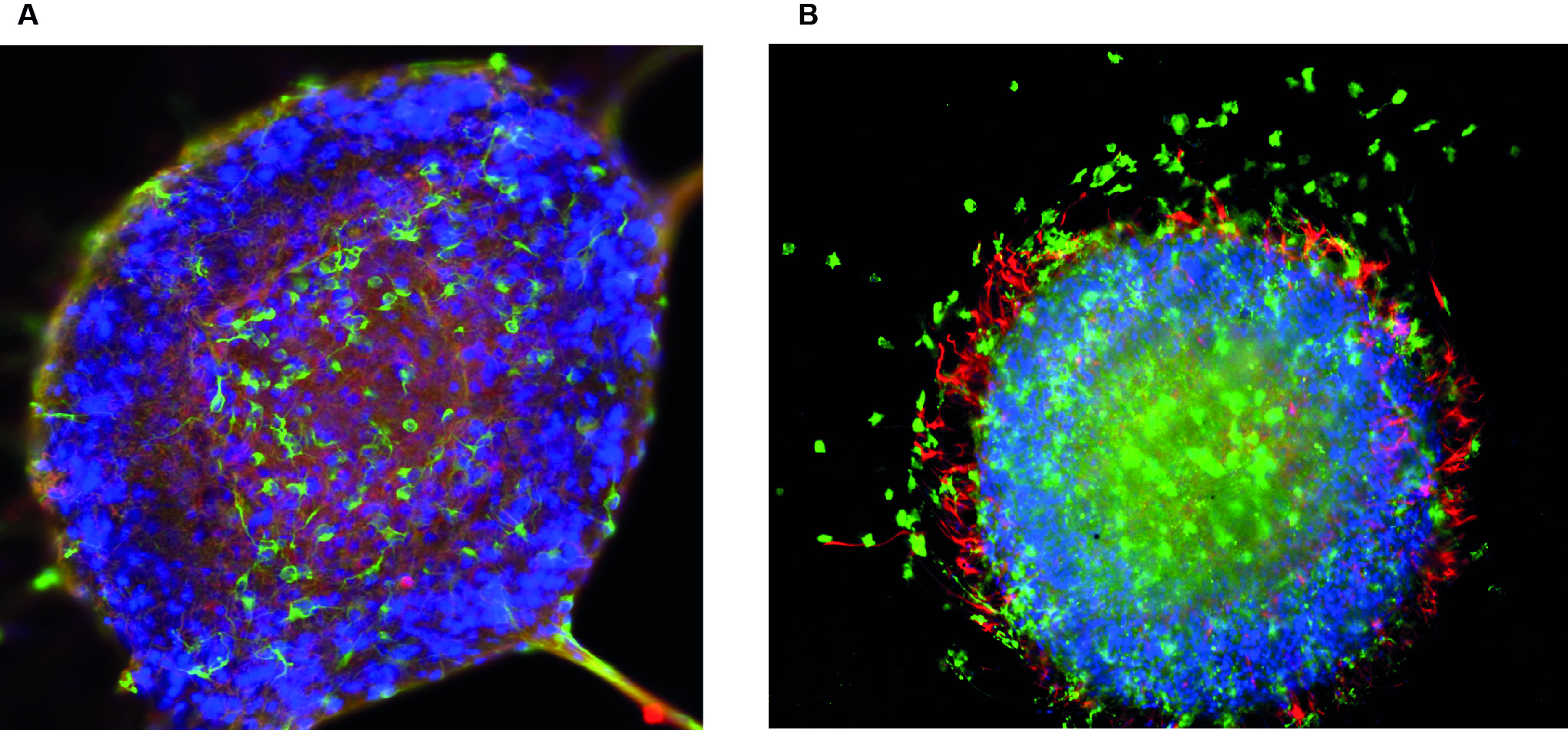

Figure 2: Brain stem cell (NSC) cultures.

A: Fluorescence immunocytology photograph of an NSC culture before differentiation. NSCs are made up of three populations: in orange, GFAP (Glial fibrillary acidic protein)+/Nestin+ cells (stem cells proper, B1); in green, Nestin+ cells (intermediate C progenitors), in red, GFAP+ cells (Astrocytes); in blue, DAPI (cell nuclei).

B: Photograph of an NSC culture after differentiation: here, the differentiation into ependymocytes, which occurs in the absence of growth factors. Red: actin, green: polyglutamylated tubulin. The ciliated tufts of the ependymocytes are highly polyglutamylated. (Feat-Vetel et al., 2018)

2.2. Use of stem cells for 2D cultures

2D ES cell culture models are already a good tool for assessing the toxicity and impact of a drug, a mixture of micro-contaminants, or even the impact of toxins on cellular function (Chen et al., 2021). A wide range of data can be obtained, for example by analysing cell differentiation capacities, quantifying different biomarkers using molecular tools involving 'omics' approaches, or collecting biochemical data (Danoy et al., 2021). The main objective of this type of approach is to enrich the scientific data concerning the impact of exposure to mixtures of contaminants, in order to advance studies of toxicity mechanisms, improve the prediction of these toxic effects, and contribute to strengthening risk assessment and regulation in terms of environmental and food safety.

The results can also help us to understand the aetiology, allowing the consequences of early and chronic exposure to low-dose environmental contaminants to be assessed using a reduced, reliable and rapid model rather than in vivo models. The data generated can then also help to provide additional data for establishing exposure limit values (toxicological reference values) for different mixtures of contaminants. Cell cultures of these stem cells are therefore valuable models for studying the effects of xenobiotics.

