Selection of hens on laying eggs in cage-free system (Full text available in English)

Header

To provide animals with living conditions that meet the needs of the species, cage rearing of laying hens in Europe is now gradually being replaced by cage-free systems. In these farms, hens live in groups in a large area with or without access to the outside. Their laying behaviour can be expressed more freely, and selection must evolve to consider these new living conditions.

Introduction

Genetic improvement of laying hens is carried out in pyramid selection programmes. At the selection level, purebred animals are usually reared in individual cages, for all or part of their career, to allow monitoring of their individual performance. The selection criteria (Box 1) classically recorded are related to the animal's body weight, production (number of eggs laid), and egg qualities (egg weight and shape, eggshell strength and colour, white quality, and proportion of yolk; Beaumont et al., 2010). The best individuals, i.e., those with the best genetic values (Box 1) for a weighted combination of these criteria (index), are selected as future breeders. The offspring crossed between different lines are then disseminated on a large scale by the multiplication level, allowing the production level to benefit from genetic improvement by crossing pure lines (Coudurier, 2011).

Box 1. Glossary.

- Phenotypic trait: a descriptive feature of individuals in a population.

- Genetic correlation: correlation between additive genetic values estimated for two given traits.

- Selection criterion: a trait that can be measured on candidates for selection and/or their relatives and allows the ranking of candidate breeders according to their estimated additive genetic value.

- GWAS: Genome-Wide Association Study, which consists of analysing the correlation between genetic variations and a phenotypic trait.

- Heritability: the proportion of phenotypic variance of genetic origin for a given trait and population.

- QTL: Quantitative Trait Locus, is a chromosomal region governing part of the genetic variability of a quantitative trait.

- Additive genetic value: sum of the average effects of the alleles carried by an individual on a given trait. On average, half of this value is transmitted from parent to offspring.

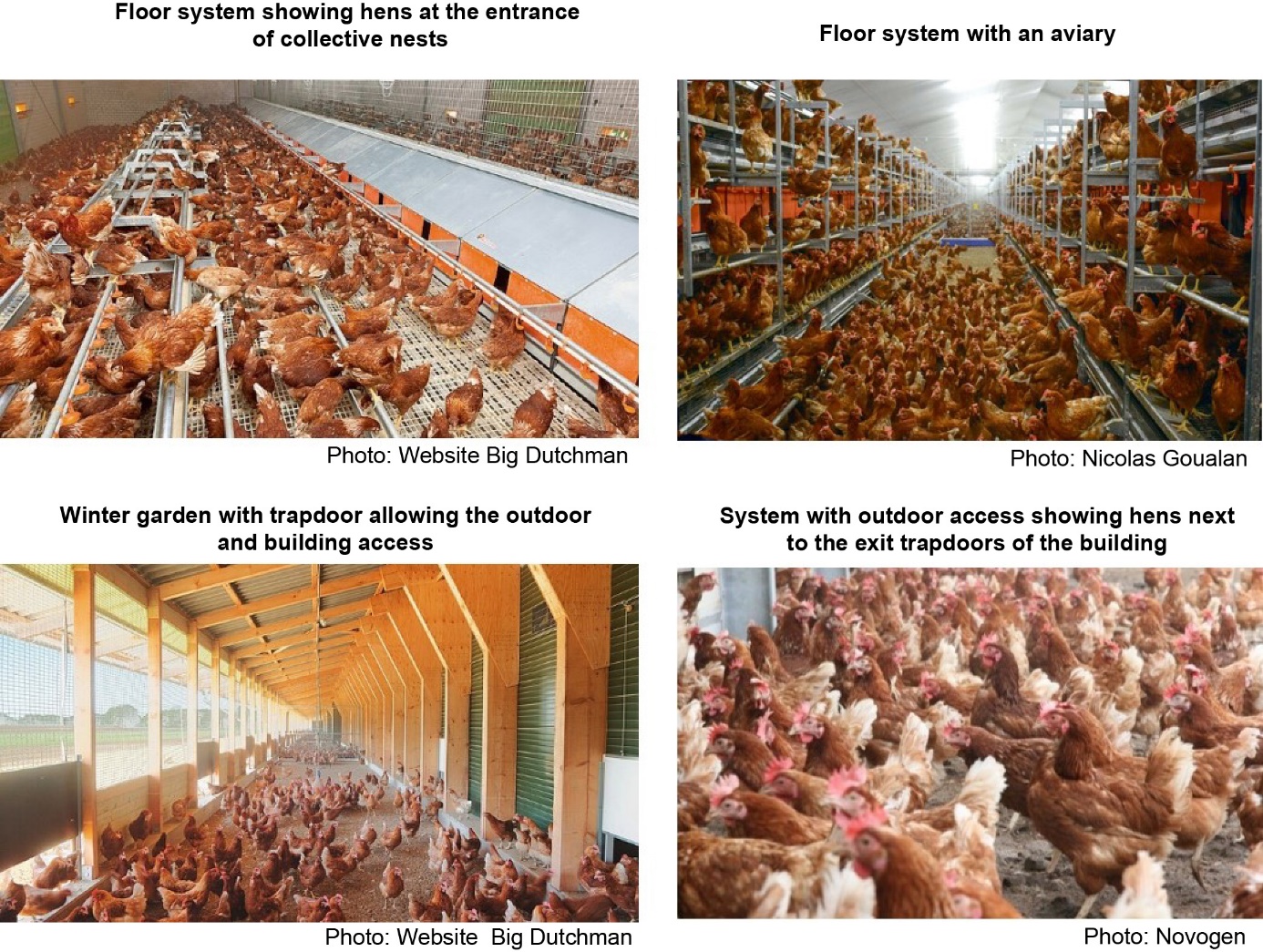

In Europe, laying hens were mainly kept in collective cages at the production level. Since 2012, these cages have been called ‘enriched cages’ because they are equipped with nests, perches, and a scratching area. In recent years, a wide range of cage-free systems have also been developed to provide animals with living conditions that meet their needs. In these systems, hens move freely in a building with or without an aviary (several levels in the building; figure 1). Adjacent to the building, there is sometimes a covered and screened exercise area (winter garden; figure 1) that allows the hens to have access to natural light and outdoor weather conditions while being protected from the elements. Some buildings have outdoor access; these are called 'free range,' 'Label Rouge free range,' and 'organic free range' systems (figure 1). Systems without outdoor access are called floor systems (figure 1). Whether the hens have access to a winter garden or the outside, natural light is often supplemented by artificial light, especially when days are short. European legislation requires that the lighting programme should follow a 24-hour rhythm, with a continuous dark period of at least 8 hours, and a light intensity that allows hens to see and be seen clearly (Directive, 1999/74/EC).

In 2019, cage-free systems accounted for 52% of commercial laying hens reared in the European Union (European Commission, 2021), compared to 30% in 2009 and 8% in 1996 (ITAVI, 2019). For hens reared in cage-free systems, 36% had outdoor access in 2019 and 64% were reared on the floor (European Commission, 2021). Currently, there is no specific breeding programme for cage-free systems; hens reared in cage-free systems are derived from the same pure lines as hens reared in cages. Therefore, cage-free system rearing is based on selection indices established on animals reared in conventional systems.

In contrast to cage rearing, hens reared in cage-free systems are housed in a large group, must lay eggs in nests (figure 1), and sometimes have outdoor access. Electronic nests have been developed to measure new egg-laying traits in these environments (Box 1), related to the pre-laying behaviour, the nesting behaviour, and the laying rate. These traits now appear in the selection objectives of pure lines. The objective of this review is to present the current state of knowledge on egg-laying traits in cage-free systems, focusing mainly on the two most widely reared breeds of laying hens in the world: Rhode Island (RI; brown eggs) and White Leghorn (WL; white eggs).

1. Egg production

Egg production, defined as the number of eggs laid in a given period, or laying rate (number of eggs laid divided by the number of days in the period) is the major criterion considered in laying hen selection schemes. While egg production is influenced by the environment, mainly the photoperiod (Sauveur, 1996; England and Ruhnke, 2020), it is also dependent on a genetic component. Thus, the existence of genetic variability in egg production has contributed to the current level of production in commercial hens capable of laying more than 300 eggs per year.

