Header

Ruminant microbes are of growing interest in farm management and animal selection. What are the main factors that really affect them? Can they be modified to improve the health and efficiency of farm ruminants? 1

Introduction

The ruminant, like other complex organisms, constructs and maintains close links with the multiple microorganisms that colonize it and constitute its microbiota. The combination of the host organism (here the animal) and the cohort of microorganisms it hosts constitute a living entity called a holobiont (from the Greek hólos, everything, and bios, life). The microbiome corresponds to all these microorganisms and their genomes, habitat and surrounding conditions ([Marchesi and Ravel, 2015]). In ruminants, microbes are housed in different habitats: on the skin, particularly the teat ([Frétin et al., 2018]) and the interdigital space ([Zinicola et al., 2015]), and in the digestive, respiratory and genital tracts, etc. ([Swartz et al., 2014]; [Tapio et al., 2016]; [Zeineldin et al., 2019]). These microbes are of great importance for the physiology ([Alipour et al., 2018]) and health ([Nicola et al., 2017]) of the animal; they contribute both to zootechnical performance ([Li et al., 2019]; [Ramayo-Caldas et al., 2019]) and product quality ([Frétin et al., 2018]). In particular, the ruminal microbiota, which is composed mainly of bacteria and protozoa but also archaea and fungi, plays a central role in the nutrition and health of its host. This is particularly true because the rumen is located upstream of the absorption sites. The ruminal microbiota, therefore, is crucial in the nutrition of its host through the valorization of parietal carbohydrates. It provides 70% of the host's daily energy requirement and synthesizes essential amino acids and vitamins ([Bergman, 1990]). The anatomical position of the rumen makes its microbiota more sensitive to environmental factors than are downstream digestive microbes. The main factors that affect variation of the ruminant microbiota are the environment, including feed and husbandry practices, and the host, including age and genetics.

After a brief presentation of the composition of ruminant microbiotas, we will detail the potential contributions of new analytical approaches reported in recent studies on the factors that affect microbiota variation. Then the relationships between those factors and traits of interest to farmers because of the relationship to animal health, welfare and performance will be discussed.

1. Microbiotas in ruminants

In ruminants, complex and diverse microbial communities are present in different sites, including the digestive tract and in particular the rumen. As a dynamic ecosystem, the rumen is by far the most studied. Its microbes interact with each other during the degradation of complex carbohydrates in the plant cell wall that are little used by humans ([Huws et al., 2018]). Symbiotic digestive microbes (rumen and intestine) play an essential role in the animal–host interaction with the environment by providing nutrients and stimulating the immune system. In this review, we will focus on digestive and udder-associated microbes (see figure 1) primarily from cattle, the most studied ruminant species.

1.1. Study methods

Since the pioneering work of R. Hungate (1966a, b), our ability to cultivate anaerobic microorganisms has improved through the development of specific culture media and high throughput tools ([Kenters et al., 2011]; [Borrel et al., 2014]). However, although new microorganisms are constantly being discovered and cultured, many bacteria, archaea ([Creevey et al., 2014]), fungi ([Seshadri et al., 2018]) and especially protozoa ([Firkins et al., 2020]) have not yet been cultivated. Efforts to obtain new isolates are continuing, in particular with the Hungate 1000 Project, which is attempting to sequence the genome of 1,000 strains of bacteria and archaea to determine their functional potentials ([Seshadri et al., 2018]).