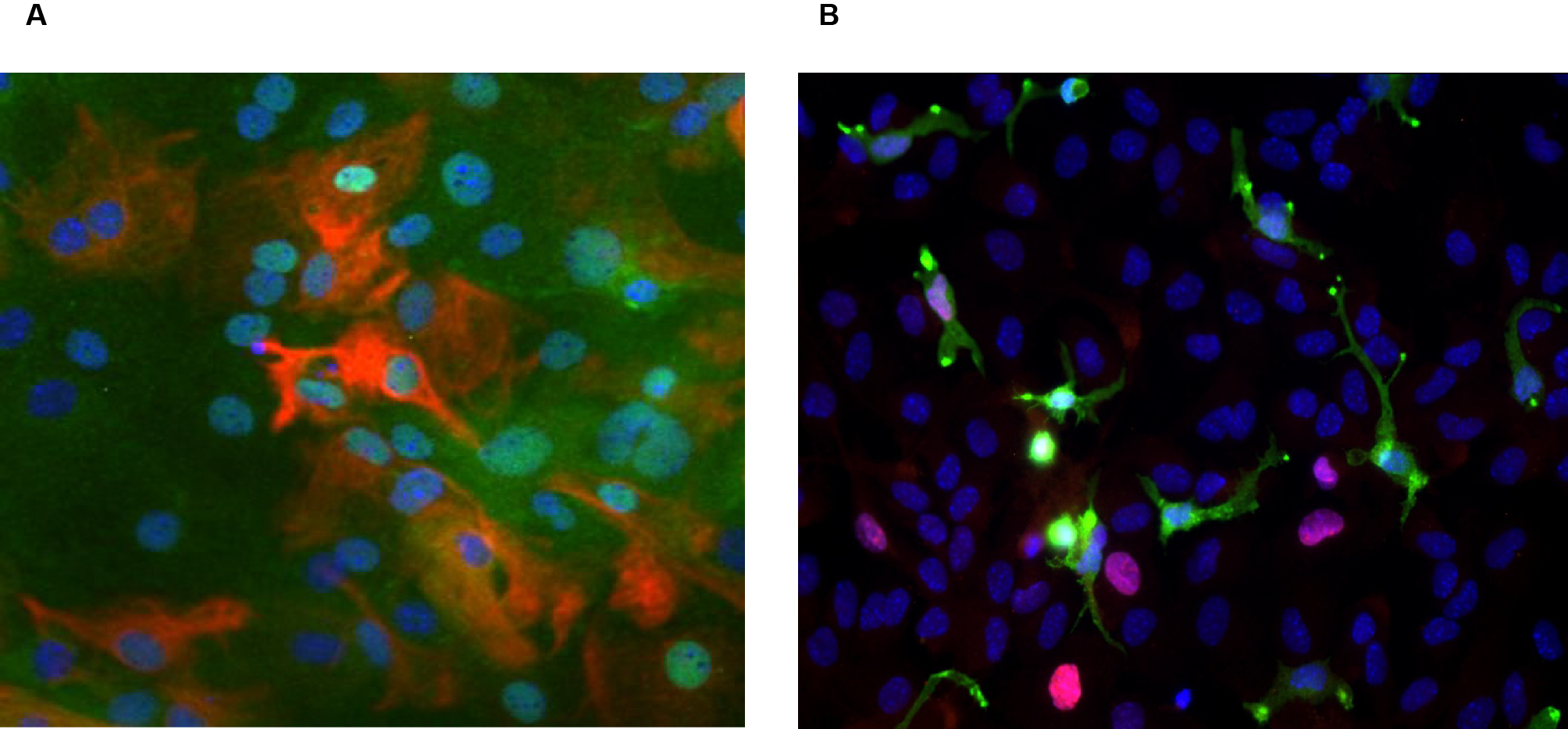

We set up an NSC culture model in the laboratory which enables us to assess the potential deleterious effects of environmental toxicants at the cellular level (Feat-Vetel et al., 2018; Méresse et al., 2022). For example, we can visualize the translocation of the nuclear factor NF-κB, which would be difficult with an in vivo model (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Immunocytological applications of NSC cultures.

A: Demonstration of nuclear translocation of NF-κB after stimulation with a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) representing a pro-inflammatory signal. The NF-κB factor is present at cytoplasmic level: in the presence of a pro-inflammatory signal recognised by the cell, it undergoes translocation into the cell nucleus where it activates the expression of genes involved in inflammatory processes. In red, GFAP (Glial fibrillary acidic protein) + cells; in green, phosphorylated NF-κB factor; in blue, DAPI. Green and blue nuclei show translocation.

B: Demonstration of cell proliferation. In red, Ki67 marker showing the nuclei of cells in the proliferative phase; in green, IBA1 marker highlighting microglial cells (resident macrophages of the nervous system).

One of the limitations of conventional two-dimensional cultures is that they cannot be maintained for long. Classically, primary cells organised in monolayers are rarely grown for more than a month. This makes it difficult to assess medium- and long-term effects. In addition, 2D structuring is very limited and the protective effects of barriers such as the BBB cannot be taken into account in this situation. Another limitation is that although it is possible to obtain several cell types from a 2D stem cell culture, they don't have the same structure as the organ in vivo. Certain cell types are not present and interactions between certain cells are not possible. The development of in vitro techniques, the use of synthetic extra-cellular matrices and the growing knowledge of induction systems have gradually led to the development of culture systems enabling the production of three-dimensional cell structures, similar to "in vitro micro-organisms" called organoids. These models, which are trickier to set up than conventional 2D cultures, narrow the gap between 2D cell cultures and "complete" animal models (Hess et al., 2010). In 2021, a study highlighted the major differences between 2D and 3D cultures (table 1, Habanjar et al., 2021).

Table 1. Comparison table between 2D and 3D crop models (Habanjar et al., 2021).

Features |

2D |

3D |

|---|---|---|

Interactions |

Cell - cell (co-culture) |

Cell - cell |

Cellular forms |

Flat, stretchable |

The natural structure is preserved |

Interface |

Homogeneous exposure of all |

Heterogeneous exposure: the top layer |

Cellular differentiation |

Moderately/poorly |

Differentiated |

Cell proliferation |

Proliferation rate higher |

The rate of proliferation depends on |

Sensitivity to treatments |

High |

Moderate |

Cost |

Less |

High |

2.3. Use of stem cells for 3D cultures

a. Organoids

While in vitro 2D approaches using stem cells have many advantages, the production of 3D organoids offers even more. On the one hand, they are physiologically closer to the in vivo reality: inter-cell interactions are equivalent, and on the other hand, because they can be maintained in culture over time, organoids enable longitudinal monitoring. Organoids are self-organising and self-renewing three-dimensional cellular structures that mimic organs in structure and function. Therefore, in most current studies (Lancaster and Knoblich, 2014; Rossi et al., 2018), in order to define 'organoids' it is necessary to find these self-renewing and self-organising features of multicellular structures containing multiple organ-specific cells in a similar way to that observed in vivo. Depending on the culture medium and the associated growth factors, different types of organoids can be created (Scalise et al., 2021).