After intensive selection on sexual maturity and egg production up to 55 weeks of age, breeders are now also interested in the persistency in lay, i.e., the ability of hens to have a longer laying career (Bain et al., 2016). Currently, laying hens are reared to about 72 weeks of age. Extending their laying career to 100 weeks, with a total production of almost 500 eggs per hen, would reduce the number of hens. In the UK, for example, a 100-week laying career would reduce the number of laying hens in the country by 2.5 million (Bain et al., 2016). In addition, a longer laying career would reduce the amount of feed and therefore the negative environmental effects, particularly by reducing the amount of nitrates produced for the same level of production (Bain et al., 2016). Thus, egg production of hens older than one year is often included in the selection objective of laying hen lines (persistency in lay and stability of egg qualities, such as egg weight and shape and eggshell strength and colour).

Measured in individual cages, the number of eggs laid from the age at the first egg to 90 weeks is moderately heritable, with heritability estimates (Box 1) of 0.26 and 0.34 for RI and WL, respectively. (Wolc et al., 2019). Many chromosomal regions (QTLs; Box 1) are involved in the genetic background of egg production. Twenty-one studies have detected 95 QTLs influencing the number of eggs laid and/or laying rate (Romé and Le Roy, 2016). In particular, the genes coding for three proteins involved in folliculogenesis – prolactin (chromosome 2), the follicle stimulating hormone receptor (chromosome 3), and the gonadotropin receptor (chromosome 22) – have been identified as influencing the number of laid eggs (Romé and Le Roy, 2016). Knowledge of the genetic background of egg production, acquired in cage systems, needs to be revisited in the context of less standardised cage-free systems.

1.1. Laying in nests

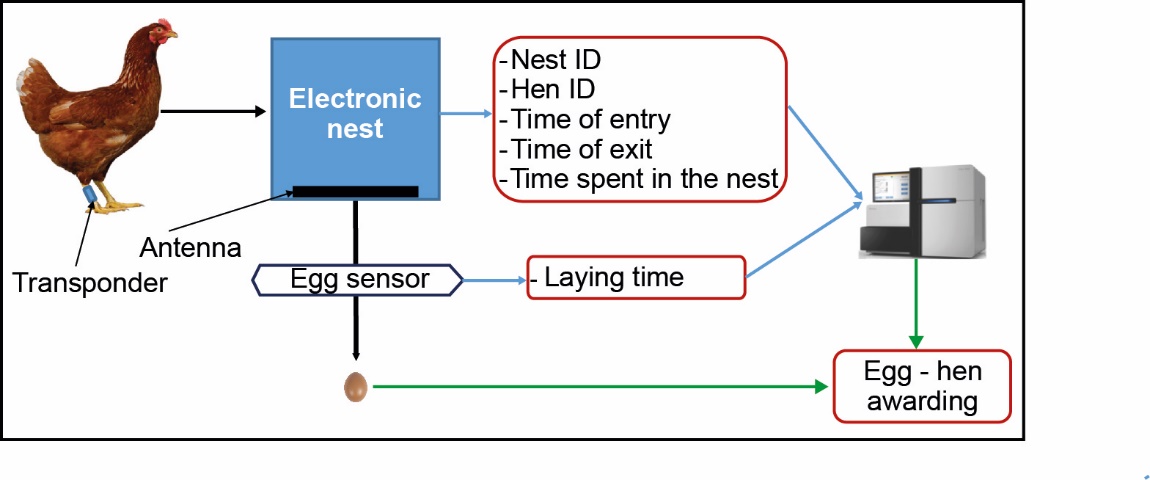

Egg production in nests, measured as the number of eggs laid in nests over a period or as the laying rate in nests (number of eggs laid in nests divided by the number of days in the period) is the proportion of egg production that is easily collected and valued by the farmer. The rapid increase in the number of laying hens kept in groups with access to collective nests has raised many questions about the ability of the animals to use the nests. In response, individual electronic nests using radio frequency identification (RFID) technology have been developed (Burel et al., 2002; Marx et al., 2002; Thurner et al., 2006). These nests are equipped with an antenna (figure 2). A transponder is attached to each hen, either in the neck (Burel et al., 2002), on a wing (Marx et al., 2002), or on a leg (Thurner et al., 2006). When a hen uses an electronic nest, her transponder is detected by the antenna of the nest. Its ID, the ID of the visited nest (location), the time of access, and the time of presence are then recorded. If the hen lays an egg, it rolls behind the nest and triggers a sensor that records the laying time. By sorting the eggs by laying time (order of passage of the sensor), each egg can be allocated to the hen that laid it. These nests thus make it possible to measure egg-laying and egg quality traits (via egg-hen awarding) at the individual scale. In this review, the results obtained with an electronic nest described by Thurner et al. (2006) will be presented because it is the only one that has been the subject of several publications thus far.

Figure 2. Principle of the individual electronic nest.

Using electronic nests, Icken et al. (2008a) recorded the nesting behaviour of 272 RI hens reared in a floor pen with access to a winter garden. The number of eggs laid in nests measured over 12 periods of 28 days was found to be heritable, but heritability estimates varied with the age of the hens (between 0.05 at 9 months and 0.45 at 14 months). The estimated genetic correlation (Box 1) between the number of eggs laid in cages and the number of eggs laid in nests was also highly variable with hen age, ranging from strong positive values of between 0.56 and 0.97 during the first two months of egg-laying to lower estimates, between 0.22 and 0.44, at peak egg production (Icken et al., 2012). These genetic parameters, estimated on a small population, need to be clarified, but this original study may reveal the existence of genotype-environment interactions for egg production. The genetic correlation values different from 1 between cage and nest production may also be due to the significance of these two phenotypes; in the electronic nest, the hen's behaviour, i.e., her ability to go to the nest to lay eggs, is combined with her egg-laying capacity expressed in the cage. To improve egg production in cage-free systems, further studies are needed to improve knowledge of the nest laying behaviour traits of hens.

1.2. Off-nest laying

Eggs laid off-nest have to be collected by hand, which can be a laborious and time-consuming task for the farmer. They are often broken, eaten by the hens, or soiled with droppings and are usually downgraded or unmarketable. For breeders, eggs laid off-nest also have a lower fertility and hatchability rate than eggs laid in nests (Van den Brand et al., 2016). With the aim of improving working conditions and increasing the farmer's income, reducing off-nest laying is currently one of the major issues for cage-free systems.

Several environmental factors can have an effect on off-nest laying, including the environment before the start of laying, the characteristics of the laying house (nest structure, bedding, ventilation, etc.), the feed distribution at the laying time, and the lighting programme:

- the use of perches after the hens are four weeks old reduces off-nest laying from the start of laying to 35 weeks of age (Gunnarsson, 1999);

- hens prefer to lay eggs in wooden nests rather than in plastic nests (Van den Oever et al., 2020);

- observed in broiler breeders under feed restriction, feeding at the laying time causes hens to leave the nest without laying to feed and sometimes lay the egg off-nest (Sheppard and Duncan, 2011);

- off-nest laying is higher with a photoperiod of 11 or 12 hours compared to a photoperiod of 13 or 14 hours (Lewis et al., 2010).

In contrast, off-nest laying is also higher at the start of laying and decreases with age, probably because hens become accustomed to using nests (Cooper and Appleby, 1996; Settar et al., 2006; Oliveira et al., 2019). Studies using video recordings have found two categories of hens: hens that consistently lay off-nest and hens that consistently lay in nests (Cooper and Appleby, 1996; Kruschwitz et al., 2008; Zupan et al., 2008). In these studies, hens laying off-nest spent more time searching for a nest and exploring their environment in the hour before laying, compared to hens laying in nests, probably because the nests offered were not suitable. Finally, Settar et al. (2006) measured the number of eggs laid off-nest in 14,258 RI hens during 11 weeks from the start of laying. The hens were reared in floor pens of 18 sisters and/or sire-half-sisters. The study showed that the percentage of eggs laid off-nest per day and the percentage of eggs laid off-nest per week were heritable, with a heritability of 0.39 and 0.44, respectively. These heritability values give hope for substantial genetic progress in reducing the number of eggs laid off-nest. However, off-nest laying depends on many environmental factors, and genotype-environment interactions between the different cage-free systems need to be assessed. Identifying hens that lay off-nest is difficult and time-consuming (video recordings), and in large groups, it is not possible to routinely measure the number of eggs laid off-nest on an individual scale. Therefore, genetic improvement of this trait is likely to involve the use of indirect traits associated with pre-laying behaviour and nesting behaviour, for example.