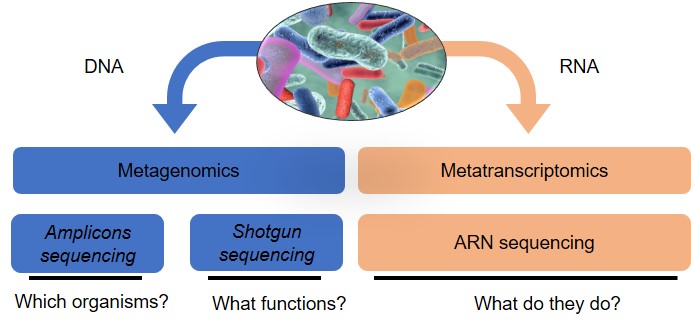

The rise of next-generation sequencing has led to an explosion of studies on the metataxonomy (sequencing of 16S, 18S and ITS amplicons for bacteria and archaea, protozoa and fungi, respectively) of the ruminal microbiome under different conditions ([Morgavi et al., 2015]; [Popova et al., 2019]; [Ramayo-Caldas et al., 2019]). Although these studies are of great interest, the interpretation of data generated by different studies remains a challenge because of contradictory results potentially related to differences in the methods used. Efforts are being made to standardize this type of analysis ([Pollock et al., 2018]). The major disadvantage of metataxonomics is the impossibility of accessing microbial function, despite the development of software for predicting functions from 16S rDNA sequences ([Langille et al., 2013]). Only metagenomics makes it possible to identify the genes present and the associated potential functions. Metagenomics applied to the rumen microbiota first led to the discovery of new biomass-degrading enzymes (Hess et al., 2011). Then metataxonomics and metagenomics were applied to the study of many other aspects: methane emission; effects of genetics, including breed and host species; and feed and feed additives on the composition of the rumen microbiome ([Auffret et al., 2017]). Another major advance made possible by metagenomics is the reconstruction of genomes of unknown species from metagenomic sequences. For example, in cattle, the genomes of 4,941 rumen bacteria have been assembled from metagenomes ([Stewart et al., 2019]). Although metagenomics provides information on the diversity and functional capacity within a microbiome (see figure 2), metatranscriptomics enables taking a further step towards understanding its functioning by providing a global view of the transcripted genes ([Li et al., 2019]a). This approach is limited by the difficulty of extracting good quality RNA and the extremely short life span of mRNA. Those constraints can be overcome by studying the metaproteome, which makes possible the identification of the proteins that are synthesized ([Honan and Greenwood, 2020]). Metabolomics provides access to primary or secondary metabolites, which are closely linked to the composition and functioning of the microbial ecosystem, and completes the -omic approaches ([Morgavi et al., 2015]).

1.2. Ruminal microbiota

The rumen contains an extremely dense and diverse population of microbes that includes the 3 domains of life (bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes) as well as viruses (mainly phages). Bacteria are predominant (1010–1011 cells per g of ruminal content) and encompass most of the metabolic functions in the rumen. Eukaryotes include protozoa (106 cells per g of ruminal content), which account for 30–50% of rumen microbial biomass, and fungi (105 zoospores per g of ruminal content). Bacteria, protozoa and fungi degrade and ferment ingested feed and convert it into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and CO2. Archaea (106–109 cells per g of ruminal content) are essentially methanogenic and mainly use CO2 and H2 produced by other microbes to synthesize methane. Rumen microorganisms have developed various interactions between them to ensure the efficient functioning of the trophic chain and allow microbial transformation of plant components into useful products for the host animal (mainly SCFAs and microbial proteins, but also vitamins).

More than 5,000 bacterial species are estimated to be in the rumen ([Kim et al., 2011]), and the majority have no cultivated representatives. Most of these bacterial species (around 80% of sequences) belong to the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. By comparing the bacterial phylogeny in more than 700 samples from 32 ruminant species from 35 countries, [Henderson et al. (2015)] identified ubiquitous bacterial groups that represented 67% of all detected sequences: Prevotella, Butyrivibrio, Ruminococcus and the non-classified Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Bacteroidales and Clostridiales. Their proportions also vary according to the fraction under consideration: free in the liquid phase, attached to food particles or attached to the ruminal epithelium. Using classical morphological criteria, more than 25 genera of protozoa have been identified in the rumen ([Williams and Coleman, 1997]); 18 genera of anaerobic fungi (phylum Neocallimastigomycota, order Neocallimastigales) have been described, but this number could be further extended because metataxonomic analyses have identified additional clades ([Edwards et al., 2017]; [Hess et al., 2020]). The total number of rumen eukaryotic genera and species is probably still underestimated. The diversity of rumen methanogenic archaea is limited to 4 orders, with the most common species belonging to the genera Methanobrevibacter and Methanoshaera ([Morgavi et al., 2010]), and is highly conserved among the 32 ruminant species studied ([Henderson et al., 2015]). The phages (estimates of up to 109–1010 per ml of ruminal content) have different morphotypes and belong mostly to the families Siphoviridae, Myoviridae and Podoviridae (Caudoviridae order). They probably play a role in the dynamics of bacterial populations through their lysis activity, thus participating in the recycling of nutrients (proteins and DNA) and enabling the transfer of genetic material ([Gilbert et al., 2020]).