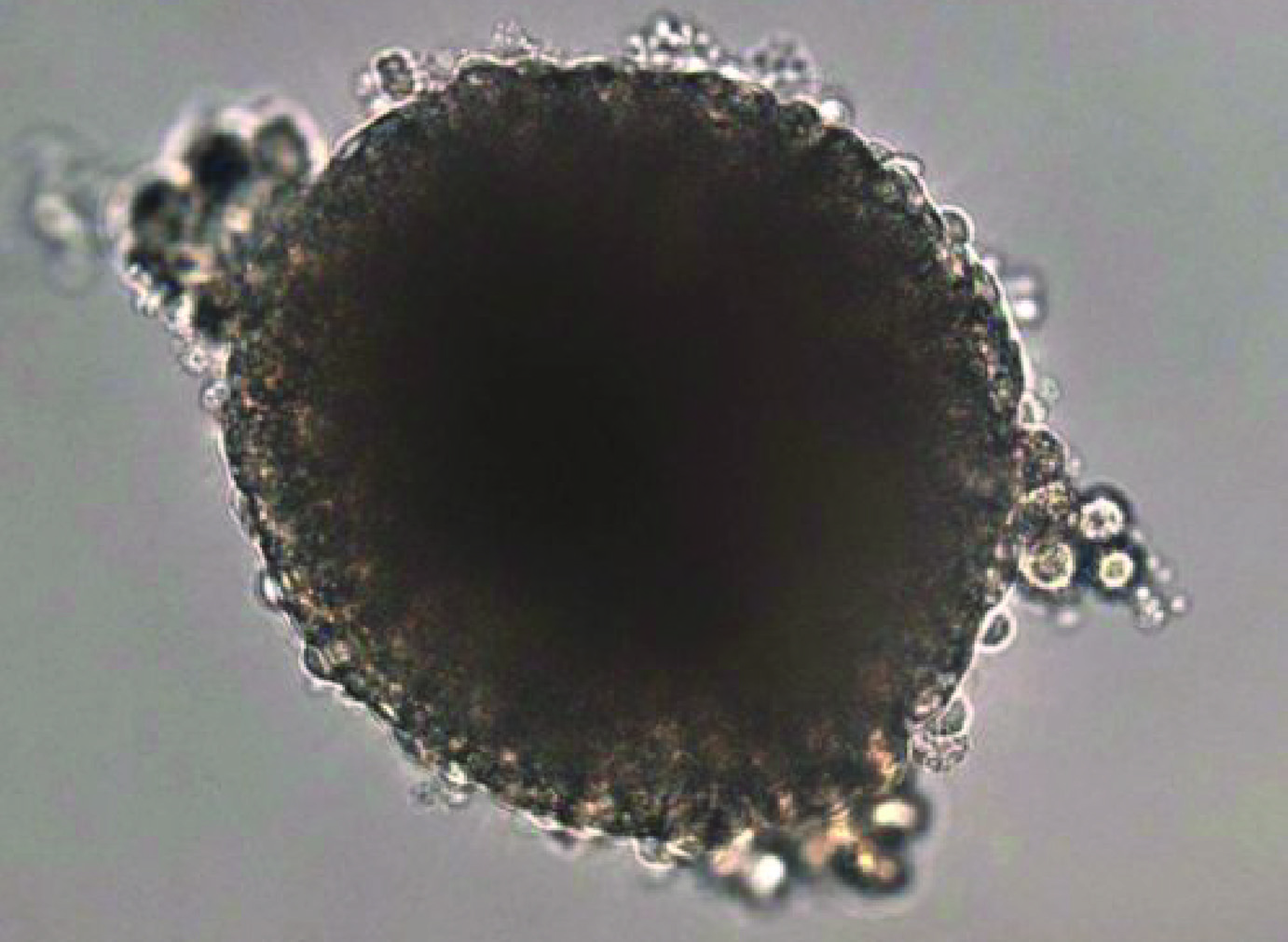

Organoids can be generated from adult stem cells (Sato et al., 2009), embryonic stem cells (Hasegawa et al., 2016), or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These iPSCs are generated by 'reprogramming' differentiated somatic cells (e.g. skin fibroblasts) to regain their pluripotency (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). Although the term 'organoid' has been used in literature for decades for any 3D structure in culture, there is now a more precise definition. In the case of NSCs, the use of neurospheres (brain organoids) makes it possible to study all the cell types of the central nervous system (CNS), such as the different subtypes of neurons, and also glial cells, namely oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Phase contrast photograph of a neurosphere, a cerebral organoid, obtained from an NSC culture. This is a three-dimensional grouping of stem cells that will lead to the differentiation of different cerebral cell types, resulting in a cerebral organoid.

Developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) induced by environmental pollutants is a risk to be considered for human health. Until now, most DNT tests have been carried out on animals. As well as being difficult to extrapolate to humans, these in vivo tests are time-consuming, expensive, and use a large number of animals. In order to study the basic processes of brain development, neurospheres are used to study cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and cell migration (Fritsche et al., 2011). This culture model can also be used to study the migration of immature neurons, the neuroblasts, which migrate during adult neurogenesis (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Detection of neuroblasts in neurospheres. Immunocytology using neurospheres deposited on a Matrigel® matrix.

The widespread and increasing implementation of organoid-based technologies in human biomedical research testifies to their enormous potential in basic, translational and applied research. Similarly, there appear to be many potential research applications for organoids derived from livestock and companion animals (Lee et al., 2021). In addition, organoids, like in vitro models, offer a great opportunity to reduce the use of laboratory animals. The development of in vitro organoid culture systems has transformed biomedical research, as they provide a reproducible cell culture system that represents a simplified version of an organ. As the majority of infectious agents enter the body or reside on mucosal surfaces, organoids derived from mucosal sites such as the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urogenital tracts have the potential to transform research into host-pathogen interactions. They enable detailed studies of early infection processes that are difficult to address using animal models.

b. Organoids and their many applications

A recent study demonstrated the feasibility of generating organoids from bovine ileum tissue, with the derived organoids expressing genes associated with intestinal epithelial cell types (Hamilton et al., 2018). In this current study, we aim to explore ways of reducing and replacing the use of animals in experiments in line with the 3Rs principle. Organoids are therefore a promising new in vitro tool for animal and veterinary research. For example, the development of sheep gastric and intestinal organoids has enabled the study of host-pathogen interactions in ruminants. The first published observations of a helminth infecting gastric and intestinal organoids in competition with the sheep parasitic nematode Teladorsagia circumcincta illustrate the usefulness of these organoids for pathogen co-culture experiments (Smith et al., 2021). Finally, the polarity of abomasal and ileal organoids can be reversed to make the apical surface directly accessible to pathogens or their products, as shown by the infection of apical organoids by the zoonotic bacterium Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Forbester et al., 2015). This in vitro culture system is both simple and reliable for the generation and maintenance of small ruminant intestinal and gastric organoids.

In addition, it has been shown that organoids can be cryopreserved (Lu et al., 2017), and cultures can be restored from cryopreserved stocks, retaining similar functionality to the original tissue. This allows long-term storage of organoid lines, reducing the number of animals needed as a tissue source (Puschmann et al., 2017). Organoid cultures can generally be maintained for very long periods (months or even more than a year), as has been demonstrated for organoids derived, for example, from the intestine, stomach, liver and pancreas, as well as for organoids derived from iPSCs (Barker et al., 2010; Buske et al., 2012; Broutier et al., 2016).

Organoid cultures can remain true to their tissue of origin and be able to recapitulate disease pathology when cultured with tissue from clinical patients (Gao et al., 2014). They are also compliant with genetic manipulation (Miyoshi and Stappenbeck, 2013), live imaging, gene expression analysis, sequencing, and epigenetic analysis, as well as other standard biological assays. Organoids, unlike cell lines, contain multiple cell types, but the tissue topology and cell-cell interactions strongly resemble key organ or tissue features in vivo (Gjorevski et al., 2014), unlike cell lines. Indeed, cell lines are generally derived from tumours and therefore easily display chromosomal aberrations and mutations (Kasai et al., 2016). These changes affect growth, metabolism, and physiology and are known to evolve during their in vitro subculturing, creating reproducibility issues (Ben-David et al., 2018). Organoids also have an advantage over tissue explants or primary cell cultures, both of which undergo senescence, cell death, and necrosis after relatively short periods of time, resulting in poor reproducibility and accuracy of biological experiments. As organoids can be derived from cells or tissues from different organisms, they can be used to test species- or individual-specific drug responses (Pasch et al., 2019). For farm animals, animal-specific organoids can therefore be used for in vitro phenotyping of parameters of interest (Clark et al., 2020).

3. Example of the study of the effects of pesticides on brain cells

In the laboratory, stem cells used as an in vitro model of toxicity were isolated from the subventricular ventricular zone (V-SVZ). These studies studies investigated the potential deleterious effects of a herbicide, ammonium glufosinate (Feat-Vetel et al., 2018), as well as an environmental toxin, β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) (Méresse et al., 2022).

3.1. Cerebral stem cells derived from the subventricular ventricular zone

The subventricular ventricular zone (V-SVZ) is located at the edge of the cerebral ventricles and is composed of multipotent neural stem cells (B1-type cells) that can differentiate into different cell types such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, ependymal cells (E-type cells), and transit amplifying neural progenitor cells (C-type cells) (Doetsch et al., 1997; Menn et al., 2006; Ortega et al., 2013). C-type cells can in turn give rise to neuroblasts (A-type cells) that migrate over a long distance into the olfactory bulb via the rostral migratory stream (Alvarez-Buylla and Lim, 2004). This particular organisation enables a neurogenic microenvironment to be maintained throughout life. In addition, the V-SVZ appears to be a potential target site for pesticides because some V-SVZ cells are in direct contact with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF fills the cerebral ventricles and can contain potentially dangerous exogenous molecules. Thus, a disruption can result in impairments of the neurogenic functions of the V-SVZ in the neurogenic functions of the V-SVZ, and potentially lead to neurodevelopmental disorders such as hydrocephalus (Jiménez et al., 2014). Disturbances within the V-SVZ, such as abnormal proliferation and differentiation, have been observed previously following exposure to pollutants (Franco et al., 2014; Paradells et al., 2015), and are suspected of playing a role in various tumorigenic cancers (Gilbertson and Rich, 2007; Zong et al., 2015).

Our recent studies carried out in the laboratory on several types of models have investigated the potential effects of pesticides on the development of the nervous system following perinatal exposure. Pesticides have always been used at low concentrations, with chosen doses below the NOAEL (Non Observed Adverse Effect Level) threshold.