2. Pre-laying behaviour

Pre-laying behaviour begins one to two hours before oviposition (egg-laying) and is initially characterised by increased activity with greater hen agitation and vocalisation (Wood-Gush and Gilbert, 1969; Meijsser and Hughes, 1989; Sherwin and Nicol, 1993). The hen then chooses a laying site and settles in. Once settled, the hen adopts a 'sitting' position, which she will alternate with nest-building activities, such as scratching the ground or litter, turning around in the nest, and collecting litter, if available, before laying her egg. Under natural conditions, the behaviour of searching for an egg-laying site would allow the hen to find a place that is safe from predators, as observed by Duncan et al. (1978). In this study, hens kept the same nest to lay all the eggs in a clutch (a sequence of consecutive days of laying) but systematically changed it between laying clutches and seasons, probably to protect themselves from predators and parasites.

In breeding, hens would generally use the same nest to lay eggs. Wall et al. (2004) recorded the behaviour of 35 transponder-equipped WL kept in cages with two collective nests. Consistency in nest choice averaged 90%, with a value of 50% indicating that the hen had no preference and 100% that the hen would always lay in the same nest. Consistency values in nest choice ranged from 54 to 100%, indicating variability for this trait. These results should be confirmed in cage-free systems with more nests. Furthermore, hens have a gregarious behaviour when laying eggs. If given the choice, they will prefer to lay in occupied nests rather than in free nests (Appleby and McRae, 1986; Riber, 2010; Tahamtani et al., 2018). This behaviour can have negative effects in terms of animal welfare, potentially increasing stress levels and the risk of suffocation in nests but also in terms of production by increasing off-nest laying (hens laying in front of occupied nests) and the number of broken eggs. Selecting hens that are able to go and lay in different nests far from each other could reduce the negative effects of gregarious laying behaviour. In the literature, there is no work on this trait, although electronic nests can measure it (by recording the nest ID and therefore the location). However, results have been published on winter garden exploratory behaviour and stereotypical behaviour prior to egg-laying.

Exploratory behaviour in a winter garden was studied in RI hens. Measured between 9 and 16 months of age, the frequency of passages and length of stay in the winter garden are heritable with estimated values of 0.24 for these two traits, which are also strongly genetically correlated (+0.82; Icken et al., 2008a). However, unfavourable genetic correlations were observed between the average length of stay and the number of eggs laid in nests (–0.34; Icken et al., 2008a), as well as the eggshell colour of RI (–0.54; Icken et al., 2011). The offspring of RI hens that spend the most time in the winter garden lay fewer eggs and have lighter coloured eggs compared to the offspring of hens that spend less time in the winter garden.

Regarding pre-laying behaviour, it is mainly stereotypical behaviour that has been the subject of genetic studies. These behaviours, such as severe pre-laying agitation and standing during laying, show that the hen cannot express her natural pre-laying behaviours and are indicators of malaise. Heil et al. (1990) measured the duration of pre-laying agitation, escape attempts in the five to ten minutes before laying (number of times the hen pokes her head out of the cage), and the position (sitting or standing) during laying by video recording individual cages. They found that the duration of agitation and escape attempts were weakly heritable (0.06 and 0.04, respectively), but position was moderately heritable (0.33). The results already observed on exploratory behaviour in the winter garden and on stereotypical behaviour prior to laying support the interest in studying the ability of hens to lay in different and distant nests. This trait may one day allow indirect selection against negative gregarious behaviour for laying and off-nest laying. In addition to pre-laying behaviour, nesting behaviour could also be exploited in selection to reduce off-nest laying.

3. Nesting behaviour

Two traits can be used to describe the nest-laying behaviour of the hen: the time of entry in nests and laying duration, i.e., the time spent in the nest for laying.

3.1. Time of entry in nests

Commercial hens, which are highly selected for egg production, tend to lay eggs over a relatively small time span. Lillpers (1991) estimated that the standard deviation of the laying time of a flock was less than 1 hour. Individual nests are mainly used in traditional backyard flocks. Most cage-free systems use collective nests. These large nests allow several hens to lay simultaneously in the same nest. There is potentially competition between hens at certain times to enter the nest. This can lead to choking and prevent some hens from entering the nest, forcing them to lay eggs off-nest. Increasing the number of nests per house or reducing the density of hens per nest may limit crowding problems at some point in the day, but would require either additional investment (increasing the size of the house to add more nests) or a decrease in production (fewer hens in the house). Other strategies using genetics can also be considered.

Heinrich et al. (2014) studied nesting behaviour in collective electronic nests. The principle of these nests is the same as that of individual electronic nests (figure 2). They are equipped with an antenna that can detect the presence of a hen via its transponder. However, collective electronic nests do not allow the identification of hens that lay eggs during their visit, nor do they allow the egg to be attributed to the hen that laid it, as several hens can use them simultaneously. Heinrich et al. (2014) compared the results with measurements made in individual electronic nests. They found that hens visited the nests 1.2 to 1.4 times per day, on average, and that there was little difference in this trait between measurements in collective nests and measurements in individual nests. Although the nests are intended for laying, some hens may use them without laying and several times during the day. Dominated hens may also use them as a refuge.

The genetic background of the time of entry in nests has been scarcely studied. This trait could potentially be exploited in selection, for example, to spread out the time of access to the hen's nest. The time of entry in nests to lay eggs is strongly dependent on the laying time (phenotypic correlation: +0.99; Bécot et al., 2021), which is a laying rhythm trait (see section 4.2.) and could be used as such for collective electronic nests where knowing the hen's laying time is not possible. Finally, Lillpers (1991) suggested using several genetic types in the same flock to extend the laying time of the hens and their period of nest use, but this requires ensuring that there is no aggressive behaviour between the genetic types.

3.2. Laying duration

Laying duration is the time spent in the nest for laying eggs. Measured in floor pens with electronic nests, the average laying duration is 30 min for RI and 45 min for WL (Icken et al., 2012). These authors observed that the duration in nests for visits without laying was shorter than the laying duration, with an average of 10 and 28 min for RI and WL, respectively. Heinrich et al. (2014) also observed that the average time spent in the nest per day per hen, whether laying or not, varied between 23 and 30 min in RI and between 42 and 69 min in WL, depending on age and the type of nest used (individual or collective nest). They noted that the nesting behaviour of RI varied little according to the type of nest used, unlike WL, which were more sensitive to changes in environment (change from collective nest to individual nest and vice-versa).

The genetic background of laying duration, like that of the duration of visits without laying, has been scarcely studied. Icken et al. (2013) measured laying duration in floor pens with electronic nests. For this trait, they estimated highly variable heritability values depending on the age of the hens, ranging from 0.10 at 7 months to 0.56 at 11 months. Reducing the laying duration of hens would reduce the nest occupancy rate, making nests more accessible and consequently reducing off-nest laying. However, to consider this trait in breeding programmes, genetic correlations with egg production and egg quality need to be studied, as well as genotype-environment interactions between individual and collective nest systems. In collective nests, social interactions are more frequent. Lundberg and Keeling (1999) studied the behaviour of WL reared in floor pens under a lighting programme of 13 h light and 11 h dark per day by video recording. The hens were placed in floor pens of 15 to 120 individuals with collective nests. These authors measured the time spent at the laying site (collective nest or a corner of the pen) of 130 hens at peak production (between 24 and 37 weeks of age) and the number of pecking blows given and received during laying. The more pecks the hen received from other hens, the less time she spent on her laying site. Conversely, the more pecks the hen received, the more time she spent on the laying site. No significant differences in hen behaviour between the different sized pens and the laying site (collective nest or corner of the pen) were observed. These results suggest that social interactions between dominant and dominated hens may have an effect on laying duration. It would be interesting to check whether they also have an effect on off-nest laying.

4. The laying rhythm

The laying rate and the number of eggs laid are complex traits controlled by the hen's laying rhythm. On average, it takes 24 to 26 hours from ovulation of the yolk to laying the egg (Sauveur, 1988; Box 2). Ovulations can occur daily, resulting in one egg being laid per day. Eggs laid on consecutive days form a clutch (Box 3). Each clutch is separated by days without laying, called pause days.