1.3. Intestinal microbiota

Microbial fermentation also takes place in the intestinal compartments of the ruminant, especially in the caecum and colon. Substrates that have escaped ruminal degradation and duodenal enzymatic digestion, especially parietal carbohydrates and starch, are fermented there ([Plaizier et al., 2018]). A highly diverse microbiota is present throughout the intestines, but its composition varies according to the segment considered and between the lumen and the mucosa. Physiological differences in pH, the abundant presence of mucus and its composition lead to a specific microbiota in each intestinal compartment ([Plaizier et al., 2018]). Few studies have yet compared the taxonomic composition of the jejunum, ileum, cecum, colon and rectum in cattle, and most of the work has focused on feces, which are easier to obtain. In addition, most of these studies focus on the colonization of the intestinal microbiota of young calves, which is essential to their health ([Malmuthuge et al., 2015]). The richness and diversity of microbial populations in the distal part of the digestive tract are lower compared with those in the rumen, with the greatest intestinal bacterial diversity in the colon ([Lopes et al., 2019]). Variations in the microbial composition of the different intestinal compartments are mainly the result of physicochemical conditions (pH, redox potential and oxygen), availability of nutrients and adhesion sites, mucin secretions and exposure of the intestine to exogenous compounds ([Carbonero et al., 2014]).

Like the rumen, the majority of intestinal bacterial phyla are Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, with a particular abundance of Firmicutes ([Mao et al., 2015]). Sequences affiliated with bacteria associated with the degradation of parietal carbohydrates (mainly represented by the Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae families) are found throughout the digestive tract ([Lopes et al., 2019]). Methanogenic archaea and anaerobic fungi are also present. The mucosal community differs from the luminal community. For example, for the calf ileum, Firmicutes dominates the lumen, and Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria are present in the mucosa, including genera specific to this region ([Malmuthuge et al., 2014]). Those differences are also found in adults ([Mao et al., 2015]).

At the fecal level, metataxonomic metanalysis of bovine samples found the methanogenic genera Methanobrevibacter and Methanosphaera in more than 99% of samples and a prevalence of the bacterial genera Prevotella (Bacteroidetes) and Ruminococcus ([Holman and Gzyl, 2019]). Alistipes, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium and Escherichia/Shigella were also associated with feces. The fecal microbiota has the advantage of being easily accessible, but it does not specifically represent either the microbiota of the intestine or that of the entire digestive tract.

As with the rumen, the structure of intestinal (and fecal) communities varies from one study to another as well as from one individual to another. Different factors, such as diet or animal age, strongly influence study results ([Holman and Gzyl, 2019]).

1.4. Microbiota of udder skin

Over the last decade, the microbiota of the teat skin of dairy cows has been the subject of numerous studies ([Verdier-Metz et al., 2012]; [Doyle et al., 2017]; [Frétin et al., 2018]; [Andrews et al., 2019]), with culture-dependent methods combined with DNA sequencing approaches. That microbiota now is considered to be a major reservoir for the microbial diversity in raw milk ([Doyle et al., 2017]) as many of the genera detected in raw milk are also present on the teat skin. However, most of these studies deal with the contemporary dairy cow, which has its teats coated with broad-spectrum antiseptics at each milking (at least after milking, and often before). This is not the case for goats and especially not for sheep.

The ecosystem of the udder skin is made up of numerous microorganisms (bacteria, viruses and fungi, including yeasts and molds). Most are commensals or saprophytes, and some are pathogenic (for ruminants or humans). Nearly a hundred or so bacterial genera have been identified. Although coagulase-negative species of the Staphylococcus genus are widely represented, the most frequently identified genera include gram-positive bacteria such as Corynebacterium, Aerococcus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Turicibacter, Trichococcus, Eremococcus and Bifidobacterium. Gram-negative bacteria are also present: Romboutsia, Proteiniphilum and Psychrobacter. Only Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, Aerococcus, Enterococcus and Streptococcus are potentially pathogenic to the udder. Many of these bacteria, such as Aerococcus, Streptococcus, Bifidobacterium and Corynebacterium, are commonly found in milk and dairy products. Some are thought to originate in the intestinal tract of animals (Bifidobacterium or Proteiniphilum), whereas others (Rhizobium, Xanthomonas, Variovorax, Devosia and Stenotrophomonas) are usually found in soil ([Doyle et al., 2017]). The fungal community of the teat skin is still relatively unstudied. According to [Andrews et al. (2019)], Debaryomyces prosopidis appears to be the most abundant species and was observed in 69% of samples analyzed by amplification of the ITS1 region of rRNA. Other common genera identified include Cryptococcus, Caecomyces, Penicillium and Rhodotorula.