3.2. Results with our in vivo model

The results obtained with our in vivo model of perinatal exposure in mice have shown that the herbicide glufosinate ammonium induces not only an alteration in sensory-motor behaviour in the post-natal period, but also a long-term behavioural alteration in animals that have become adults, without re-exposure (Laugeray et al., 2014; Herzine et al., 2016). In this in vivo model, we observed a disruption to cell proliferation and morphology in the subventricular ventricular zone (SVZ), the main neurogenic niche located in the walls of the lateral ventricles of the brain (Herzine et al., 2016). We therefore hypothesised that developmental exposure to glufosinate could lead to neurodevelopmental disorders via disruption of neurogenesis.

In addition, we used transcriptomic analysis of the brains of animals exposed during the perinatal period, to reveal a strong disruption to the expression of a set of genes potentially involved in the development of the neurogenic environment (Herzine et al., 2016). At brain level, histological analyses have shown a disruption to neuroblast migration, and molecular analyses have shown a change in the expression of genes involved in cytoskeleton homeostasis. Interestingly, when studying the cytoskeletal genes affected, it was observed that subunit 1 of the tubulin polyglutamylase complex (TPGS1) involved in the polyglutamylation mechanism was deregulated (Herzine et al., 2016). This indicates that perinatal exposure to ammonium glufosinate alters TPGS1 expression and is therefore likely to affect the cytoskeleton by disrupting polyglutamylation. Polyglutamylation (PolyE) is a post-translational modification (PTM) corresponding to the addition or removal of glutamate on the C-terminal tail regions of tubulin to form polyglutamate side chains (Edde et al., 1990; Bobinnec et al., 1999). PolyE is a rapid and reversible mechanism occurring on the tubulin of neurons and plays an important role in cell morphology, proliferation, and differentiation. It also plays a very important role in the structuring of cell cilia, for example in ependymocytes (Janke et al., 2008). These cells ensure the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid thanks to their ciliary beating. We therefore suspected a deleterious effect of ammonium glufosinate on ependymocyte cilia.

3.3. Results with our 2D in vitro model

To study the effect of ammonium glufosinate, we used a 2D NSC culture model. By using specific growth factors, it is possible to either maintain these cells in an undifferentiated state, or induce their differentiation, in particular into ependymocytes (Guirao et al., 2010; Spassky et al., 2005). This in vitro model enabled us to demonstrate the interaction of this herbicide with the cytoskeleton involved in the formation of cilia, which are characteristic of these epithelial cells found in the cerebral ventricles. In this case, we did not obtain a modification of their differentiation, but an alteration in the formation of multiciliated tufts, going as far as their disappearance (Feat-Vetel et al., 2018). Furthermore, by using a supplemented culture medium (N2 supplement), which leads to differentiation into cells typical of SVZ cell populations (i.e. neuroblasts, astrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursors), we were able to show a disturbance in cell differentiation and thus prove that exposure to this compound altered the proportions of the different cell types (Feat-Vetel et al., 2018). In another study, in which we analysed the effects of an environmental cyanotoxin, this stem cell model enabled us, among other things, to show its genotoxic and oxidative stress effects at low doses for the first time (Laugeray et al., 2018).

3.4. Example of the use of neurospheres to study the impact of environmental pollutants

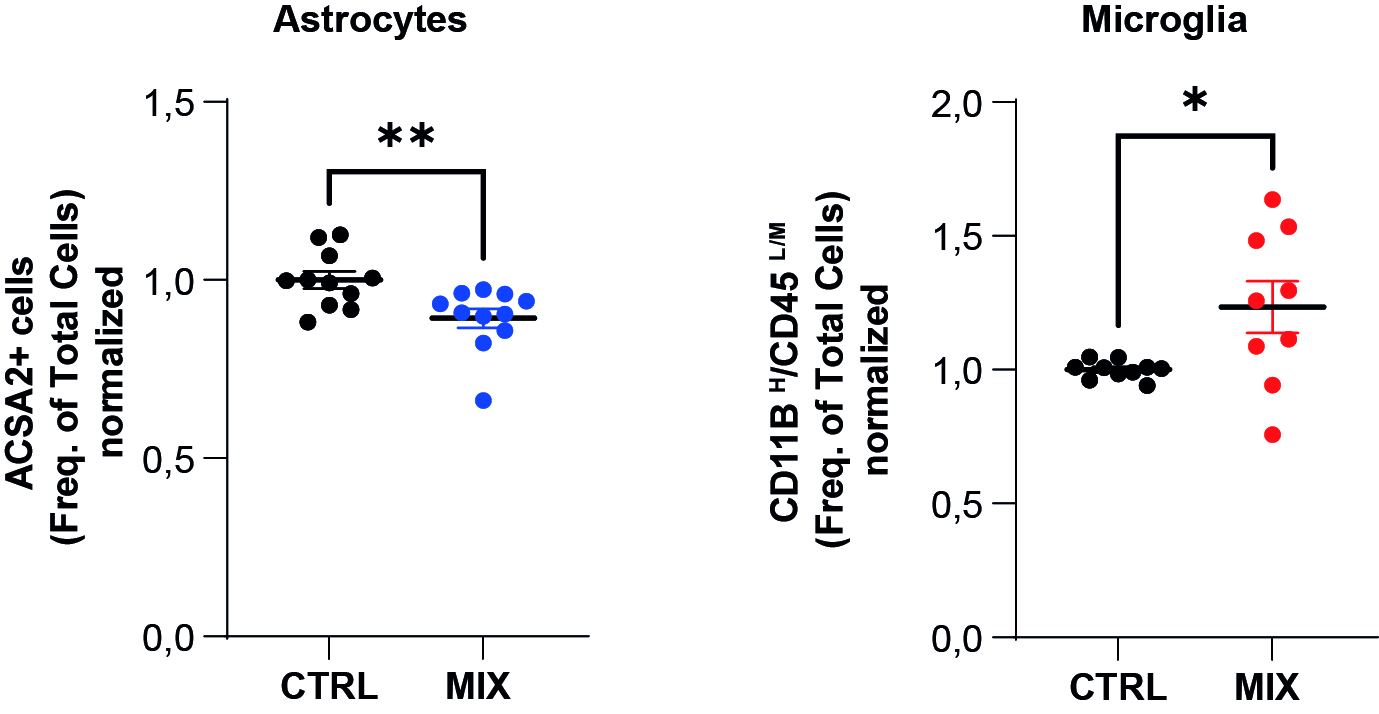

Within the neurosphere model, we can obtain all the neuronal (i.e. neurons) and glial (i.e. ependymocytes, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes) cell populations. As part of a study to analyse the effects of a mixture of environmental pollutants (called MIX in the figures), we used in vitro NSC cultures to create this neurosphere culture model. Our study focused on the induction of neurotoxic and/or neuroinflammatory processes by this MIX. Using flow cytometry studies, we were able to identify that this MIX was likely to disrupt populations of immunocompetent CNS cells, namely astrocytes and microglia. Treatment with MIX actually reduces the astrocyte population and induces an increase in the microglial cell population (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Quantification of cell population by flow cytometry.

Quantification of the astrocytic population on the left, and the microglial population (resident macrophages of the nervous system) on the right (ACSA2 cell labelling+ and CD11B /CD45highLow /Medium respectively).

This culture model allowed us to study each cell type present in brain structures. Interestingly, within neurospheres, cell maturation follows the stages normally found in the nervous system. The best example is microglial cells. During their maturation, these cells express a specific marker ("transmembrane protein 119", TMEM119). In mice, this marker is produced in these cells around day 10 after birth (Bennett et al., 2016). This marker is never expressed in 2D microglial cultures, even when co-cultured, because the cells seem to retain a juvenile phenotype. On the contrary, after some time in culture, the microglial cells present in neurospheres express TMEM119, reflecting their ability to differentiate when using this in vitro method.