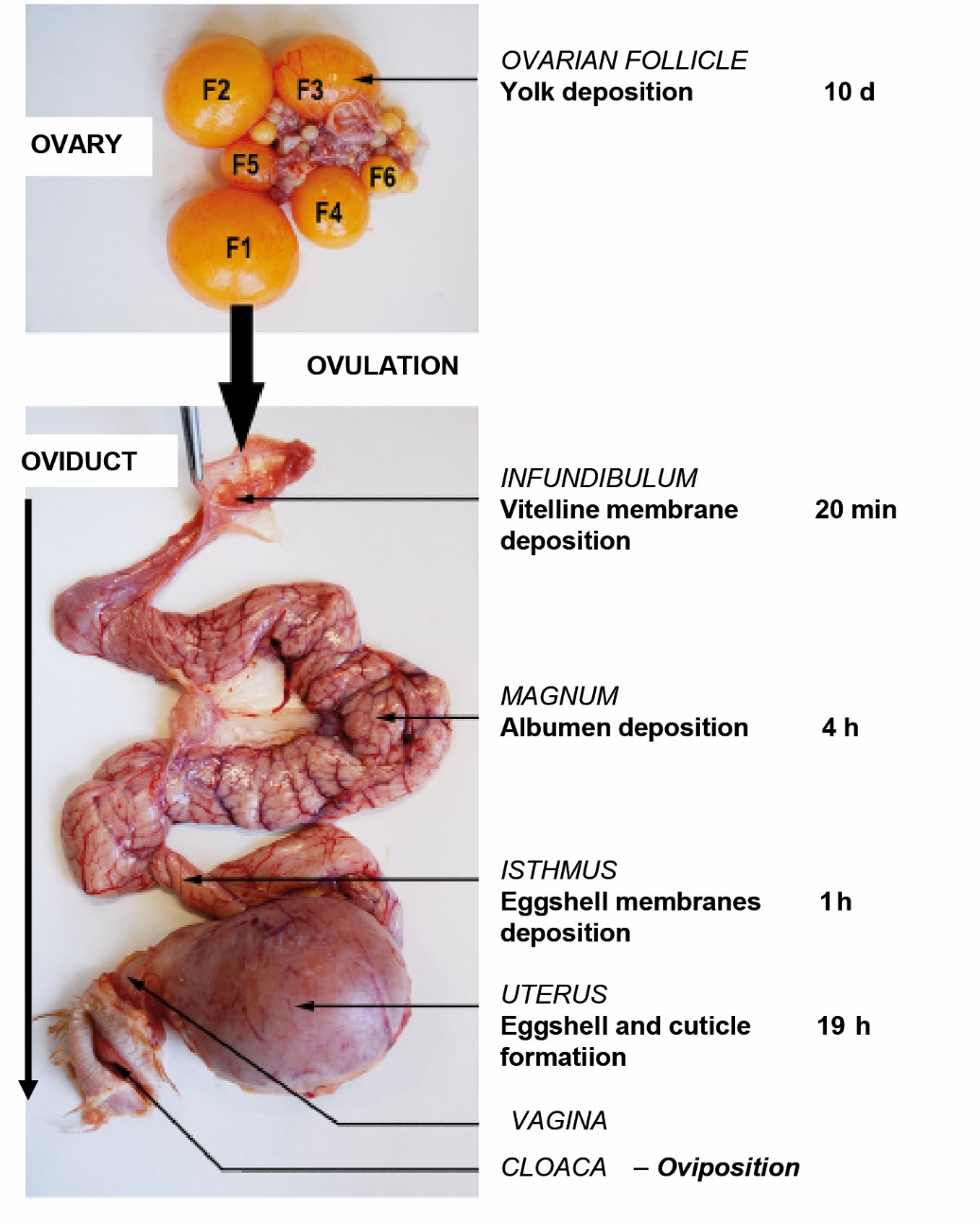

Box 2. Anatomy of the hen's reproductive system and egg formation.

The egg is a complex structure that contains all the components necessary for the development and protection of an embryo. It is synthesised in the female reproductive system, which is divided into two parts: the ovary and the oviduct. The oocyte or ‘yolk’ is produced in the ovary. When mature, it is released towards the oviduct, which is ovulation. The other components of the egg (vitelline membrane, albumen or ‘white,’ eggshell membranes, eggshell, and cuticle) are deposited in the oviduct. The oviduct is composed of five compartments: the infundibulum, magnum, isthmus, uterus, and vagina. After ovulation, the oocyte is taken up by the oviduct in the infundibulum. It takes about five hours for the yolk membrane, albumen, and eggshell membranes to settle around the yolk. The synthesis of the eggshell takes place mainly in the uterus. This stage takes about 19 hours. The cuticle is secreted at the end of eggshell formation. Oviposition or egg laying takes place about 24–26 h after ovulation (Sauveur, 1988; see Box 3).

Photo (INRAE) of the hen's reproductive system (ovary above and oviduct below) and summary of the stages of egg formation in each of the oviduct compartments (adapted from Nys and Guyot, 2011).

The average times of the different stages are given in hours. In the ovary, the pre-ovulatory follicles are numbered F1 to F6 in decreasing order of maturity (Johnson, 2015).

Box 3. The clutches.

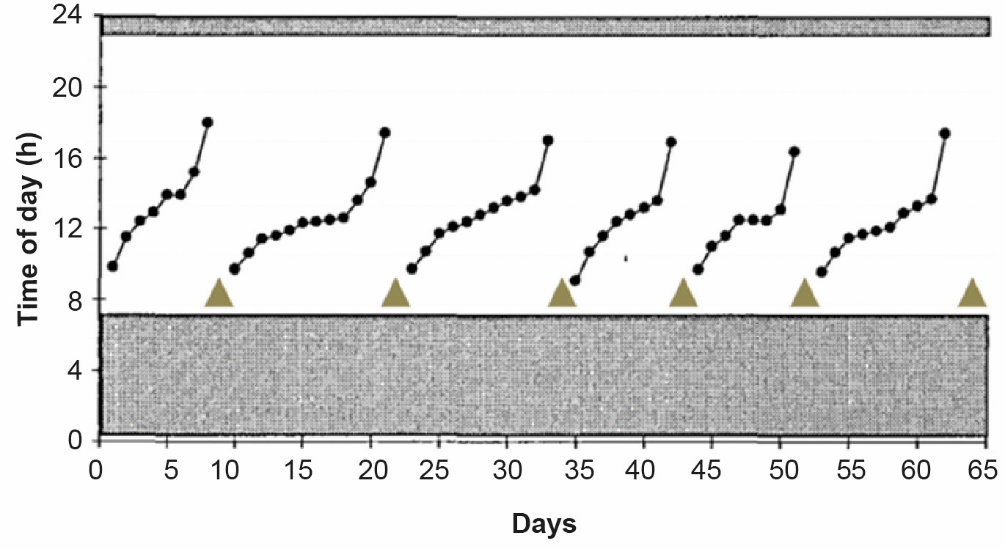

A clutch is a sequence of consecutive days with egg laying bounded by one or more days without egg laying. On average, it lasts about ten days. According to Sauveur (1988), the first egg of a clutch is laid early in the morning. Subsequent eggs are laid later and later, with the time interval between eggs laid in a clutch generally exceeding 24 h. The existence of clutches and pauses can be explained by the coordination between an external cycle of 24 h (circadian rhythm) and an endogenous cycle of follicular maturation that is generally longer than 24 h. These phenomena have been described in numerous reviews, such as Sauveur (1988 and 1996), Nys and Guyot (2011), and England and Ruhnke (2020). Briefly, ovulation is induced by a peak of luteinising hormone (LH; pituitary hormone) in the blood about 6 h before ovulation. This LH peak is dependent on the circadian rhythm and occurs after the light has gone out in the dark phase. In the ovary, a hierarchy of pre-ovulatory follicles leads to the presence of only one follicle ready to ovulate per cycle (Box 2). This follicle must have reached a sufficient maturity threshold for the LH peak to induce ovulation. A time lag accumulates from day to day if the follicle maturation cycle is longer than 24 hours, resulting in a shift in the laying time. When the maturity threshold is not sufficient at the time of the peak, the follicle must wait for the next day's LH peak to ovulate, leading the hen to pause for a day. The shorter the time intervals between laying, the longer the clutch. Today's laying hens, which are hyper-specialised for laying, can make clutches, not of about 10 days, but of more than 100 days.

Laying profile of a hen reared in an individual cage and having 6 clutches in 65 days (adapted from Lillpers and Wilhelmson, 1993a).

The light period is between 7 h and 23 h. The grey areas represent the dark period. Each dot represents one egg. Eggs from the same clutch are connected by a line. A pause day (day without laying) is symbolised by a triangle.

Several traits can define the laying rhythm, such as the length and number of clutches, the time interval between laying, and the laying time. These traits can be of interest for increasing egg production, both in cage and cage-free systems. In cage-free systems, the laying rhythm must also be controlled, as it is linked to the time of access to the hen's nest, which can lead to off-nest laying (see section 3.1.). The development of electronic nests makes it possible to record these traits in cage-free systems, and their genetic parameters have already been estimated, both in individual cages and in cage-free systems.