Each of the microbiotas hosted by the animal has specific traits in terms of taxonomic composition and functionality. However, the composition and intrinsic properties of those microbiotas and the way they interact with each other and with their host vary according to many cross-cutting factors, particularly the environment (including diet) and host genetics.

2. Main factors in microbiota variation

Digestive microbiotas are mainly affected by diet, genetics and animal age. The microbiota of the teat skin of dairy cows is a crossroads for microbial transfer between the different farm environments and the milk. It is affected by the milking process, including the nature of the active ingredients applied to the teats at the time of milking, and by the general environmental conditions on the farm.

2.1. Environment

Forage, pasture, bedding, dung, airborne microorganisms in buildings, water, milking machine and associated practices are all potential sources of microorganisms that can contaminate an animal’s teat (skin or canal) and milk or affect the digestive microbiota.

The housing condition of an animal seem to play a central role in the microbial composition of the teat skin. Differences in the bacterial diversity of milk, feces and teat surface samples have been found to occur based on whether the animals were housed or grazed ([Doyle et al., 2017]). Other factors related to animal housing, such as bedding type and season, should be considered. The influence of bedding type on teat surface microbial load has been demonstrated ([Rowbotham and Ruegg, 2016]; [Guarín et al., 2017]), as well as the greater diversity of microbial profiles of the teat apex collected during winter compared with summer ([Derakhshani et al., 2018]). In addition, although the microbial populations identified in the cistern milk of primiparous cows housed on new or recycled sand appear comparable, they differ from those of animals housed on sawdust or manure ([Metzger et al., 2018]). As microbial sources that can lead to accidental contamination with pathogenic bacteria are numerous, milking practices are often chosen to eliminate them without considering potential reservoirs of beneficial microorganisms ([Rowbotham and Ruegg, 2016]). The application of drastic hygiene procedures (pre- or post-milking teat cleaning with or without teat disinfection, cleaning and decontamination of the milking machine) can reduce microbial levels on the teat skin by 2.6 log (cfu/ml) ([Rowbotham and Ruegg, 2016]; [Guarín et al., 2017]). In particular, intensive milking hygiene is reported to be associated with lower levels of gram-positive, catalase-positive bacteria and yeasts ([Monsallier et al., 2012]). Other practices, such as single or robotic milking as well as intramammary antibiotic therapy and external or even internal teat fillers, could also be associated with qualitative or quantitative changes in some commensal or opportunistic microbes in the teat skin and consequently in the milk.

2.2. Composition of adult ration

Diet is the most important factor for variation in the ruminal microbiota ([Malmuthuge and Guan, 2017]). Diet also modifies the intestinal microbiota.

In animal husbandry, the ration element with the greatest effect on microbiota variation is the ratio of forages to concentrates. Dairy cows frequently are fed a diet rich in cereals to meet their high energy requirements. Generally, in the rumen, an increase is observed for amylolytic bacteria (e.g., Streptococcus bovis, Ruminobacter amylophilus) with diets rich in concentrates and for fibrolytic bacteria (e.g., Fibrobacter succinogenes, Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens) with diets rich in forage. Response varies within these 2 major functional groups of bacteria depending on the nature of the forage and concentrates. For example, in the rumen, a diet rich in starch may be associated with a significant increase in the Lactobacillus population ([Zened et al., 2013]). More generally, the main effect of a diet rich in cereals is a decrease in bacterial diversity as well as a marked decrease in protozoan and fungal populations ([Ishaq et al., 2017]). The microbiota of the large intestine is also modified by cereal-rich diets ([Plaizier et al., 2017]). In some cases, this type of ration causes ruminal and intestinal acidosis, which alters the functionalty of the digestive microbiota, reduces the use of nutrients in the ration and can sometimes trigger inflammatory responses ([Plaizier et al., 2008]). In addition to inflammatory phenomena, this type of ration favors certain bacteria pathogenic to the udder ([Zhang et al., 2015]) and may directly or indirectly modify the microbiota of the udder skin. Furthermore, [Frétin et al. (2018)] have demonstrated differences in the abundance of bacterial taxa (grouping of bacteria on the basis of their phylogenetic relationships) on the surface of the teats of dairy cows depending on whether grazing was done with or without added concentrates. The genus Clostridium, which is more abundant on the teats of animals in semi-extensive systems, could come from feces and be promoted by the distribution of concentrates.