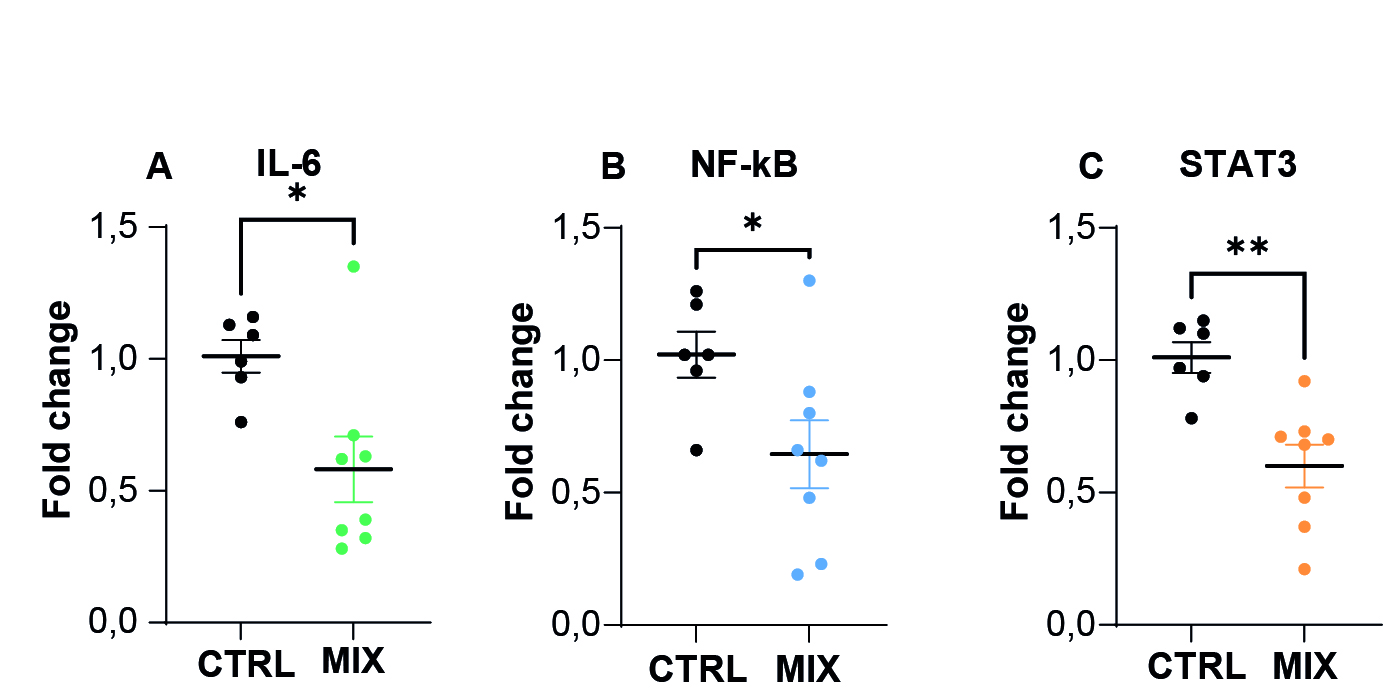

There is therefore every reason to believe that our model is well suited to tackling the neuroinflammatory problems associated with potential exposure. The neurospheres contain the microglial cells involved in this neuroinflammation, and have a maturation characteristic of the developing nervous system. Using these organoids treated with a cocktail of environmental pollutants, we were able to measure changes in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, determine the activation status of microglial cells using flow cytometry studies, and study changes in cell populations in these neurospheres. Within these models, we also measured the expression of genes involved in neuroinflammation, and found that exposure to a cocktail of pollutants reduced the expression of IL-6 and the transcript factors NF-κB and STAT3, indicating a potential modulation of the inflammatory response by these pollutants present in a mixture (Figure 7). In this way, it has become possible not only to study the neuroinflammatory reactions induced by exposure to toxic substances in vitro, but also to monitor the 'resolution' of inflammation (i.e. cellular resilience) over time, by measuring cytokine levels in the culture medium.

Figure 7. RT-qPCR measurement of gene expression of inflammation markers following exposure to a mixture of pollutants (MIX).

Worryingly, a number of bacterial and viral infections during the gestational period are at the origin of neuroinflammatory phenomena, and are associated, among others, with an increased risk of neurodegeneration. One of the limitations of cerebral organoids is that it remains difficult to achieve earlier systemic pre-exposure to another pro-inflammatory agent, as can be done in vivo (exposure during gestation to a bacterial agent, followed by exposure to pollutants after birth).

Conclusion

In human biomedical research, organoids have many potential applications as in vitro research models, including toxicology, developmental processes, congenital diseases, infectious diseases (Castellanos-Gonzalez et al., 2013), cancer (Drost and Clevers, 2018), and regenerative medicine (Nakamura and Sato, 2018). In addition, organoids are becoming better defined and can be used to obtain phenotypic information on the underlying cellular and molecular aspects.

Organoids can be of great use in farm animal and veterinary research. Their use can lead to a better understanding of animal physiology, animal nutrition and host-microbe interaction, and can contribute to the in vitro phenotyping of breeding animals. Despite this, more research is needed. There are still relatively few studies on organoids in the fields of veterinary research and animal production. To date, there are no three-dimensional in vitro models for certain species. When they do exist, most of the organoids that are set up are intestinal only.

Compared with other in vitro models, organoids reproduce a better tissue structure and function. Compared with intact organs, they are highly simplified models, which is an advantage for studies aimed at identifying specific mechanisms, but also confers clear limitations on the model. As a result, animal experiments still seem essential for preclinical screening in the drug discovery process. These requirements are confronted with the need for ethical considerations, and the problem of differences between species. This is why the use of organoid models based on cells of human origin is being actively pursued.

These 3D models cannot be applied to all studies, and do not reflect the interactions between organs. As a result, it remains difficult to accurately predict the efficacy of drugs and their potential toxicity. One avenue that could be explored is the body-on-chip technique. This is a network of miniature in vitro organs that work together to mimic body systems. These models can use human cells, giving them greater precision than traditional animal models while increasing the possibility of personalised medicine, where cells could be derived from a patient’s own stem cells. While the use of organoids is a good alternative to the use of in vivo models, these in vitro systems on chips could bridge the gap between animal studies and clinical trials for the pharmaceutical industry.

Acknowledgements

This article was first translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and the authors thank Mrs Fourcin Deki for English language editing.

References

- Abeysiriwardena N.M., Gascoigne S.J.L, Anandappa A., 2018. Algal bloom expansion increases cyanotoxin risk in food. Yale J. Biol. Med., 91, 129-142. PMID: 29955218; PMCID: PMC6020737. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6020737/

- Ahmadpour D., Mhaouty-Kodja S., Grange-Messent V., 2022. Les phtalates - Un facteur de risque pour la fonction cérébro-vasculaire chez la souris mâle. Med. Sci., Paris, France. 38, 141-144. French. doi:10.1051/medsci/2021256

- Alvarez-Buylla A., Lim D.A., 2004. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron, 41, 683-686. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00111-4

- Andersen S.L., 2003. Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 27, 3-18. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(03)00005-8

- Ankley G.T., Bennett R.S., Erickson R.J., Hoff D.J., Hornung M.W., Johnson R.D., Mount D.R., Nichols J.W., Russom C.L., Schmieder P.K., Serrrano J.A., Tietge J.E., Villeneuve D.L., 2010. Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 29,730-741. doi:10.1002/etc.34

- Barker N., Huch M., Kujala P., van de Wetering M., Snippert H.J., van Es J.H., Sato T., Stange D.E., Begthel H., van den Born M., Danenberg E., van den Brink S., Korving J., Abo A., Peters P.J., Wright N., Poulsom R., Clevers H., 2010. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 6, 25-36. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013