4.1. The length and number of clutches

The length and number of clutches could easily be measured in individual cages, as they only require counting the number of eggs each day, without the need to know their laying time. Three traits were mainly studied: the average and maximum clutch length and the clutch number. Wolc et al. (2019) measured clutches up to 90 weeks in 23,809 RI and 22,210 WL reared in individual cages and having characteristics close to current commercial hens. For RI and WL, these authors showed that the average clutch length per hen was 15.3 ± 9.9 (standard deviation) and 8.6 ± 4.4 eggs, respectively, and that the maximum clutch length was 81.8 ± 39.9 and 57.3 ± 33.5 eggs, respectively. The clutch number, measured over the same period, was 29.2 ± 16.9 (RI) and 43.4 ± 18.0 (WL). The increase in laying time and the time interval between laying was associated with clutch number increases and age and length decreases (Bednarczyk et al., 2000; Tumova et al., 2017; Wolc et al., 2019).

Average and maximum clutch lengths are weakly to moderately heritable in RI and WL (Table 1). For these two traits measured in individual cages, Wolc et al. (2019) estimated heritability values of 0.31 and 0.20 for RI, respectively, and 0.34 and 0.29 for WL, respectively. The clutch number was more highly heritable, with estimated values of 0.42 and 0.41 for RI and WL, respectively. More variable and generally lower heritability (between 0.03 and 0.40; Table 1) were nevertheless estimated for these three traits in other studies, involving the same breeds of hens and performance measured in individual cages (Bednarczyk et al., 2000; Akbas et al., 2002; Wolc et al., 2010) or measured in floor pens with electronic nests (Icken et al., 2008b). Heritability is a characteristic of a given population and environment that may explain the observed differences. For dwarf brown-egg laying hens, Chen and Tixier-Boichard (2003) also noted that the average and maximum clutch length have an asymmetric distribution. The estimation of heritability is based on the use of linear models. If the distribution of the residuals of the genetic model does not follow a normal distribution, it is necessary to transform the trait to obtain a variable whose distribution follows a normal distribution to avoid underestimating heritability. However, this asymmetry has not been reported in studies of commercial laying hen lines (Table 1).

Table 1. Heritability of clutch traits and genetic correlations (rg) with selection criteria.

Breed |

Number |

Age (weeks) |

Light |

Heritability (SE) |

rg (SE)–criterion |

Reference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Average clutch length |

|||||||

RI1 |

4,999 |

AFE4-38 |

14L:10D |

0.06/0.22 (0.03/0,07) |

+0.05/+0.54 |

EN5 |

|

AFE4-64 |

0.15/0.34 (0.04/0.08) |

+0.81/+0.90 |

EN5 |

||||

RI1 |

1,980 |

22-40 |

0.25/0.26 (0.04/0.07) |

+0.82 (0.05) |

EN5 |

||

+0.04 (0.12) |

PA6 |

||||||

RI1 |

272 |

20-70 |

16L:8D |

0.25 |

+0.64 |

EN5 |

|

RI1 |

4,122 |

AFE4-64 |

14L:10D |

0.23 (0.03) |

+0.13 |

LR387 |

|

+0.04 |

EW8 |

||||||

+0.12 |

BW6 |

||||||

RI1 |

23,809 |

AFE4-90 |

16L:8D |

0.31 (0.02) |

+0.57 (0.03) |

EN5 |

|

WL2 |

22,210 |

0.34 (0.02) |

+0.61 (0.03) |

EN5 |

|||

DB3 |

7,979 |

AFE4-42 |

16L:8D |

0.41/0.42 (0.02) |

+0.77 (0.02) |

EN5 |

|

+0.86 (0.01) |

LR7 |

||||||

–0.21 (0.03) |

EW8 |

||||||

–0.06 (0.03) |

BW6 |

||||||

Maximum clutch length |

|||||||

RI1 |

4,999 |

AFE4-38 |

14L:10D |

0.03/0.14 (0.03/0.08) |

+0.51/+0.58 |

EN5 |

|

AFE4-64 |

0.03/0.19 (0.03/0.07) |

+0.79/+0.80 |

EN5 |

||||

RI1 |

4,116 |

AFE4-64 |

14L:10D |

0.11 (0.02) |

+0.40 |

LR387 |

|

–0.13 |

EW8 |

||||||

–0.10 |

BW6 |

||||||

RI1 |

23,809 |

AFE4-90 |

16L:8D |

0.20 (0.01) |

+0.61 (0.03) |

EN5 |

|

WL2 |

22,210 |

0.29 (0.02) |

+0.45 (0.03) |

EN5 |

|||

DB3 |

5,826 |

AFE4-42 |

16L:8D |

0.41 (0.02) |

+0.77 (0.01) |

LR7 |

|

Clutch number |

|||||||

RI1 |

4,999 |

AFE4-38 |

14L:10D |

0.07/0.26 (0.03/0.07) |

–0.43/+0.38 |

EN5 |

|

AFE4-64 |

0.16/0.34 (0.04/0.08) |

–0.88/–0.74 |

EN5 |

||||

RI1 |

1,980 |

22-40 |

0.33/0.40 (0.05/0.10) |

–0.79 (0.10) |

EN5 |

||

–0.06 (0.11) |

BW6 |

||||||

RI1 |

272 |

20-70 |

16L:8D |

0.15 |

–0.53 |

EN5 |

|

RI1 |

4,118 |

AFE4-64 |

14L:10D |

0.23 (0.04) |

–0.08 |

LR387 |

|

–0.02 |

EW8 |

||||||

–0.13 |

BW6 |

||||||

RI1 |

23,809 |

AFE4-90 |

16L:8D |

0.42 (0.02) |

–0.55 (0.01) |

EN5 |

|

WL2 |

22,210 |

0.41 (0.02) |

–0.28 (0.01) |

EN5 |

|||

DB3 |

5,826 |

AFE4-42 |

16L:8D |

0.46 (0.02) |

–0.54 (0.05) |

LR7 |

|

Genetic correlations: favourable—null—unfavourable.

Light (L: light duration [h]; D: dark duration [h]) and standard errors (SE) are specified if they are mentioned in the studies. ‘/’ indicates a range of variation between extreme values.

1 RI: Rhode Island; 2 WL: White Leghorn; 3 DB: dwarf brown egg laying hens; 4 AFE: age at laying the first egg; 5 EN: egg number; 6 BW: body weight; 7 LR: laying rate measured over the period indicated in the age column or from the age at laying the first egg to 38 weeks (LR38); 8 EW: egg weight; 9 Hens kept in floor pens with electronic nests, individual cage trait (other studies; 10 Standardised trait (Box-Cox transformation; Chen and Tixier-Boichard, 2003).

The genetic correlations between the average and maximum clutch length are strong and positive (between +0.88 and +0.99; Table 2). The genetic correlations between these two traits and the clutch number are strong and negative (between –0.99 and –0.74; Table 2). These correlations indicate that hens with the genetic potential to lay long clutches on average also have the genetic potential to lay a long maximum clutch and the genetic potential to lay a small clutch number (few pauses) during their career. The average and maximum clutch length are genetically strongly correlated with the number of eggs laid and the laying rate (between +0.40 and +0.90; Table 1). The genetic correlations are moderate to strong and negative between these two egg production traits and the clutch number (between –0.88 and –0.28; Table 1). However, for the 1996/1997 generation of RI reared in individual cages, Bednarczyk et al. (2000) estimated a neutral (+0.05) and unfavourable (+0.38) genetic correlation between the number of eggs laid up to 38 weeks and the average clutch length and the clutch number, respectively. The hens of this generation lay very well at the beginning of their career (113 eggs, on average, at 38 weeks), which may be the reason for the observation of such correlations.

Table 2. Genetic correlations (rg) between egg-laying rate traits.

Trait A |

Trait B |

rg (A–B) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

avgC1 |

maxC2 |

+0.88/+0.99 |

Bednarczyk et al. (2000); Chen and Tixier-Boichard (2003); Wolc et al. (2010); Wolc et al. (2019) |

CN3 |

–0.99/–0.83 |

Bednarczyk et al. (2000); Akbas et al. (2002); Chen and Tixier-Boichard (2003); Icken et al. (2008b); Wolc et al. (2010); Wolc et al. (2019) |

|

avgTI4 |

–0.57/–0.56 |

||

maxC2 |

CN3 |

–0.98/–0.74 |

Bednarczyk et al. (2000); Chen and Tixier-Boichard (2003); Wolc et al. (2010); Wolc et al. (2019) |

avgTI4 |

–0.32 |

||

CN3 |

avgTI4 |

+0.54/+0.58 |

|

avgTI4 |

avgLT5 |

+0.51/+0.81 |

The ‘/’ indicates a range of variation between extreme values. 1 avgC: average clutch length; 2 maxC: maximum clutch length; 3 CN: clutch number; 4 avgTI: average time interval between egg-laying; 5 avgLT: average laying time.