The second major factor for variation in the ruminal microbiota and its activity is the polyunsaturated fatty acids present in forages or concentrates, which are potentially toxic for some bacteria ([Enjalbert et al., 2017]). In addition, the effect of unsaturated fatty acids depends on the starch content of the diet ([Zened et al., 2013]).

Probiotics are also capable of modifying the ruminal and intestinal microbiotas. The most studied probiotics in ruminants are yeasts. These can favor certain populations of bacteria, fungi and protozoa ([Ishaq et al., 2017]).

Finally, other substances of plant origin are potential modulators, but the efficacy and safety of many of them remain to be proven. However, tannins have proved to be quite effective ([Buccioni et al., 2017]; [Corrêa et al., 2020]).

2.3. Host genetics

In ruminants, the genetic control of the microbiota by the host is still rather poorly understood and much less detailed than for humans, for which links between host genetics, digestive microbiota and particularly health have been clearly established. Nevertheless, recent studies focused on the ruminal microbiota of cattle ([Li et al., 2019]b; [Wallace et al., 2019]; [Zhang et al., 2020]) and sheep ([Rowe et al., 2015]; [Marie-Etancelin et al., 2018]) report the existence of genetic control of microbial communities, whether in dairy or lactating animals. In sheep, [Rowe et al. (2015)] demonstrated the existence of a genetic determinism of the microbial community by synthesizing its variability using correspondence analysis. Estimates of heritability of abundances of bacterial taxa were then published; 22% of bacterial genera, 59 bacterial taxa or 39 operational taxonomic units (OTUs; i.e., grouping of 16S RNA sequences on the basis of their similarity) had significant heritabilities greater than 0.10, 0.15 or 0.20, respectively ([Marie-Etancelin et al., 2018]; [Li et al., 2019]; [Wallace et al., 2019]). Two of those studies report an independence between the level of abundance of the OTUs or taxa and their level of heritability; therefore, even OTUs with low abundance can be heritable. In contrast to phylum Bacteroidetes bacteria, which are highly affected by environmental factors, bacteria of the genus Ruminococcus seem to be strongly associated with host genetics ([Li et al., 2019]). The great diversity of these Ruminococcus and their host association patterns suggest the existence of co-evolutionary relationships between Ruminococcus and its host ([La Reau et al., 2016]). Furthermore, heritable OTUs seem to co-act with each other more than non-heritable OTUs and are largely related to ruminal fatty acids produced by ruminal fermentation, mainly acetate and propionate ([Wallace et al., 2019]).

The existence of a genetic determinism of diversity indices seems controversial. Only one analysis of a genome-wide association between markers of the host genome and the abundance of rumen microbial taxa has been published ([Li et al., 2019]). Nineteen QTLs located on 12 bovine chromosomes were associated with 14 bacterial taxa, 12 of which had been identified as heritable; neither diversity indices nor archaea abundances showed QTLs. As proposed by [Difford et al. (2018)], simultaneous consideration of the contributions of the metagenome of the microbiota and the host genome is desirable in the analysis of variability for traits of interest in ruminants, because the microbiota itself is dependent on host genes. Subsequent studies ([Zhang et al., 2020]) have illustrated the usefulness of including both microbial and host genetic information to better understand complex traits.

2.4. Influence of dietary practices for young animals

In ruminants, the digestive tract is sterile, poorly developed and non-functional at birth, but it is quickly colonized and digestive functions are gradually established ([Fonty and Chaucheyras-Durand, 2007]). All studies on young ruminants agree that richness and diversity increase with age and that the microbiota becomes more mature and more stable over time ([Malmuthuge and Guan, 2017]). For example, the dynamics of the establishment of the ruminal microbiota in calves is linked to age and diet change and can be divided into 3 stages ([Rey et al., 2014]).

The first 2 to 3 days of life correspond to an initial phase of colonization by essentially facultative anaerobic bacteria (Proteobacteria more than 50%). These will play an important role in the establishment of the ruminal environment, particularly for strictly anaerobic populations ([Fonty and Chaucheyras-Durand, 2007]). [Gomez-Arango et al. (2017)] highlight the important role played by the mother in microbial inoculation through different matrices (vagina, feces, skin, saliva and colostrum).