- Ben-David U., Siranosian B., Ha G., Tang H., Oren Y., Hinohara K., Strathdee C.A., Dempster J., Lyons N.J., Burns R., Nag A., Kugener G., Cimini B., Tsvetkov P., Maruvka Y.E., O’Rourke R., Garrity A., Tubelli A.A., Bandopadhayay P., Tsherniak A., Vazquez F., Wong B., Birger C., Ghandi M., Thorner A.R., Bittker J.A., Meyerson M., Getz G., Beroukhim R., Golub T.R., 2018. Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature, 560, 325-330. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0409-3

- Bennett M.L., Bennett F.C., Liddelow S.A, Ajami B., Zamanian J.L., Fernhoff N.B., Mulinyawe S.B., Bohlen C.J., Adil A., Tucker A., Weissman I.L., Chang E.F., Li G., Grant G.A., Hayden Gephart M.G., Barres B.A., 2016. New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E1738-E1746. PMID: 26884166; PMCID: PMC4812770. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525528113

- Bilbo S.D., Schwarz J.M., 2009. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: a critical role for the immune system. Front. Behav. Neurosci., 24, 3-14. PMID: 19738918; PMCID: PMC2737431. doi:10.3389/neuro.08.014.2009

- Bobinnec Y., Marcaillou C., Debec A., 1999. Microtubule polyglutamylation in Drosophila melanogaster brain and testis. Eur. J. Cell. Biol., 78, 671-674. doi:10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80053-3

- Bolton J.L, Bilbo S.D., 2014. Developmental programming of brain and behavior by perinatal diet: focus on inflammatory mechanisms. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci.,16, 307-320. PMID: 25364282; PMCID: PMC4214174. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.3/jbolton

- Broutier L., Andersson-Rolf A., Hindley C.J., Boj S.F., Clevers H., Koo B.K., Huch M., 2016. Culture and establishment of self-renewing human and mouse adult liver and pancreas 3D organoids and their genetic manipulation. Nat. Protoc., 11, 1724-1743. Epub 2016 Aug 25. PMID: 27560176. doi:10.1038/nprot.2016.097

- Buske P., Przybilla J., Loeffler M., Sachs N., Sato T., Clevers H., Galle J., 2012. On the biomechanics of stem cell niche formation in the gut--modelling growing organoids. FEBS J. , 279, 3475-3487. Epub 2012 Jun 18. PMID: 22632461. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08646.x

- Castellanos-Gonzalez A., Cabada M.M., Nichols J., Gomez G., White Jr A.C., 2013. Human primary intestinal epithelial cells as an improved in vitro model for Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect. Immun., 81,1996-2001. doi:10.1128/IAI.01131-12

- Chen Z., Jang S., Kaihatu J.M., Zhou Y.H., Wright F.A., Chiu W.A., Rusyn I., 2021. Potential human health hazard of post-hurricane harvey sediments in galveston bay and houston ship channel: a case study of using in vitro bioactivity data to inform risk management decisions. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health., 18, 13378. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413378

- Clark E.L., Archibald A.L., Daetwyler H.D., Groenen MA.M., Harrison P.W., Houston R.D., Kühn C., Lien S., Macqueen D.J., Reecy J.M., Robledo D., Watson M., Tuggle C.K., Giuffra E., 2020. From FAANG to fork: application of highly annotated genomes to improve farmed animal production. Genome Biol., 21, 285. doi:10.1186/s13059-020-02197-8

- Costa E.C., Moreira A.F, de Melo-Diogo D., Gaspar V.M., Carvalho M.P., Correia I.J., 2016. 3D tumor spheroids: an overview on the tools and techniques used for their analysis. Biotechnol Adv. 34, 1427-1441. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.

- Coumoul X., Andujar P., Baeza-Squiban A., Barouki R., Bodin L., 2023. Toxicologie 2ème édition. Éditions Dunod. ISBN : 978-2-10-076173-9. https://www.dunod.com/sciences-techniques/toxicologie-1

- D'Almeida M., Sire O., Lardjane S., Duval H., 2020. Development of a new approach using mathematical modeling to predict cocktail effects of micropollutants of diverse origins. Environ. Res., 188, 109897. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109897

- Danoy M., Jellali R., Tauran Y., Bruce J., Leduc M., Gilard F., Gakière B., Scheidecker B., Kido T., Miyajima A., Soncin F., Sakai Y., Leclerc E., 2021. Characterization of the proteome and metabolome of human liver sinusoidal endothelial-like cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. Differentiation, 120, 28-35. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2021.06.001

- Dietert R.R., 2012. Misregulated inflammation as an outcome of early-life exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Rev. Environ. Health, 27, 117-131. doi:10.1515/reveh-2012-0020

- Doetsch F., Garcı́a-Verdugo J.M., Alvarez-Buylla A., 1997. Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain. J. Neurosci., 17, 5046-5061. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05046.1997

- Dridi I., Leroy D., Guignard C., Goerges S., Torsten B., Landoulsi A., Thomé J.P., Eppe G., Soulimani R., Bouayed J., 2014. Dietary early-life exposure to contaminated eels does not impair spatial cognitive performances in adult offspring mice as assessed in the Y-maze and the Morris water maze. Nutr Res., 34, 1075-1084. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2014.06.011

- Dridi I., Soulimani R., Bouayed J., 2021. Chronic depression-like phenotype in male offspring mice following perinatal exposure to naturally contaminated eels with a mixture of organic and inorganic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int., 28, 156-165. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-08799-w

- Drost J., Clevers H., 2018. Organoids in cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer., 18, 407-418. doi:10.1038/s41568-018-0007-6

- Fall C., 2009. Maternal nutrition: effects on health in the next generation. Indian J. Med. Res., 130, 593-599. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20090113/

- Feat-Vetel J., Larrigaldie V., Meyer-Dilhet G., Herzine A., Mougin C., Laugeray A., Gefflaut T., Richard O., Quesniaux V., Montécot-Dubourg C., Mortaud S., 2018. Multiple effects of the herbicide glufosinate-ammonium and its main metabolite on neural stem cells from the subventricular zone of newborn mice Neuro Toxicology., 69, 152-163 doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2018.10.001

- Forbester J.L, Goulding D., Vallier L., Hannan N., Hale C., Pickard D., Mukhopadhyay S., Dougan G., 2015. Interaction of salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium with intestinal organoids derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Infect. Immun., 83, 2926-2934. doi:10.1128/IAI.00161-15

- Franco I., Valdez-Tapia M., Sanchez-Serrano S.L., Cruz S.L., Lamas M., 2014. Chronic toluene exposure induces cell proliferation in the mice SVZ but not migration through the RMS. Neurosci. Lett., 575, 101-106. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.043

- Fritsche E., Gassmann K., Schreiber T., 2011. Neurospheres as a model for developmental neurotoxicity testing. Methods Mol. Biol., 758, 99-114. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-170-3_7

- Gao D., Vela I., Sboner A., Iaquinta P.J., Karthaus W.R., Gopalan A., Dowling C., Wanjala J.N., Undvall E.A., Arora V.K., Wongvipat J., Kossai M., Ramazanoglu S., Barboza L.P., Di W., Cao Z., Zhang Q.F., Sirota I., Ran L., MacDonald T.Y., Beltran H., Mosquera J.M., Touijer K.A., Scardino P.T., Laudone V.P., Curtis K.R., Rathkopf D.E., Morris M.J., Danila D.C., Slovin S.F., Solomon S.B., Eastham J.A., Chi P., Carver B., Rubin M.A., Scher H.I., Clevers H., Sawyers C.L., Chen Y., 2014. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cell., 159, 176-187. https://doi.org10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.016