Overall, these results suggest that selecting hens with long clutches and a small clutch number, and therefore few pauses, over their career would indirectly increase egg production. This was observed by Chen and Tixier-Boichard (2003). They studied two dwarf lines of brown-egg laying hens, with or without the naked neck gene, and selected for 16 generations on the average clutch length. The authors of this study showed that selecting hens with a higher average clutch length improved egg production. However, Chen and Tixier-Boichard (2003) estimated a negative genetic correlation of –0.21 between average clutch length and egg weight (Table 1). On a more recent RI line, Wolc et al. (2010) estimated neutral genetic correlations between clutch traits and egg weight (between –0.02 and +0.05; Table 1) and body weight (between –0.13 and +0.12; Table 1). Further studies are needed to verify the genetic relationships between clutch traits and egg quality in commercial lines bred in cage-free systems. The effects of such selection on hen welfare will also need to be assessed, as selection for egg production is already associated with an increase in violent behaviour, such as pecking or cannibalism (Tixier-Boichard, 2020).

Wolc et al. (2019) also attempted to better understand the genetic architecture of clutch traits by studying the proportion of genetic variance explained by 1 Mb windows with GWAS (Box 1). The study identified 4 QTL affecting the average clutch length (2 in RI located on chromosomes 1 and 8; 2 in WL located on chromosomes 6 and 18) and 2 QTL in WL affecting the maximum clutch length, located on chromosomes 2 and 6. These QTL explained between 1.00 and 3.95% of the genetic variance for each trait. Five QTL affecting the clutch number (2 in RI located on chromosomes 1 and 2; 3 in WL, two of which were located on chromosome 3 and one on chromosome 6), explaining between 1.18 and 7.07% of the genetic variance of the trait, were also identified. The QTL were line and trait specific, except the one located on chromosome 6 (between 28 and 29 Mb), affecting the average clutch length and clutch number in WL. Wolc et al. (2019) noted that 4 genes located at the QTL for the clutch number are involved in reproductive functions (NPVF, SRD5A2, and FOXO3) or in light perception (NR2E1).

4.2. The time interval between laying and the laying time

In contrast to the length and number of clutches, the time interval between laying and the laying time are more difficult to measure, as they require precise knowledge of the laying time of the hens. This can be achieved by using sensors, such as those in electronic nests (figure 2). Ovulation occurs 15 to 45 min after the previous egg is laid (Nys and Guyot, 2011). As the time of ovulation cannot be easily determined, the time interval between laying, i.e., the time between the laying time of two consecutive laying days, is often measured in studies. The average time interval between laying is between 24 and 26 h (Lillpers and Wilhelmson, 1993a; Chen et al., 2007; Roy et al., 2014). However, greater variability has been observed for this trait; in approximately 1,370 RI reared in individual cages, Wolc et al. (2010) measured a minimum average time interval between laying per hen of 21 h 02 min ± 1 h 22 min and a maximum average of 27 h 17 min ± 1 h 22 min. In some hens, ovulation may occur slightly before laying of the previous egg, which may explain laying intervals of less than 24 h (Nys and Guyot, 2011). In batches of 272 hens reared in floor pens with electronic nests, Icken et al. (2008b) observed an average time interval between laying of 24 h 06 min ± 37 min for one batch of RI and between 24 h 05 min ± 38 min and 24 h 10 min ± 43 min for three batches of WL. In individual cages with a light duration of at least 15 h 15 min per day, the average time interval between laying is highly heritable (between 0.42 and 0.66; Table 3). However, Wolc et al. (2010) observed a lower heritability for this trait (0.13) recorded on hens subjected to a lighting programme of 14 h light and 10 h dark per day. Icken et al. (2008b) also estimated a low heritability (0.09) on a batch of 272 RI reared in floor pens with electronic nests.

Table 3. Heritability of temporal egg-laying rhythm traits and genetic correlations (rg) with selection criteria.

Breed |

Number |

Age |

Light |

Heritability (SE) |

rg (SE)–criterion |

Reference |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Average time interval between laying |

|||||||

RI1 |

272 |

20-70 |

16L:8D |

0.09 |

–0.29 |

EN4 |

|

RI1 |

1,369 |

AFE3-64 |

14L:10D |

0.13 (0.05) |

–0.37 |

LR385 |

|

–0.16 |

EW6 |

||||||

+0.10 |

BW7 |

||||||

RI1 |

158 |

31-51 |

16L:8D |

0.42 (0.23) |

–0.62 |

EN4 |

|

–0.97 |

EN704 |

||||||

–0.04 and –0.05 |

EW6 |

||||||

WL2 |

155 |

0.52 (0.21) |

+0.04 |

EN4 |

|||

+0.05 |

EN704 |

||||||

–0.18 and –0.03 |

EW6 |

||||||

WL2 |

158 |

0.55 (0.24) |

–0.92 |

EN704 |

|||

+0.10 and +0.57 |

EW6 |

||||||

WL2 |

2,829 |

30-34 |

15:15L: |

0.47/0.66 (0.05/0.10) |

–0.61 (0.07) |

LR435 |

|

–0.74 (0.05) |

LR645 |

||||||

+0.38 (0.05) |

EW6 |

||||||

+0.20 (0.05) |

BW7 |

||||||

Average laying time |

|||||||

RI1 |

158 |

31-51 |

16L:8D |

0.72 (0.23) |

–0.20 |

EN4 |

|

–0.80 |

EN704 |

||||||

–0.36 and +0.08 |

EW6 |

||||||

WL2 |

155 |

0.19 (0.17) |

+0.27 |

EN4 |

|||

–0.04 |

EN704 |

||||||

–0.54 and –0.53 |

EW6 |

||||||

WL2 |

158 |

0.81 (0.20) |

–0.40 |

EN4 |

|||

–0.74 |

EN704 |

||||||

+0.01 and +0.03 |

EW6 |

||||||

WL2 |

2,829 |

30-34 |

15:15L: |

0.43/0.57 (0.05/0.10) |

–0.49 (0.08) |

LR435 |

|

–0.66 (0.07) |

LR645 |

||||||

+0.20 (0.06) |

EW6 |

||||||

+0.00 (0.06) |

BW7 |

||||||

Genetic correlations: favourable—null—unfavourable.

Light (L: light duration [h]; D: dark duration [h]) and standard errors (SE) are specified if they are mentioned in the studies. ‘/’ indicates a range of variation between the extreme values.

1 RI: Rhode Island; 2 WL: White Leghorn; 3 AFE: age at first egg laid; 4 EN: number of eggs laid measured over the period indicated in the age column or from age at laying the first egg to 70 weeks (EN70); 5 LR: laying rate measured from age at laying the first egg to 38, 43, or 64 weeks; 6 EW: egg weight; 7 BW: body weight; 8 Hens kept in floor pens with electronic nests, individual cage for other studies.

In individual cages and for the same lighting programme, RI lay 1 h earlier, on average, than WL (Lewis et al., 1995; Tumova et al., 2017). The laying time can vary depending on the rearing conditions and the line. Icken et al. (2012) observed a greater difference in floor pens with electronic nests in hens subjected to a conventional light programme of 16 h light and 8 h dark per day. RI reached peak production 3 h, on average, after the lights were turned on, while WL reached it 6 h after the lights were turned on. Using the same lighting programme, Lillpers and Wilhelmson (1993a) studied two WL lines and one RI line reared in individual cages. The WL line that was selected on egg mass and the RI line that was selected on egg mass and feed consumption laid on average 6 h 30 min ± 42 min and 5 h 30 min ± 1 h after the lights were turned on, respectively. The average laying time for these two lines was highly heritable (0.72 and 0.81; Table 3). In contrast, the heritability of this trait was 0.19 for the third line, a WL line, selected for the number of laid eggs, laid eggs 5 h 36 min ± 1 h, on average, after the lights were turned on. For a population of WL hens reared in individual cages with 15 h 25 min of light per day, Yoo et al. (1988) also measured an average laying time of 5 h 19 min ± 1 h 13 min after the lights were turned on and estimated a heritability between 0.43 and 0.57 for this trait (Table 3).