The second phase comes after 3 days of life with the transition to artificial or maternal suckling. During this phase, a significant change in the bacterial community takes place. Strictly anaerobic bacteria dominate; the first archaea then settle and are followed by the first fungi at 10 days of age ([Fonty and Chaucheyras-Durand, 2007]). After the colostral phase, bacterial colonization is different from one individual to another. This is probably the result of a variable pioneer community that is set up from birth, preparing the ecosystem differently for the implantation of the anaerobic microbiota ([Jami et al., 2013]).

The last stage of colonization is between 14 days and weaning (70 days on average). It depends on solid food intake, age at weaning and the presence or absence of adult animals ([Rey et al., 2014]). Protozoa settle during this phase from 21 days of age ([Fonty and Chaucheyras-Durand, 2007]). Studies carried out on calves ([Meale et al., 2016]) and on kids ([Abecia et al., 2017]) fed a milk replacer show that the Bacteroides genus decreases sharply with the introduction of cereals into the diet. [Anderson et al. (1987)] showed that the introduction of solid feed in calves weaned at 4 weeks of age favored higher rumen microbial abundance compared with calves weaned at 6 weeks of age without the introduction of solid feed.

Therefore, in addition to the effect of diet, the age of an animal from birth until weaning has an important effect on the digestive microbiota. Controlling the microbiota and its implantation in the digestive tract just after the birth of an animal could be a way of programming the microbiota and orienting it ([Malmuthuge and Guan, 2017]).

3. Main links with traits of interest to breeders

Concentrate-rich diets cause a significant change in microbiotas and potentially lead to altered feed efficiency, animal welfare and health (acidosis). Along with acidosis, other digestive disorders (diarrhea of infectious or non-infectious origin) or even extra-digestive disorders (lameness) may be linked to altered microbial balance (or dysbiosis) within the digestive tract. Any intestinal dysbiosis may influence the host’s susceptibility to infection ([Malmuthuge and Guan, 2017]). Finally, in addition to the close link between feed efficiency and digestive microbiotas, the latter influence the emission of pollutants to the environment and the quality of animal production.

3.1 Microbiotas and health

Dysbiosis caused by acidosis from diets rich in concentrates is characterized by a decrease in the richness and diversity of the ruminal and even intestinal microbiotas ([Mao et al., 2013]; [Khafipour et al., 2016]). The abundance of taxa with a beneficial effect for the host is reduced, and the abundance of bacteria with an unfavorable or even pathogenic effect is increased ([Plaizier et al., 2018]). Several studies report that with a concentrate-rich ration, the relative abundance of Firmicutes increases to the detriment of Bacteroidetes ([Mao et al., 2013]; [Plaizier et al., 2017]), which would not be favorable functionally ([El Kaoutari et al., 2013]). However, as with humans ([Mondot and Lepage, 2016]), the significance of the ratio between Firmicutes and Bacteriodetes for diagnosing health problems requires further study. Furthermore, in some studies ([Li et al., 2011]; [Plaizier et al., 2017]), an increase in certain potentially pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli that trigger an inflammatory response in these ruminal conditions has been observed ([Khafipour et al., 2011]). The effects of acidosis on the composition of the microbiota differ between studies and even between cows within the same study. [Zaneveld et al. (2008)] explain these differences by a permanent co-evolution of the host and the microbiota. Different strategies to prevent acidosis have been tested and seem promising. Most of them consist of increasing the proportion of parietal carbohydrates in the diet to favor the fibrolytic community, but also adding food supplements and additives such as buffers and probiotics ([Plaizier et al., 2018]). Finally, a diet rich in concentrates would be associated with a higher proportion in milk of certain opportunistic bacteria such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Streptococcus parauberis and Brevundimonas diminuta ([Zhang et al., 2015]).