- Gilbertson R.J., Rich J.N., 2007. Making a tumour’s bed: glioblastoma stem cells and the vascular niche. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 7, 733-736. doi:10.1038/nrc2246

- Gjorevski N., Ranga A., Lutolf M.P., 2014. Bioengineering approaches to guide stem cell-based organogenesis. Development, 141, 1794-1804. doi:10.1242/dev.101048

- Guirao B., Meunier A., Mortaud S., Aguilar A., Corsi J.M., Strehl L., Hirota Y., Desoeuvre A., Boutin C., Han Y.G., Mirzadeh Z., Cremer H., Montcouquiol M., Sawamoto K., Spassky N., 2010. Coupling between hydrodynamic forces and planar cell polarity orients mammalian motile cilia. Nat. Cell. Biol., 12, 341-350. doi:10.1038/ncb2040

- Habanjar O., Diab-Assaf M., Caldefie-Chezet F., Delort L., 2021. 3D Cell Culture Systems: Tumor application, advantages, and disadvantages. Int. J. Mol. Sci.,22, 12200. doi:10.3390/ijms222212200

- Hagberg H., MallardC., Ferriero, D.M., Vannucci S.J., Levison S.W., Vexler Z.S., Gressens P., 2015. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol., 11, 192-208. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2015.13

- Hale M.W., Spencer S.J., Conti B., Jasoni C.L., Kent S., Radler M.E., Reyes T.M., Sominsky L., 2014. Diet, behavior and immunity across the lifespan. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 58, 46-62. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.009

- Hamilton C.A., Young R., Jayaraman S., Sehgal A., Paxton E., Thomson S., Katzer F., Hope J., Innes E., Morrison L.J., Mabbott N.A., 2018. Development of in vitro enteroids derived from bovine small intestinal crypts. Vet. Res., 49, 54. doi:10.1186/s13567-018-0547-5

- Hasegawa Y., Takata N., Okuda S., Kawada M., Eiraku M., Sasai Y., 2016. Emergence of dorsal-ventral polarity in ESC-derived retinal tissue. Development. 143, 3895-3906. doi:10.1242/dev.134601

- Herzine A., Laugeray A., Feat J., Menuet A., Quesniaux V., Richard O., Pichon J., Montécot-Dubourg C., Perche O., Mortaud S., 2016. Perinatal exposure to glufosinate ammonium herbicide impairs neurogenesis and neuroblast migration through cytoskeleton destabilization. Front Cell Neurosci., 10, 191. doi:10.3389/fncel.2016.00191

- Hess M.W., Pfaller K., Ebner H.L, Beer B., Hekl D., Seppi T., 2010. 3D versus 2D cell culture implications for electron microscopy. Methods Cell Biol., 96, 649-670. doi:10.1016/S0091-679X(10)96027-5

- Ingber S.Z., Pohl H.R., 2016. Windows of sensitivity to toxic chemicals in the motor effects development. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 74, 93-10. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.11.018

- Janke C., Rogowski K., van Dijk J., 2008. Polyglutamylation: a fine-regulator of protein function? 'Protein Modifications: beyond the usual suspects' review series. EMBO Rep., 9, 636-641. doi:10.1038/embor.2008

- Jean-Quartier C., Jeanquartier F., Jurisica I. Holzinger A., 2018. In silico cancer research towards 3R. BMC Cancer, 18, 408. doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4302-0

- Jervis M., Huaman O., Cahuascanco B., Bahamonde J., Cortez J., Arias J.I., Torres C.G., Peralta O.A., 2019. Comparative analysis of in vitro proliferative, migratory and pro-angiogenic potentials of bovine fetal mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow and adipose tissue. Vet. Res. Commun., 43, 165-178. doi:10.1007/s11259-019-09757-9

- Jiménez A.J., Dominguez-Pinos M.D., Guerra M.M., Fernandez-Llebrez P., Pèrez- Figares J.M., 2014. Structure and function of the ependymal barrier and diseases associated with ependyma disruption. Tissue Barriers, 2, doi:10.4161/tisb.28426

- Johnston J.J., Savarie P.J., Primus T.M., Eisemann J.D., Hurley J.C., Kohler D.J., 2002. Risk assessment of an acetaminophen baiting program for chemical control of brown tree snakes on Guam: evaluation of baits, snake residues, and potential primary and secondary hazards. Environ. Sci. Technol., 36, 3827-3833. doi:10.1021/es015873n

- Karahahil B., 2016. Overview of systems biology and omics technologies. Curr. Med. Chem., 23, 4221-4230. doi:10.2174/0929867323666160926150617

- Karkaba A., Soualeh N., Soulimani R., Bouayed J., 2017. Perinatal effects of exposure to PCBs on social preferences in young adult and middle-aged offspring mice. Horm. Behav., 96, 137-146. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.09.002

- Kasai F., Hirayama N., Ozawa M., Iemura M., Kohara A., 2016. Changes of heterogeneous cell populations in the Ishikawa cell line during long-term culture: Proposal for an in vitro clonal evolution model of tumor cells. Genomics. 107, 259-66. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2016.04.003

- La Rocca C., Mantovani A., 2006. From environment to food: the case of PCB. Ann. Ist. Super Sanita. 42, 410-416. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17361063/

- Lancaster M.A., Knoblich J.A., 2014. Organogenesis in a dish: modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science, 345, 1247125. doi:10.1126/science.1247125

- Laugeray A., Herzine A., Perche O., Hébert B., Aguillon-Naury M., Richard O., Menuet A., Mazaud-Guittot S., Lesné L., Briault S., Jegou B., Pichon J., Montécot-Dubourg C., Mortaud S., 2014. Pre- and postnatal exposure to low dose glufosinate ammonium induces autism-like phenotypes in mice. Front Behav. Neurosci., 8, 390. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00390

- Laugeray A., Herzine A., Perche O., Richard O., Montecot-Dubourg C., Menuet A., Mazaud-Guittot S., Lesné L., Jegou B., Mortaud S., 2017. In utero and lactational exposure to low-doses of the pyrethroid insecticide cypermethrin leads to neurodevelopmental defects in male mice-An ethological and transcriptomic study. PLoS One. 11, e0184475. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184475

- Laugeray A., Oummadi A., Jourdain C., Feat J., Meyer-Dilhet G., Menuet A., Plé K., Gay M., Routier S., Mortaud S., Guillemin G.J., 2018. Perinatal exposure to the cyanotoxin β-n-méthylamino-l-alanine (bmaa) results in long-lasting behavioral changes in offspring-potential involvement of dna damage and oxidative stress. Neurotox. Res., 33, 87-112. doi:10.1007/s12640-017-9802-1

- Lauritzen L., Hansen H.S., Jørgensen M.H., Michaelsen K.F., 2001. The essentiality of long chain n-3 fatty acids in relation to development and function of the brain and retina. Prog Lipid Res., 40, 1-94. doi:10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00017-5

- Lee B.R., Yang H., Lee S.I., Haq I., Ock S.A., Wi H., Lee H.C., Lee P., Yoo J.G., 2021. Robust three-dimensional (3d) expansion of bovine intestinal organoids: an in vitro model as a potential alternative to an in vivo system. Animals, 16, 2115. doi:10.3390/ani11072115

- Li L.X., Chen L., Meng X.Z., Chen B.H., Chen S.Q., Zhao Y., Zhao L.F., Liang Y., Zhang Y.H., 2013. Exposure levels of environmental endocrine disruptors in mother-newborn pairs in China and their placental transfer characteristics. PLoS One 8, e62526. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062526

- Lu Y.C., Fu D.J, An D., Chiu A., Schwartz R., Nikitin A.Y., Ma M., 2017. Scalable production and cryostorage of organoids using core-shell decoupled hydrogel capsules. Adv. Biosys., 1 1700165. doi:10.1002/adbi.201700165

- Menn B., Garcia-Verdugo J.M., Yaschine C., Gonzalez-Perez O., Rowitch D., Alvarez-Buylla A., 2006. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J. Neurosci., 26, 7907-7918. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006.