The time interval between laying increased significantly with age (Lillpers and Wilhelmson, 1993b), as did the laying time (Tumova and Gous, 2012; Tumova et al., 2017). Hens that laid later in the day had lower egg production (Icken et al., 2008b). Genetically, the average time interval between laying was positively correlated with the average laying time, between +0.51 and +0.81 (Table 2). Moderate to strong negative genetic correlations were also estimated between these two traits and the traits of laying rate and number of laid eggs (between –0.97 and –0.20; Table 3), indicating that egg production could be increased by selecting hens with a small average time interval and those that laid eggs early in the day. However, genetic correlations were null to positive, between –0.04 and +0.27, for the WL line selected based on the number of laid eggs (Lillpers and Wilhelmson, 1993a; Table 3).

Knowledge about the phenotypic and genetic relationships between these temporal traits and egg qualities is partial. The eggshell colour study of 150 RI showed that eggs laid later in the day were lighter in colour, on average (Samiullah et al., 2016). Eggs laid in the afternoon had a lower egg weight, on average (Tumova et al., 2007). The estimated genetic correlations in individual cages between egg weight and the traits of average time interval between laying and average laying time (between –0.54 and +0.38; Table 3) varied greatly depending on the study and the line, making their interpretation tricky. These genetic correlations also need to be estimated in cage-free systems.

4.3. Pause duration

At the flock level, one or more days' pause per hen can result in a significant deficit in the number of eggs collected and marketed. In wild poultry species, stopping laying at the end of a clutch generally leads to brooding, a behaviour naturally selected for their survival (Guémené et al., 2001). This behaviour has almost completely disappeared in current commercial laying hen lines. Roy et al. (2014) studied a population of 1,216 WL hens reared in individual cages with a lighting programme of 14 h light and 10 h dark per day until 40 weeks of age. They found that the total number of pause days averaged 23.67 for an average clutch number (equivalent to the number of pauses) of 12.69, or about 1.9 days per pause. For hens reared in floor pens with electronic nests up to about 70 weeks, Icken et al. (2012) found that pauses of 1, 2, and 3 days accounted for 61–65%, 16–20%, and 6–7% of pauses, respectively. Pauses longer than 4 days occurred mostly during a period of infection of the batch. However, it is necessary to differentiate between one-day and multi-day pauses. One-day pauses are related to a shift in the follicular maturation cycle (see Box 3). The mechanisms explaining pauses of more than one day are poorly understood and still need to be studied with the aim of reducing them by environmental control or selection. Notably, two-day pauses could be the consequence of a reduced rate of follicular maturation (Robinson et al., 1990). The pause duration increases with age (Robinson et al., 1990), and individual differences in hormonal control of reproduction may explain how some hens are able to maintain high persistency in laying eggs, while others are not (Bain et al., 2016). The number of pauses is, by definition, similar to the clutch number, which could be exploited in selection to increase egg production (see section 4.1.).

Conclusion

The possible recording of pre-laying behaviour and nesting behaviour traits in cage-free systems offers prospects for selecting laying hens against off-nest laying. With heritability estimates often higher than egg production and favourable genetic correlations, the traits of the laying rhythm could also be used in selection, with the aim of increasing egg production per hen in cage-free systems. In contrast to the length and number of clutches, the time interval between laying and the laying time seems to be easier to measure with electronic nests because they do not require the total number of eggs laid, which also depends on the number of eggs laid off-nest (unknown). Selection based on the average laying time could nevertheless contribute to reducing the variability of laying time in the lines and thus the time of entry in nests, increasing competition and the risk of off-nest laying. Further studies, especially in cage-free systems, are needed to better understand the relationships between egg-laying traits and egg quality before considering their inclusion in breeding programmes. The relationships between these traits and resistance to pathogens, as well as the hen's microbiota, response to stress, and social behaviour, particularly aggressiveness and dominance, need to be studied to ensure that they are not degraded. The accuracy of heritability estimates and genetic correlations of egg-laying traits in cage-free systems needs to be improved with measurements on larger numbers. The extent of genotype-environment interactions between individual and collective nest systems and between various environments representative of cage-free systems (temperature, humidity, duration of lighting, outdoor access or not, feeding, etc.) must also be estimated. Finally, the consequences of crossbred individuals, i.e., on commercial hens resulting from selection, must be evaluated.

Acknowledgments

This article was first translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator and the authors used Proof-Reading Service (http://www.proof-reading-service.com) for English language editing.

References

- Akbas Y., Unver Y., Oguz I., Altan O., 2002. Comparison of different variance component estimation methods for genetic parameters of clutch pattern in laying hens. Arch. Geflügelk., 66, 232-236.

- Appleby M.C., McRae H.E., 1986. The individual nest box as a super-stimulus for domestic hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 15, 169-176.

- Bain M.M., Nys Y., Dunn I.C., 2016. Increasing persistency in lay and stabilising egg quality in longer laying cycles. What are the challenges? Br. Poult. Sci., 57, 330-338.

- Beaumont C., Calenge F., Chapuis H., Fablet J., Minvielle F., Tixier-Boichard M., 2010. Génétique de la qualité de l’œuf. In : Numéro spécial, Qualité de l’œuf. Nys Y. (Ed). INRA Prod. Anim., 23, 123-132.

- Bécot L., Bédère N., Burlot T., Coton J., Le Roy P., 2021. Nest acceptance, clutch, and oviposition traits are promising selection criteria to improve egg production in cage-free system. PLOS ONE, 16(5), e0251037.

- Bednarczyk M., Kieclzewski K., Szwaczkowski T., 2000. Genetic parameters of the tradtitional selection traits and some clutch traits in a commercial line of laying hens. Arch. Geflügelk., 64, 129-133.

- Burel C., Ciszuk P., Wiklund B.S., Kiessling A., 2002. Note on a method for individual recording of laying performance in groups of hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 77, 167-171.

- Chen C., Tixier-Boichard M., 2003. Correlated responses to long-term selection for clutch length in dwarf brown-egg layers carrying or not carrying the naked neck gene. Poult. Sci., 82, 709-720.

- Chen C.F., Shiue Y.L., Yen C.J., Tang P.C., Chang H.C., Lee Y.P., 2007. Laying traits and underlying transcripts, expressed in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland that were associated with egg production variability in chickens. Theriogenology, 68, 1305-1315.

- Commission Européenne, 2021. Market situation for eggs. https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/animals-and-animal-products/animal-products/eggs_en

- Cooper J.J., Appleby M.C., 1996. Individual variation in prelaying behaviour and the incidence of floor eggs. Br. Poult. Sci., 37, 245-253.

- Coudurier B., 2011. Contraintes et opportunités d’organisation de la sélection dans les filières porcine et avicole. In : Amélioration génétique. Mulsant P., Bodin L., Coudurier B., Deretz S., Le Roy P., Quillet E., Perez J.M. (Eds). INRA Prod. Anim., 24, 307-322.

- Duncan I.J.H., Savory C.J., Wood-Gush D.G.M., 1978. Observations on the reproductive behaviour of domestic fowl in the wild. Appl. Anim. Ethol., 4, 29-42.

- England A., Ruhnke I., 2020. The influence of light of different wavelengths on laying hen production and egg quality. World’s Poult. Sci. J., 1-16.

- Guémené D., Kansaku N., Zadworny D., 2001. L’expression du comportement d’incubation chez la dinde et sa maîtrise en élevage. INRA Prod. Anim., 14, 147-160.

- Gunnarsson S., 1999. Effect of rearing factors on the prevalence of floor eggs, cloacal cannibalism and feather pecking in commercial flocks of loose housed laying hens. Br. Poult. Sci., 40, 12-18.

- Heil G., Simianer H., Dempfle L., 1990. Genetic and phenotypic variation in prelaying behavior of Leghorn hens kept in single cages. Poult. Sci., 69, 1231-1235.

- Heinrich A., Icken W., Thurner S., Wendl G., Bernhardt H., Preisinger R., 2014. Nesting behavior - a comparison of single nest boxes and family nests. Eur. Poult. Sci., 78, 1-15.

- Icken W., Cavero D., Schmutz M., Thurner S., Wendl G., Preisinger R., 2008a. Analysis of the free range behaviour of laying hens and the genetic and phenotypic relationships with laying performance. Br. Poult. Sci., 49, 533-541.

- Icken W., Cavero D., Schmutz M., Thurner S., Wendl G., Preisinger R., 2008b. Analysis of the time interval within laying sequences in a transponder nest. Proceedings 23th World’s Poult. Congr. Brisbane, Australia, 64, 231-234.