Newborn calves are frequently infected with various enteric pathogens that lead to diarrhea of varying severity and cause significant economic losses ([Cho and Yoon, 2014]). However, at the intestinal level, dysbiosis and diarrhea or the presence of pathogens are strongly linked. For example, newborn calves infected with cryptosporidia have a fecal microbiota enriched with Fusobacterium ([Ichikawa-Seki et al., 2019]). Similarly, in feedlot calves, hemorrhagic diarrhea is associated with dysbiosis of the fecal microbiota ([Zeineldin et al., 2018]). In these examples, whether the observed dysbiosis is the cause or consequence of the disease cannot be determined. However, an increase in Proteobacteria, particularly Enterobacteriaceae, in the fecal microbiota also appears to be the signature of various diseases and diarrhea conditions in humans and monogastric animals ([Shin et al., 2015]). Nutritional strategies that do not use antibiotics have been developed to combat enteric diseases, particularly the use of probiotics to orient the intestinal microbiota for the benefit of animal health ([Plaizier et al., 2018]).

The ruminant microbiota is also linked to the risk of mastitis. For example, type of bedding appears to affect the exposure of teat skin to mastitis-associated pathogenic microorganisms ([Rowbotham and Ruegg, 2016]). In addition, recent studies ([Falentin et al., 2016]; [Derakhshani et al., 2020]) have shown that the bacterial community in the teat canal of dairy cattle varies according to the animal's history of mastitis: healthy quarters had different taxonomic profiles from those that had already developed mastitis. However, for clinical mastitis, the use of antibiotic therapy, particularly local antibiotics, may contribute to the selection of resistant bacteria present in the teat canal or modify bacterial diversity. In addition, subclinical ovine mastitis seems to be associated with a significant increase in milk of certain common microbial genera of the mammary gland and a concomitant reduction in its microbial diversity ([Esteban-Blanco et al., 2020]). The comparison of dairy ewes from different lines selected for susceptibility to mastitis showed a significant increase in the abundance of 4 genera of ruminal bacteria (Olsenella, Prevotella 1, Prevotellaceaea Ga6a1, and Syntrophococcus) in the animals most susceptible to mammary infections ([Marie-Etancelin et al., 2018]).

Mammary pathology in general and mastitis in particular have a major effect on animal welfare. Indeed, mastitis is the most common disease in dairy farming for the three most common ruminant species (cattle, sheep and goats), particularly for cows. In addition, some mammary infections, which vary according to the host species, are the cause of acute to over-acute clinical cases.

3.2 Microbiotas and the environment

The livestock sector is a major source of greenhouse gases (GHG) worldwide. This sector emits about 14.5% of total global anthropogenic GHG emissions ([Gerber et al., 2013]), and enteric methane (mainly from rumen origin) accounts for 44%. A natural co-product, CH4 results from the microbial degradation of feed in the rumen and allows the recycling of hydrogen produced by fermentation. This phenomenon is essential because the accumulation of hydrogen would have negative effects on fermentation.

Several strategies have used to try to reduce rumen methane production ([Martin et al., 2010]; [Morgavi et al., 2010]; [Huws et al., 2018]). Most are not widely used because of low efficiency, poor selectivity, toxicity of chemicals to animals or the development of microbial resistance to anti-methanogenic compounds. Some of these approaches target H2 metabolism by decreasing H2 producers such as protozoa, but very few focus on increasing H2 consumption pathways other than methanogenesis.

[Rowe et al. (2015)] report significant genetic correlations between ruminal microbial communities and methane emissions. [Ramayo-Caldas et al. (2019)] identified a ruminotype of 86 OTUs associated with increased methane emissions. Those OTUs explain 24% of the phenotypic variance in the amount of methane produced, whereas the contribution of the host genome is estimated at 14%.

In addition, nitrogen losses in ruminant feces and urine can account for up to 90% of the nitrogen consumed by the animal, which poses a problem in terms of ration balance but also environmentally in some production regions (Dijkstra et al., 2013). Those losses are linked to the high proteolytic activity of rumen microbes that produce ammonia, which is not totally reused for the synthesis of microbial proteins and is then excreted by the animal, thus modulating the digestibility and metabolic use of nitrogen. Feed diets that follow recommendations based on an animal’s physiology are the best solution to reduce nitrogen rejection.

Finally, the ruminal microbiota produces phytases that enable phosphorus of plant origin to be used efficiently and thus limits its content in ruminant excrement.

3.3 Microbiotas and food efficiency

The ruminal microbiota is strongly related to animal performance and intake and is thought to contribute to many phenotypes ([Xue et al., 2018]). Predictive models that include the ruminal microbiota have been proposed for those traits [Gleason and White, 2018]).