- Méresse S., Larrigaldie V., Oummadi A., de Concini V., Morisset-Lopez S., Reverchon F., Menuet A., Montécot-Dubourg C., Mortaud S., 2022. β-N-Methyl-Amino-L-Alanine cyanotoxin promotes modification of undifferentiated cells population and disrupts the inflammatory status in primary cultures of neural stem cells. Toxicology, 27, 482, 153358. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2022.153358

- Miyoshi H., Stappenbeck T.S., 2013. In vitro expansion and genetic modification of gastrointestinal stem cells in spheroid culture. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2471-2482. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.153

- Nakamura T., Sato T., 2018. Advancing intestinal organoid technology toward regenerative medicine. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 5, 51-60. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.10.006

- Ortega F., Gascón S., Masserdotti G., Deshpande A., Simon C., Fischer J., Dimou L., Chichung Lie D., Schroeder T., Berninger B., 2013. Oligodendrogliogenic and neurogenic adult subependymal zone neural stem cells constitute distinct lineages and exhibit differential rresponsiveness to Wnt signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 602-613. doi:10.1038/ncb2736

- Paradells S., Rocamonde B., Llinares C., Herranz-Pérez V., Jimenez M., Garcia- Verdugo J.M., Zipancic I., Soria J.M., Garcia-Esparza M., 2015. Neurotoxic effects of ochratoxin a on the subventricular zone of adult mouse brain. J. Appl. Toxicol. 35, 737-751. doi:10.1002/jat.3061

- Pasch C.A., Favreau P.F., Yueh A.E., Babiarz C.P., Gillette A.A., Sharick J.T., Karim M.R., Nickel K.P., DeZeeuw A.K., Sprackling C.M., Emmerich P.B., DeStefanis R.A., Pitera R.T., Payne S.N., Korkos D.P., Clipson L., Walsh C.M., Miller D., Carchman E.H., Burkard M.E., Lemmon K.K., Matkowskyj K.A., Newton M.A., Ong I.M., Bassetti M.F., Kimple R.J., Skala M.C., Deming D.A., 2019. Patient-derived cancer organoid cultures to predict sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiation. Clin. Cancer Res., 25, 5376-5387. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3590

- Pieters V.M., Co I.L., Wu N., Mc Guigan A.P., 2021. Applications of omics technologies for three-dimensional in vitro disease models. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods., 27, 183-199. doi:10.1089/ten.tec.2020.0300

- Puschmann E., Selden C., Butler S., Fuller B., 2017. Liquidus Tracking: Large scale preservation of encapsulated 3-D cell cultures using a vitrification machine. Cryobiology, 76, 65-73. doi:10.1016/j.cryobiol.2017.04.006

- Roegge C.S, Schantz S.L., 2006. Motor function following developmental exposure to PCBS and/or MEHG. Neurotoxicol. Teratol., 28, 260-277. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2005.12.009

- Rossi G., Manfrin A., Lutolf M.P., 2018. Progress and potential in organoid research. Nat. Rev. Genet., 19, 671-687. doi:10.1038/s41576-018-0051-9

- Sato T., Vries R.G., Snippert H.J., van de Wetering M., Barker N., Stange D.E., van Es J.H., Abo A., Kujala P., Peters P.J., Clevers H., 2009. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature, 459, 262. doi:10.1038/nature07935

- Scalise M., Marino F., Salerno L., Cianflone E., Molinaro C., Salerno N., De Angelis A., Viglietto G., Urbanek K., Torella D., 2021. From spheroids to organoids: the next generation of model systems of human cardiac regeneration in a dish. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22, 13180. doi:10.3390/ijms222413180

- Smith D., Price D.R.G., Burrells A., Faber M.N., Hildersley K.A., Chintoan-Uta C., Chapuis A.F., Stevens M., Stevenson K., Burgess S.T.G., Innes E.A., Nisbet A.J., McNeilly T.N., 2021. The development of ovine gastric and intestinal organoids for studying ruminant host-pathogen interactions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol., 11, 733811. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.733811

- Spassky N., Merkle F.T., Flames N., Tramontin A.D., García-Verdugo J.M., Alvarez-Buylla A., 2005. Adult ependymal cells are postmitotic and are derived from radial glial cells during embryogenesis. J. Neurosci., 25, 10-18. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1108-04.2005

- Spencer S.J., 2013. Perinatal nutrition programs neuroimmune function long-term: mechanisms and implications. Front Neurosci 7, 144. doi:10.3389/fnins.2013.00144

- Takahashi K., Yamanaka S., 2006. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell, 126, 663-676. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024

- Tauk B.S., Foster J.D., 2016. Treatment of ibuprofen toxicity with serial charcoal hemoperfusion and hemodialysis in a dog. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care (San Antonio). 26, 787-792. doi:10.1111/vec.12544

- Vaudin P., Augé C., Just N., Mhaouty-Kodja S., Mortaud S., Pillon D., 2022. When pharmaceutical drugs become environmental pollutants: Potential neural effects and underlying mechanisms. Environ. Res., 205, 112495. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112495

- Yamada K.M, Cukierman E., 2007. Modeling tissue morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell, 130, 601-610. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.006

- Zhao X., Wan W., Li B., Zhang X., Zhang M., Wu Z., Yang H., 2021. Isolation and in vitro expansion of porcine spermatogonial stem cells. Reprod. Domest. Anim., 57, 210-220. doi:10.1111/rda.14043

- Zong H., Parada L.F., Baker S., 2015. Cell of origin for malignant gliomas and its implication in therapeutic development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol., 17, a020610. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4448618/

- MORTAUD S., MÉRESSE S., LARRIGALDIE V., 2023. Intérêts des cultures in vitro de cellules souches et d’organoïdes dans le cadre d’études toxicologiques. In : Cellules souches et Organoïdes : réalités et perspectives. Taragnat C., Pain B. (Eds). Dossier, INRAE Prod. Anim., 36, 7684.

Abstract

The toxicity of our environment and its impact on health are of increasing concern to the public. Some pollutants present in the environment can affect the whole environment and the trophic chains. In some cases, they can affect wild animals, domestic animals, and even be transferred to the human species. A poisoning corresponds to an "introduction or bio-accumulation of a toxic substance in the body". The effect of these toxic substances is therefore important to assess to anticipate its consequences on organisms. Depending on the model used, these evaluations may contain important biases. Indeed, the metabolism is different from one organism to another, and therefore the ability to manage a toxin from the environment, bio-accumulate or eliminate it, is specific to the species. The toxicity for the animal assimilating them and the availability of these substances for human consumption are therefore very variable. This problem is found in another toxicological context, that of medicinal drugs. The toxicological study should therefore be specific to the target species, including the human species. In fact, there is a significant difference between the results obtained during the pre-clinical phases and those obtained during clinical trials. In addition, the use of animal models is subject to regulations within the European Union, which are particularly concerned with limiting the use of animals for scientific purposes whenever possible. In these contexts, the importance of in vitro methods that have been developed over the last few decades thanks to the advancement of fundamental knowledge on stem cells and the technical advances that have been associated with them is clear. These methods allow the production of 3-dimensional cultures mimicking the real structures of organisms, hence the name organoids. These tools are becoming key elements in toxicological approaches, whether related to toxic exposure problems or to human and veterinary preclinical studies.

Attachments

No supporting information for this article##plugins.generic.statArticle.title##

Views: 3841

Views: 3841

Downloads

PDF: 78

PDF: 78

XML: 55

XML: 55