- Icken W., Cavero D., Thurner S., Schmutz M., Wendl G., Preisinger R., 2011. Relationship between time spent in the winter garden and shell colour in brown egg stock. Arch. Geflügelk., 75, 145-150.

- Icken W., Cavero D., Schmutz M., Preisinger R., 2012. New phenotypes for new breeding goals in layers. World’s Poult. Sci. J., 68, 387-400.

- Icken W., Thurner S., Heinrich A., Kaiser A., Cavero D., Wendl G., Fries R., Schmutz M., Preisinger R., 2013. Higher precision level at individual laying performance tests in noncage housing systems. Poult. Sci., 92, 2276-2282.

- ITAVI, 2019. Situation du marché des œufs et ovoproduits - édition novembre 2019. 11p.

- Johnson A.L., 2015. Ovarian follicle selection and granulosa cell differentiation. Poult. Sci., 94, 781-785.

- Kruschwitz A., Zupan M., Buchwalder T., Huber-Eicher B., 2008. Nest preference of laying hens (Gallus gallus domesticus) and their motivation to exert themselves to gain nest access. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 112, 321-330.

- Lewis P.D., Perry G.C., Morris T.R., 1995. Effect of photoperiod on the mean oviposition time of two breeds of laying hen. Br. Poult. Sci., 36, 33-37.

- Lewis P.D., Danisman R., Gous R.M., 2010. Photoperiods for broiler breeder females during the laying period. Poult. Sci., 89, 108-114.

- Lillpers K., 1991. Genetic variation in the time of oviposition in the laying hen. Br. Poult. Sci., 32, 303-312.

- Lillpers K., Wilhelmson M., 1993a. Genetic and phenotypic parameters for oviposition pattern traits in three selection lines of laying hens. Br. Poult. Sci., 34, 297-308.

- Lillpers K., Wilhelmson M., 1993b. Age-dependent changes in oviposition pattern and egg production traits in the domestic hen. Poult. Sci., 72, 2005-2011.

- Lundberg A., Keeling L.J., 1999. The impact of social factors on nesting in laying hens (Gallus gallus domesticus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 64, 57-69.

- Marx G., Klein S., Weigend S., 2002. An automated nest box system for individual performance testing and parentage control in laying hens maintained in groups. Arch. Geflügelk., 66, 141-144.

- Meijsser F.M., Hughes B.O., 1989. Comparative analysis of pre‐laying behaviour in battery cages and in three alternative systems. Br. Poult. Sci., 30, 747-760.

- Nys Y., Guyot N., 2011. Improving the safety and quality of eggs and egg products: volume 1: egg chemistry, production and consumption. In: 6 - Egg formation and chemistry. Elsevier, 83-132.

- Oliveira J.L., Xin H., Chai L., Millman S.T., 2019. Effects of litter floor access and inclusion of experienced hens in aviary housing on floor eggs, litter condition, air quality, and hen welfare. Poult. Sci., 98, 1664-1677.

- Riber A.B., 2010. Development with age of nest box use and gregarious nesting in laying hens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 123, 24-31.

- Robinson F.E., Hardin R.T., Robblee A.R., 1990. Reproductive senescence in domestic fowl: Effects on egg production, sequence length and inter‐sequence pause length. Br. Poult. Sci., 31, 871-879.

- Romé H., Le Roy P., 2016. Régions chromosomiques influençant les caractères de production et de qualité des œufs de poule. INRA Prod. Anim., 29, 117-128.

- Roy B.G., Kataria M.C., Roy U., 2014. Study of oviposition pattern and clutch traits in a White Leghorn (WL) layer population. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci., 7, 59-67.

- Samiullah S., Roberts J., Chousalkar K., 2016. Oviposition time, flock age, and egg position in clutch in relation to brown eggshell color in laying hens. Poult. Sci., 95, 2052-2057.

- Sauveur B., 1988. Reproduction des volailles et production d’œufs. INRA Éditions, Paris, France, 480p.

- Sauveur B., 1996. Photopériodisme et reproduction des oiseaux domestiques femelles. In: Numéro special, Photopériode et reproduction. INRA Prod. Anim., 9, 25-34.

- Settar P., Arango J., Arthur J., 2006. Evidence of genetic variability for floor and nest egg laying behavior in floor pens. Proc. 12th Eur. Poult. Conf. Verona, Italy, 1-3.

- Sheppard K.C., Duncan I.J.H., 2011. Feeding motivation on the incidence of floor eggs and extraneously calcified eggs laid by broiler breeder hens. Br. Poult. Sci., 52, 20-29.

- Sherwin C.M., Nicol C.J., 1993. A descriptive account of the pre-laying behaviour of hens housed individually in modified cages with nests. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 38, 49-60.

- Tahamtani F.M., Hinrichsen L.K., Riber A.B., 2018. Laying hens performing gregarious nesting show less pacing behaviour during the pre-laying period. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 202, 46-52.

- Thurner S., Wendl G., Preisinger R., 2006. Funnel nest box: a system for automatic recording of individual performance and behaviour of laying hens in floor management. Proc. 12th Eur. Poult. Conf. Verona, Italy, 1-6.

- Tixier-Boichard M., 2020. From the jungle fowl to highly performing chickens: are we reaching limits? World’s Poult. Sci. J., 76, 2-17.

- Tumova E., Zita L., Hubeny M., Skrivan M., Ledvinka Z., 2007. The effect of oviposition time and genotype on egg quality characteristics in egg type hens. Czech J. Anim. Sci., 52, 26-30.

- Tumova E., Gous R.M., 2012. Interaction of hen production type, age, and temperature on laying pattern and egg quality. Poult. Sci., 91, 1269-1275.

- Tumova E., Uhlirova L., Tuma R., Chodova D., Machal L., 2017. Age related changes in laying pattern and egg weight of different laying hen genotypes. Anim. Reprod. Sci., 183, 21-26.

- Van den Brand H., Sosef M.P., Lourens A., Van Harn J., 2016. Effects of floor eggs on hatchability and later life performance in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci., 95, 1025-1032.

- Van den Oever A.C.M., Rodenburg T.B., Bolhuis J.E., Van de Ven L.J.F., Hasan Md.K., Van Aerle S.M.W., Kemp B., 2020. Relative preference for wooden nests affects nesting behaviour of broiler breeders. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 222, 1-7.

- Wall H., Tauson R., Elwinger K., 2004. Pop hole passages and welfare in furnished cages for laying hens. Br. Poult. Sci., 45, 20-27.

- Wolc A., Bednarczyk M., Lisowski M., Szwaczkowski T., 2010. Genetic relationships among time of egg formation, clutch traits and traditional selection traits in laying hens. J. Anim. Feed Sci., 19, 452-459.

- Wolc A., Jankowski T., Arango J., Settar P., Fulton J.E., O’Sullivan N.P., Dekkers J.C.M., 2019. Investigating the genetic determination of clutch traits in laying hens. Poult. Sci., 98, 39-45.

- Wood-Gush D.G.M., Gilbert A.B., 1969. Oestrogen and the pre-laying behaviour of the domestic hen. Anim. Behav., 17, 586-589.

- Yoo B.H., Sheldon B.L., Podger R.N., 1988. Genetic parameters for oviposition time and interval in a white leghorn population of recent commercial origin. Br. Poult. Sci., 29, 627-637.

- Zupan M., Kruschwitz A., Buchwalder T., Huber-Eicher B., Stuhec I., 2008. Comparison of the prelaying behavior of nest layers and litter layers. Poult. Sci., 87, 399-404.

Abstract

The number of laying hens raised in cage-free systems has increased in Europe. In these breeding systems, hens live freely in large groups and must lay eggs in nests. Breeders need to measure the individual laying performance of hens under these very different cage conditions. To do so, electronic nests have been developed. These nests enable to measure regular selection criteria, i.e. egg production and egg quality traits, but also provide access to new egg-laying traits, related to pre-laying behavior and nesting behavior. Reproductive rhythm traits can also be measured precisely by recording the laying time. Although there is little knowledge of the genetic background of these egg-laying traits, there are already selection opportunities for increasing egg-laying performance in these breeding systems as well as improved adaptation capacity and welfare.

Attachments

No supporting information for this article##plugins.generic.statArticle.title##

Views: 16085

Views: 16085

Downloads

XML: 43

XML: 43

PDF: 76

PDF: 76

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Pascale LE ROY, Alain DUCOS, Florence PHOCAS, What performance for tomorrow’s animals? Breeding goals and selection methods , INRAE Productions Animales: Vol. 32 No. 2 (2019): Volume 32 Issue 2: Special Issue. Major challenges and solutions for livestock farming