The ruminal microbiota is highly dependent on the quantity of dry matter intake and on animal feed efficiency (Delgado et al., 2019). For example, the genus Prevotella has a higher relative abundance in the rumen of the most efficient dairy cows. Nevertheless, the abundance of this genus is only weakly correlated with the feed efficiency parameters measured in their study. Thus, [Malmuthuge and Guan (2017)] reported in their review that the relationships between the ruminal microbiota on the one hand and milk production and feed efficiency on the other hand are still uncertain because many studies contradict each other. For example, the genus Prevotella can be negatively or positively correlated with those 2 parameters. One possible reason for the differences is that most sample sizes were small. Another reason is the multiplicity of statistical approaches, some of which are unsuitable for the microbial count data.

Using data from more than 700 cattle, [Li et al. (2019)] showed that most microbial taxa identified as heritable contribute strongly to explaining variations in feed conversion and dry matter intake, but little or no variation in the composite criterion of residual feed consumption. Using a metagenomic approach, [Roehe et al. (2016)] reported that the relative abundances of 49 rumen microbial genes had to be taken into account to predict 85% of the variation in the feed conversion rate. The metagenomic approach implemented by [Roehe et al. (2016)] is of interest because of its connection to functional aspects of the microbiota rather than the metataxonomic approach used by [Li et al. (2019)]. However, only a small number of animals can be studied (n = 8) because of procedural cost, which limits the applicability of the conclusions and makes the results incompatible with large-scale genetic approaches.

3.4. Microbiotas and product quality

The microbiota can influence different factors of a product's quality: organoleptic, technological, sanitary and nutritional. The most widely studied product has been milk. A recent study ([Carafa et al., 2020]) has shown that the microbial levels of alpine pasture milk are significantly higher than those of milk from permanent lowland meadows. Numerous strains belonging to species well known for their technological or probiotic activities were isolated from alpine milk (20% Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis/cremoris, 18% Lactobacillus paracasei, 14% Bifidobacterium crudilactis and 18% Propionibacterium sp.), which compares with 16, 6, 2 and 5%, respectively, for lowland milk. In addition, mountain milk showed a significant reduction in Pseudomonas and an increase in the genera Lactococcus, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. Similarly, the grazing system (exclusive grazing vs. grazing plus concentrates) of dairy cows is associated via the teat with the microbiota of the milk and the cheese (Frétin et al., 2018); 85% of OTUs in raw milk and 27% of those in ripened cheese were found on the teat skin.

The routes and factors of dissemination of food-borne pathogens from the animal and its environment to the milk have been the subject of numerous studies. The udder (teat surface, gland) is considered as a reservoir of pathogens (S. aureus; [Rainard et al., 2018]) or a vector of them (shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli; [Frémaux et al., 2006]; and Listeria monocytogenes; [Castro et al., 2018]). However, few studies explore factors that affect the balance between commensal microbiotas and pathogens for the consumer. [Monsallier et al. (2012)] have shown that certain practices, such as the use of straw bedding and moderate milking hygiene (cleaning the teat before milking instead of systematic disinfection), tend to reduce pathogens and preserve microbial populations of technological interest.

Finally, the fatty acid profile of milk, which modulates the texture and nutritional properties of milk fats, is highly dependent on the phenomenon of biohydrogenation by ruminal bacteria ([Enjalbert et al., 2017]). For example, when the trans-11 biohydrogenation pathway is inhibited in the rumen, both rumenic and vaccenic acids decrease in cow's milk ([Kaleem et al., 2018]). However, those fatty acids would present interesting properties for the human consumer ([Troegeler-Meynadier and Enjalbert, 2005]), which also applies to meat.

Conclusion

Ruminant microbiotas are composed of bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes and viruses. Bacteria are the most numerous and the most involved in the biological roles of microbiomes; they are also the most studied. Archaea are mainly involved in methanogenesis in the digestive tract. Eukaryotes are in the minority, but their exact role still is little known and their importance within ecosystems remains to be clarified. Extremely little is known about ruminant viruses. At present, studies of the effects of microbiotas on their host focus almost exclusively on the relationship with animal health and, for digestive microbiotas, production performance and feed efficiency. This review also highlights the importance of environmental and other factors of potential use in animal husbandry: feed, hygiene practices, animal management, genetics and age. Those factors interact in livestock farming, and a global approach must be developed to offer livestock farmers integrated solutions.